>Corresponding Author : Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos

>Article Type : Research Article

>Volume : 4 | Issue : 1

>Received Date : 18 Jan, 2024

>Accepted Date : 31 Jan, 2024

>Published Date : 04 Feb, 2024

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JDOE2400102

>Citation : Chrysanthakopoulos NA and Vryzaki E. (2024) Investigation of Periodontal Condition, and Tooth Loss in Multiple Myeloma Patients: A Case-Control Study. J Dent Oral Epidemiol 4(1): doi https://doi.org/JDOE2400102

>Copyright : © 2024 Chrysanthakopoulos NA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Research Article | Open Access | Full Text

1Dental Surgeon, Oncologist, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, PhD in Oncology(cand), Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

2Department of Dermatology, Rio University Hospital of Patras, Consultant in Dentistry, NHS, Athens, Greece

*Corresponding author: Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, PhD in Oncology(cand), Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Abstract

Objectives: Studies have long suggested a link between Periodontal Disease and an increased risk of other inflammatory diseases, and diverse types of cancer. The aim of the current research was to investigate the possible differences regarding the periodontal condition and tooth loss between individuals suffering from Multiple Myeloma (MM) and healthy ones.

Methods: This was a population-based retrospective case-control study in which 98 MM patients and 196 matching healthy controls were interviewed and dental and oral clinically examined. The clinical indices used to define the periodontal condition for MM patients and healthy individuals concerned Probing Pocket Depth (PPD), Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL), Plaque Index (PlI), Gingival Index (GI), and number of missing teeth. Univariate and logistic regression models were carried out to assess the data analyzed.

Results: Individuals with increased BMI (p=0.003, 95% CI= 2.405) who suffered from MM and those with a family history of MM (p=0.000, 95% CI=8.495), were statistically significantly different compared with the healthy ones. Moreover, GI (p=0.042, 95% CI=2.451), was statistically significantly different between MM patients and the healthy individuals after controlling for smoking and socio-economic status.

Conclusion: GI was statistically significantly different between individuals who were suffered from MM and healthy individuals.

Keywords: Multiple Myeloma; Periodontal Disease; Adults; Risk Factors

Abbreviations: MM: Multiple Myeloma, PPD: Probing Pocket Depth, CAL: Clinical Attachment Loss, Pli: Plaque Index, GI: Gingival Index, CRAB: Calcemia Renal insufficiency Anemia and Bone lesions, MGUS: Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance, PD: Periodontal Disease, CI: Confidence Interval, BMI: Body Mass Index, BOP: Bleeding on Probing, OR: Odds Ratios, GBI: Gingival Bleeding Index

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is one of the most common hematological malignancies of unknown etiology [1], however possible risk factors concern advanced age, family history, obesity, certain chemicals, and radiation exposure [2-4]. An increased risk of MM in certain occupations has also been recorded [5]. This is due to the occupational exposure to aromatic hydrocarbon solvents having a role in pathogenesis of MM [6].

MM as a malignant tumor has been classified by WHO as a non-Hodgkin lymphoma derived from B lymphocytes. It is characterized by the development of a plasma cells clone producing monoclonal immuno-globulins or their fragments that infiltrate the bone marrow thus destructing the bone structure, in the skull and in periodontal tissues. This obstructs the appropriate blood cells components production. MM accounts for 1% of all cancers and is the second leading hematologic malignancy after lymphoma [7], affects 4-5/100,000 individuals per year and its frequency increases with age. The median age of diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years, with a higher prevalence in males, as it is 1.5 times more frequent in males than females [8]. The prognosis of MM varies according to age and is worse in individuals over 65 years when compared to younger ones [7,9].

Approximately 80% of diagnosed MM is preceded by an asymptomatic premalignant stage known as Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS) [10]. MM classical type is characterized by clinical signs such as hyper Calcemia, Renal insufficiency, Anemia, and Bone lesions (CRAB) [11]. The main clinical signs/symptoms of MM are bone pain, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure, which can arise from the disease itself or from its treatment, accompanied or not by pathologic fractures, infections, fatigue, and secondary amyloidosis [12].

Commonly, bone lesions concern diffuse or localized osteolytic lesions, as plasmacytomas, or by a ‘punched-out’ pattern [1]. The mandibular and maxillary bones may be affected by osteolytic lesions [1,13-22] and 35% of individuals diagnosed with symptomatic MM present lesions in the mentioned bones [23].

The clinical manifestations of MM can be recognized at early stages [13]. Some clinical signs/symptoms of MM may display in the oral tissues and dentists should be able to detect lesions that may represent MM oral manifestations during the routine oral clinical and radiographic examinations. The primary clinical signs/symptoms of the disease will be detected in the oral cavity in 14% of MM individuals [14,24]. MM maxillofacial manifestations appear more frequently in the mandible than in the maxilla with an incidence of 8-15% [12,16,21,25] and they include soft tissue amyloid deposits [26], external dental root resorption [22], pain, bleeding, gingival enlargement, osteolytic lesions, dysphagia, swelling, tooth loosening, hypesthetic or anesthetic sensation of the lower lip (Vicent symptom), and amyloidosis with macroglossia [13,20,27].

However, the international literature on the MM oral manifestations is restricted and mainly concerns case reports [12,14,18,21].

MM patients frequently suffer from Periodontal Disease (PD) progression , that initially leads to gingival bleeding and later to pathological loosening of teeth, atrophy of bone support and of surrounding periodontal tissues, and eventually tooth loss. Those pathological clinical signs/symptoms are accompanied by pathological conditions in the oral mucosa and especially in the tongue [28,29].

PD, gingivitis and mainly periodontitis is the most frequent destructive and progressive disease of periodontal tissue structures worldwide [30]. PD may have systemic effects in diverse organs such as heart, lungs, etc., as several reports have recorded significant associations between PD and systemic diseases and disorders, such as cardiovascular (CVD) and atherosclerotic disease, respiratory diseases such as COPD, diabetes mellitus, cancer, etc. [31].

The possible role of PD as a risk factor in cancer development has also been investigated by several researchers in organs such as oral cavity, oesophagus, stomach, lungs, pancreas [32-36] with controversial results, even after controlling for potential confounders such as smoking status, socio-economic level, etc. In contrast to the mentioned articles, few reports have investigated the oral conditions or periodontal status in individuals who suffered from MM or other types of cancer, such as gastric and lung cancer [37,38]. A literature review by Epstein et al. [16] reported 14.1% of the patients with MM presenting some type of oral lesions. A retrospective study [15] reported mandible lesions occurring in 15.6% and oral mucosa lesions affecting 2.6% of them.

The prevalence of caries and the periodontal condition in individuals with MM have not been reported in full articles in the international literature. It is important to highlight that chronic oral diseases and poor oral hygiene may develop into acute oral infections and potentially life threatening systemic conditions in immunosuppressed patients [39]. The current research was carried out to investigate the possible differences in periodontal condition and tooth loss between individuals who suffered from MM and healthy ones.

Materials And Methods

Research design and study sample

Study size assessment was based on MM prevalence [40] and the EPITOOLS guidelines (https://epitools.ausvet.com.au) determined with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and desired power 0.8. The study sample comprised of 294 individuals, 168 males and 126 females aged 65-85 years which were selected from three private practices, two medical and a dental one between March 2021 and August 2023. 98 individuals suffered from MM-cases and 196 were healthy individuals-controls. Cases and controls filled in a medical and a dental health questionnaire and were clinically examined regarding their periodontal condition and the number of missing teeth.

Cases and Controls Eligibility Criteria

To be eligible, individuals who suffered from MM and healthy ones should not have been treated by a conservative or a surgical treatment in their oral tissues in the last 6 months, or prescribed for systemic glucocorticoids or immuno-suppression agents or antibiotics within the same time period. They should also have more than 15 teeth and periodontitis from stage I to IV [41].

Participants who suffered from CVD, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, acute pulmonary diseases or any other type of malignancies were excluded from the study protocol as those diseases could potentially affect oral and periodontal tissues [42] and could lead to biased secondary associations. For that reason MM patients and healthy individuals, were selected from the same city population in order to avoid or eliminate possible selection biases. To avoid such biases the selection of healthy individuals was based on MM patients’ environment, such as friends, colleagues, etc., and cases and controls were matched regarding their gender, age, socio-economic and smoking status.

Cases group consisted of individuals whose the MM primary diagnosis was based on patients’ medical files, however the definitive diagnosis was confirmed by the Diagnostic criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group [43], and concerned individuals with symptomatic MM (Proportion of plasma cells in bone marrow: ≥ 10%, M protein in serum: Detectable in serum and/or urine, and End-organ damage (CRAB criteria: hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, bone lesions): present. Individuals with monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS) and those with Smoldering Myeloma were excluded from the study protocol.

No oral hygiene instructions was given to MM patients group for a period of two weeks after the definitive diagnosis of MM and before the application of any medical treatment , i.e. targeted therapy, immunotherapy, corticosteroids and chemotherapy as improvement of oral hygiene could be affect the intra-examiner variance.

A randomly selected sample of 60(20%) individuals was clinically re-examined by a well-trained and calibrated Dental Surgeon after two weeks in order to assess the intra-examiner variance. After consideration of the ID’s of the double examined individuals no differences were recorded between both clinical examinations (Cohen's Kappa= 0.98).

The current case-control study was not an experimental one and was not reviewed and approved by authorized committees (Greek Dental Associations, Ministry of Health, etc). However, it was carried out in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Individuals who agreed to participate in the study design and protocol signed an informed consent form.

Data Collection and Intra-Oral Examination

MM patients and healthy individuals filled in a modified Medical Questionnaire [44] by Minnesota Dental School. The collected data concerned the medical/dental history and epidemiological parameters, such as age, gender, smoking status, educational and socio-economic status, etc.

Participants’ age was classified as 65-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80+, educational status as elementary level and graduated from University/College, socio-economic status as ≤ 1,000 and >1,000 €/ month, and cigarette smoking status was classified as never (individuals who smoked <100 cigarettes during their lifetime), and former (individuals who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and reported that they now smoke “not at all”)/current smokers (individuals who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life-time and reported they now smoke “every day” or “some days”). Body Mass Index (BMI) is an obesity index and was classified as normal (<30 Kg/m2) and high (≥30 Kg/m2), as is considered as a risk factor for MM development [45]. Similarly, alcohol consumption ≤ 12.5 gr per day was classified as light and >50gr per day was classified as moderate and heavy drinking [46].

The mentioned Dental Surgeon performed all periodontal examinations in a dental clinic using a Williams (with a controlled force of 0.2N (DB764R, Aesculap AG &Co. KG,) periodontal probe, mouth mirror, and dental light source. Third molars and remain roots were excluded from scoring. The oral and dental examination concerned the periodontal health status and included probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL), gingival index (GI), plaque index (PlI), and bleeding on probing (BOP). All PD indices were recorded at four sites per tooth (mesiolingual, mesiobuccal, distolingual, and distobuccal) in all quadrants and the worst values of the indices recorded to the nearest 1.0 mm, and coded as dichotomous variables. PPD was classified as 0-3.00 mm (absence of disease/mild disease) and ≥4.0 mm (moderate and severe disease) for mean PPD [47], CAL severity was classified as mild, 1-2.0 mm of attachment loss and moderate/severe, ≥3.0 mm of attachment loss [48]. Gingival inflammation severity was coded as follows: -score 0: normal situation of gingival tissue and/or mild gingival inflammation, that corresponds to Löe and Silness [49] classification as score 0 and 1, respectively, and -score 1: moderate/severe gingival inflammation that corresponds to the mentioned classification as score 2 and 3, respectively. PlI by Silness and Löe [50] was assessed by the same probe at the mentioned sites. The presence of dental plaque was determined whether it was visualized with naked eye or existed abundance of soft matter within the gingival pocket and/or on the tooth and gingival margin (score 2 and 3, respectively, according to PlI) and considered as present if at least one site showed the characteristic sign. The number of missing teeth was coded as none, 1-4, 5-10, >10 missing teeth [51], and the presence/absence of BOP was recorded and coded as dichotomous variables.

Statistical analysis

The univariate analysis model was performed to estimate the associations between the independent indices examined in MM patients and healthy individuals. Categorical data were shown as frequencies and percentages. Unadjusted Odds Ratios (OR's) and 95% (Confidence Interval) CI were also assessed. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to examine the associations between MM as a dependent variable and the independent ones that were determined by the enter method. Adjusted OR's and 95% CI were also assessed. Finally, the independent variables were included to stepwise method in order to estimate gradually the indices that showed significant differences with the dependent one. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS statistical package (SPSS PC20.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,USA), and a p value less than 5%(p< 0.05) was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

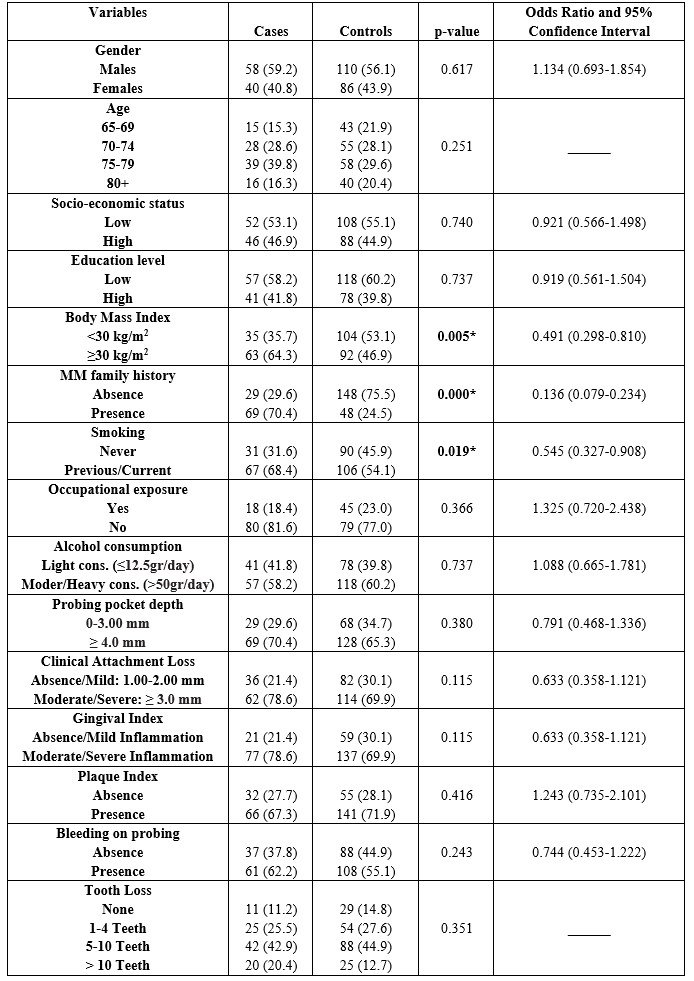

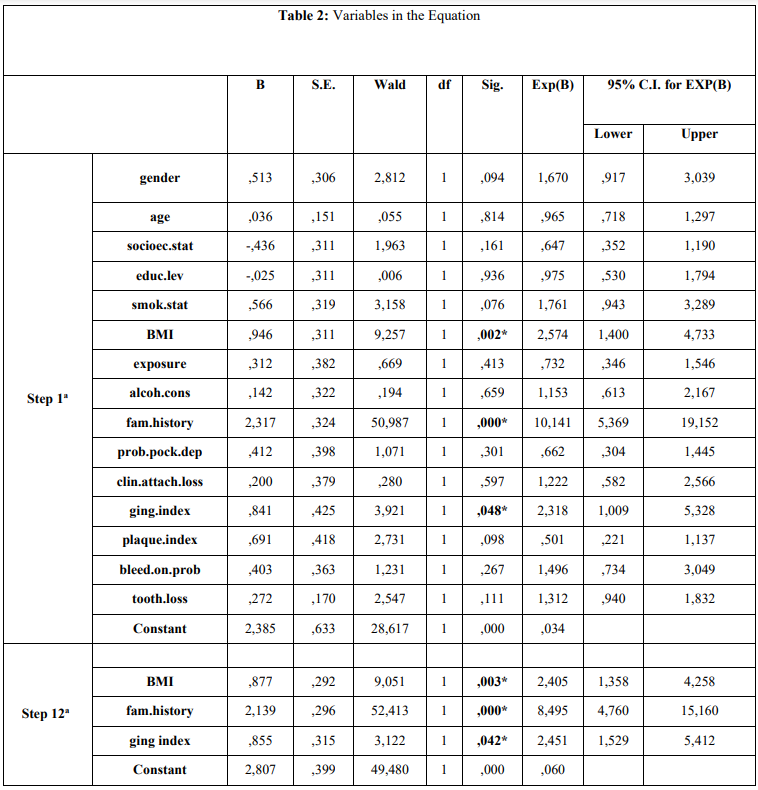

Cases and controls showed a mean age of 73.2 years (± 4.38). Univariate analysis is presented in Table 1 and showed that increased BMI (p=0,005), MM family history (p=0.000) and smoking (p=0.019) were found to be statistically significantly different between MM patients and healthy individuals. According to the step 1a of the regression model, the main finding was that increased BMI (p=0.002), MM family history (p=0.000), and gingival inflammation (GI) (p=0.048) were significantly different between cases and controls (Table 2). The final step (12a) showed the same indices to be significantly different between cases and controls, increased BMI (p=0.003), MM family history (p=0.000), and gingival inflammation (GI) (p=0.042).

Table 1: Univariate analysis of cases and controls regarding each independent variable examined

* p-value: statistically significant

Table 2. Presentation of association between independent variables and GBM cancer according to Enter (first step) and Wald (final step) method of multiple logistic regression analysis model.

a. Variable(s) entered on step 1: gender, age, socioec.stat, educ.lev, smok.stat, BMI, exposure, alcoh.cons, fam.history, prob.pock.dep, clin.attach.loss, ging.index, plaque.index, bleed.on.prob, tooth.loss.

* p-value: statistically significant

Discussion

MM is a malignant tumor classified by WHO as a non-Hodgkin lymphoma derived from B lymphocytes, as already mentioned. It is characterized by the development of a plasma cells clone synthesizing monoclonal immuno-globulins or their fragments that infiltrate the bone marrow and destroy the bone structure, in facial parts of the skull and in periodontal tissues, and obstructs the production of peripheral blood components [28]. Many studies showed that oral lesions were the first detected sign of MM [1,12-14,16-20,52-55], as maxilla and mandible can be affected, and patients may present with pain, bony swelling, epulis formation, or sudden tooth or teeth movement [17,37]. Oral lesions can also be the first sign of MM progression or recurrence [24]. The maxillary pain is highly suggestive of the disease [14], whereas MM patients may have oral manifestations of periodontitis and it is necessary to rule out any differential diagnosis [21]. Moreover, MM patients frequently suffer from PD progression which, at the initiation, results in gingiva bleeding and later in pathological loosening of teeth, atrophy of bone support and of surrounding periodontal tissues, and eventually tooth loss.

Those conditions are accompanied by other pathological symptoms/ signs in the mucosa and especially in the tongue [29]. Most of the oral conditions found in patients with MM are not specific, therefore the differential diagnosis with other oral conditions and with manifestations of systemic diseases is important.

The results of the current survey showed statistically significant differences between cases and controls, regarding increased BMI, a family history of MM, and gingival inflammation expressed by GI. It was also observed no statistically significant difference between the groups examined in regard to epidemiological parameters of advanced age, gender, educational, and socio-economic level, smoking status, exposure to chemical agents, and light/moderate-heavy alcohol consumption, variables that have been considered as possible risk factors for MM development [2-5].

Smoking is a main causative factor for initiation and progress of PD and diverse types of cancer [56], however acts as a confounder in studies that investigate the possible association between PD and several types of malignancies in which smoking is implicated in cancer development.

Few studies have been carried out in the literature regarding the oral or periodontal health status in patients who suffered from diverse types of cancer. Some oral manifestations may be detected in MM patients, such as swelling, pain, gingival bleeding, paresthesia and osteolytic lesions [14,16,18, 21,53], however, epidemiological data on the oral manifestations are scarce in the literature and restricted to case reports or case series [14-16,18,21]. Especially, the prevalence of caries and the periodontal status in MM patients have not been explored in full articles. Those issues should be addressed because chronic PD may progress in acute infections and potentially life-threatening systemic conditions in immuno-suppressed patients [39].

PPD is a critical index for assessing PD severity however in the present study PPD was not statistically significantly different between cases and controls. A similar prospective cross-sectional study, showed that individuals with oral or oropharyngeal cancer, had PPD 6.00 mm or greater of 76.0 % of the patients, whereas only 10.0 % in the control group showed the same PPD severity. A recent case-control study in lung cancer patients [37] showed that PPD was statistically significantly different between cases and controls whereas in another study in gastric cancer patients that finding was not recorded [38].

The results also revealed that MM patients showed significantly worse mean values in gingival inflammation severity, according to GI compared with controls, finding that was not confirmed by previous studies as similar reports have not been carried out, except for a recent study in which that finding was confirmed in gastric cancer patients [38]. On the other hand, GI use is limited in such epidemiological studies despite the fact that measures the inflammatory load of gingival tissue, whereas Hujoel et al. [33] suggested that gingival inflammation could be a risk factor for several types of cancer development.

Hemorrhagic episodes have been observed in 15-30% of MM patients [57]. In a recent review [58], gingival bleeding was reported in nearly 10% of the reported cases. The gingival bleeding assessed by the Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) currently suggests localized gingivitis [59,60]. Similar research showed that the mean GBI of the male patients (12.61 ± 9.27%) was much lower than the female’s mean GBI (22.35 ±20.5). The same study also recorded a statistical significance regarding gingival bleeding between elders and middle-aged females (p=0.05) among MM patients. Although gingival bleeding is strongly associated with inadequate dental plaque control, hormonal changes throughout life in middle-aged and older females may explain the higher GBI values [61]. GBI was defined as the percentage of sites with G-Index ≥2 [62].

Gingival inflammation (moderate/severe), as expressed by GI was statistically significant different between MM patients and healthy individuals in the current survey. However, that PD index has not been used for assessing possible differences between MM patients and healthy individuals.

No statistically significant difference was observed regarding BOP between the cases and the controls. This finding was not in accordance with the higher gingival inflammation scores recorded in the MM group. BOP is a critical indicator of a periodontal diagnosis, and the most reliable indicator of PD activity [63]. Similar findings have not been reported by other studies.

Also, statistically significant differences were not observed between the cases and the controls, regarding CAL values. Similar findings have not been reported by other investigators regarding the CAL index.

PlI assesses the accumulation of dental plaque on teeth surfaces. The current report showed no statistically significant differences regarding PlI between cases and controls. Only a study by Czerniuk et al. [64] confirmed that PlI in MM patients could lead to more severe infection of periodontal tissues according to PlI measurements, whereas Critchlow et al. [65] observed that head and neck cancer patients showed poor oral health and therefore more dental plaque accumulation at the time of diagnosis, whereas PD and dental caries were suggested as important clinical issues.

Similarly, few studies [66-68] have investigated the possible differences between cancer patients and healthy individuals concerning the number of missing teeth. The present report showed no statistically significant differences between the groups examined and tooth loss, whereas Bezerra et al. [61] investigated the oral status of elders and middle-aged MM patients observed that the elderly group showed to have significantly more missing teeth (p=0.05) than the middle-aged group. To be more specific the elders had a mean of 22.7 ± 6.25 missing teeth and the middle aged individuals, 14.4±9.5, whereas males had a mean of 16.0 ± 9.38 missing teeth, and females, 21.8 ±7.42.

The increased risk of periodontal tissue destruction in cancer patients has been proposed to be a result of psychological burden rather than disturbances in patients’ nutrition or alterations in the oral cavity regarding the saliva quantity/quality, or in the balance of micro-biological and immunological parameters in the oral cavity that could be affected because of the chemotherapy or radiotherapy [69,70]. It is also possible that MM patients could be more susceptible to the progression and destruction of periodontal tissue than the healthy population, suggestion that could be attributed to the fact that MM prognosis varies according to age and is worse in individuals over 65 years when compared to younger ones [7,9]. The aim of the present study was to investigate a comparison between MM patients and epidemiologically matched healthy individuals regarding several PD indices, and number of missing teeth and not to explore a possible association between PD indices, as etiological or risk factors, and MM development.

Some certain limitations should be taken into account during results interpreting. Case-control studies in contrast to prospective ones, do not have the reliability of the prospective ones, whereas selection, recall, random biases and the effect of known and un-known confounders are likely higher in retrospective studies and could lead to biased secondary associations regarding the indices examined. Another drawback is that the validity of the study could be affected by the fact that retrospective studies are based on questionnaires. Eventually, the decision to be enrolled in the current study older individuals who had at least 15 natural teeth would result in an underestimation as those individuals with previous PD may have had teeth extracted for periodontal reasons.

Conclusion

The present study showed that gingival inflammation, expressed by GI, was statistically significantly different between individuals who were suffered from MM and healthy individuals.

References

- Ramaiah KK., Joshi V., Thayi SR., Sathyanarayana P., Patil P., et al. Multiple myeloma presenting with a maxillary lesion as the first sign. Imag Sci Dent. 2015;45(1):55-60. [PubMed.]

- World Cancer Report World Health Organization. 2014. 2014;Chapter 2.3 and 2.6. ISBN 978-92-832-0429-9. [Ref.]

- PDQ Plasma Cell Neoplasms Including Multiple Myeloma;Treatment. 2021;National Cancer Institute. 1980. 2023. [Ref.]

- Ferri FF. Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2014 E-Book:5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2023;726 ISBN 978-0-323-08431-4. [Ref.]

- Georgakopoulou R., Fiste O., Sergentanis TN., Andrikopoulou A., Zagouri F., et al. Occupational Exposure and Multiple Myeloma Risk:An Updated Review of Meta- Analyses. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4179. [PubMed.]

- De Roos AJ., Spinelli J., Brown EB., Atanackovic D., Baris D., et al. Pooled study of occupational exposure to aromatic hydrocarbon solvents and risk of multiple myeloma. Occup Environmen Med. 2018;75(11):798-806. [PubMed.]

- Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma:2020 update on diagnosis., risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(5):548-567. [PubMed.]

- Myeloma. Myeloma., MGUS & related conditions. 2015. [Ref.]

- Palumbo A., Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Me. 2011;364(11):1046-1060. [PubMed.]

- Rajkumar SV., Dimopoulos MA., Palumbo A., Blade J., Merlini G., et al. International Myeloma Working Group. Update criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538-548. [PubMed.]

- Talamo G., Farooq U., Zangari M., Liao J., Dolloff NG., et al. Beyond the CRAB symptoms:a study of presenting clinical manifestations of multiple myeloma. Clin Lymph Myel Leuk. 2010;10(6):464-468. [PubMed.]

- Jain S., Kaur H., Kansal G., Gupta P. Multiple myeloma presenting as gingival hyper. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17(3):391-393. [PubMed.]

- Lee SH., Huang JJ., Pan WL., Chan CP. Gingival mass as the primary manifestation of multiple myeloma:report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82(1):75-79. [PubMed.]

- Zhao XJ., Sun J., Wang YD., Wuang L. Maxillary pain is the first indication of the presence of multiple myeloma:a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2(1):59-64. [PubMed.]

- Witt C., Borges AC., Klein K., Neumann HJ. Radiographic manifestations of multiple myeloma in the mandible:a retrospective study of 77 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55(5):450-453. [PubMed.]

- Epstein JB., Voss NJ., Stevenson-Moore P. Maxillofacial manifestations of multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57(3):267-271. [PubMed.]

- Mozaffari E., Mupparapu M., Otis L. Undiagnosed multiple myeloma causing extensive dental bleeding:report of a case and review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94(4):448-453. [PubMed.]

- Pinto LS., Campagnoli EB., Leon JE., Lopes MA., Jorge J. Maxillary lesion presenting as a first sign of multiple myeloma:case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12(5):344-347. [PubMed.]

- Segundo AV., Falcão MF., Correia-Lins Filho R., Soares MS., López J., et al. Multiple Myeloma with primary manifestation in the mandible:a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(4):232-234. [PubMed.]

- Shah A., Ali A., Latoo S., Ahmad I. Multiple Myeloma presenting as Gingival mass. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;9(2):209-212. [Ref.]

- Cardoso RC., Gerngross PJ., Hofstede TM., Weber DM., Chambers MS. The multiple oral presentations of multiple myeloma. Supp Care Cancer. 2014;22(1):259-267. [PubMed.]

- Troeltzsch M., Oduncu F., Mayr D., Ehrenfeld M., Pautke C., et al. Root resorption caused by jaw infiltration of multiple myeloma:report of a case and literature review. J Endod. 2014;40(8):1260-1264. [PubMed.]

- Roodman GD. Skeletal imaging and management of bone disease. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;313-319. [PubMed.]

- Adeyemo TA., Adeyemo WL., Adediran A., Akinbami AJ., Akanmu AS. Orofacial manifestation of hematological disorders:hemato-oncologic and immuno-deficiency dis- orders. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:688-697. [PubMed.]

- Stoopler ET., Vogl DT., Stadtmauer EA. Medical management update:multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:599-609. [PubMed.]

- Viggor SF., Frezzini C., Farthing PM., Freeman CO., Yeoman CM., et al. Amyloidosis:an unusual case of persistent oral ulceration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e46-50. [PubMed.]

- Khurram SA., McPhaden A., Hislop WS., Hunter KD. Crystal storing histiocytosis of the tongue as the initial presentation of multiple myeloma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:494-496. [PubMed.]

- Badros A., Weikel D., Salama A., Goloubeva O., Schneider A., et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients:clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):945-952. [PubMed.]

- Ise M., Takagi T. Bone lesion in multiple myeloma. Nippon Rinsho. 2007;65(12):2224-2228. [PubMed.]

- Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases:epidemiology. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1(1):1-36. [PubMed.]

- Holmstrup P., Poulsen AH., Andersen L., Skuldbøl T., Fiehn NE. Oral infections and systemic diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:575-598. [PubMed.]

- Michaud DS., Joshipura K., Giovannucci E., Fuchs CS. A prospective study of periodontal disease and pancreatic cancer in US male health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:171-175. [PubMed.]

- Hujoel PP., Drangsholt M., Spiekerman C., Weiss NS. An exploration of the periodontitis-cancer association. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:312-316. [PubMed.]

- Abnet CC., Qiao YL., Dawsey SM., Dong ZW., Taylor PR., et al. Tooth loss is associated with increased risk of total death and death from upper gastro-intestinal cancer., heart disease., and stroke in a Chinese population-based cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:467-474. [PubMed.]

- Rosenquist K., Wennerberg J., Schildt EB., Bladstrom A., Goran Hansson B., et al. Oral status., oral infections and some lifestyle factors as risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.A population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:1327-1336. [PubMed.]

- Michaud DS., Liu Y., Meyer M., Giovannucci E., Joshipura K. Periodontal disease., tooth loss., and cancer risk in male health professionals:a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:550-558. [PubMed.]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA. A Case-Control Study to Investigate an Association between Lung Cancer Patients and Periodontal Disease. Sci Arch Dent Sci. 2018;1:1 36-42. [PubMed.]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA., Oikonomou AA. A case-control study of the periodontal condition in gastric cancer patients. Stomatological Dis Sci. 2017;1:55-61. [Ref.]

- Hong CH., Napenas JJ., Hodgson BD., Stokman MA., Mathers-Stauffer V., et al. A systematic review of dental disease in patients undergoing cancer therapy. Supp Care Cancer. 2010;18:1007-1021. [PubMed.]

- Ludwig H., Novis Durie S., Meckl A., Hinke A., Durie B. Multiple Myeloma Incidence and Mortality Around the Globe;Interrelations Between Health Access and Quality., Economic Resources., and Patient Empowerment. Oncologist. 2020;25(9):e1406-e413. [PubMed.]

- Tonetti MS., Greenwell H., Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis:frame work and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:S149-S161. [PubMed.]

- Machuca G., Segura-Egea JJ., Jimenez-Beato G., Lacalle JR., Bullón P. Clinical indicators of periodontal disease in patients with coronary heart disease:A 10 years longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e569-574. [Ref.]

- International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies., multiple myeloma and related disorders:a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749LP-757. [PubMed.]

- Molloy J., Wolff LF., Lopez-Guzman A., Hodges JS. The association of periodontal disease parameters with systemic medical conditions and tobacco use. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:625-632. [PubMed.]

- Aurilio G., Piva F., Santoni M., Cimadamore A., Sorgentoni G., et al. The Role of Obesity in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients:Clinical-Pathological Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5683. [Ref.]

- Bagnardi V., Rota M., Botteri E., Tramacere I., Islami F., et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk:a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(3):580-593. [Ref.]

- Cutress TW., Ainamo J., Sardo-Infrri J. The community periodontal index of treatment needs CPITN;procedure for population groups and individuals. Int Dent J. 1987;37(4):222-233. [PubMed.]

- Wiebe CB., Putnins EE. The periodontal disease classification system of the American academy of periodontology an update. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:594-597. [PubMed.]

- Löe H. The Gingival Index., the Plaque Index., and the Retention Index Systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(6) Suppl:610-616. [PubMed.]

- Silness J., Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121-135. [PubMed.]

- Yoon HS., Wen W., Long J., Zheng W., Blot WJ., et al. Association of oral health with lung cancer risk in a low-income population of African Americans and European Americans in the Southeastern United States. Lung Cancer. 2019;127:90-95. [PubMed.]

- Kasamatsu A., Kimura Y., Tsujimura H., Kanazawa H., Koide N., et al. Maxillary swelling as the first evidence of multiple myeloma. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:439-536. [Ref.]

- Fregnani ER., Leite AA., Parahyba CJ., Nesrallah ACA., Ramos-Perez FMM., et al. Mandibular destructive radiolucent lesion:the first sign of multiple myeloma. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8 (4):e465-468. [PubMed.]

- Vucicevic-Boras V., Alajbeg I., Brozovic S., Mravak-Stipetic M. Burning mouth syndrome as the initial sign of multiple myeloma. Oral Oncol Extra. 2004;40(1):13-15. [Ref.]

- Reboiras LM., García GA., Antúnez LJ., Blanco CA., Gándara VP., et al. Anaesthesia of the right lower hemilip as a first manifestation of multiple myeloma. Presentation of a clinical case. Medicina Oral. 2001;6:168-172. [PubMed.]

- Sasco AJ., Secretan MB., Straif K. Tobacco smoking and cancer:a brief review of recent epidemiological evidence. Lung Cancer. 2004;45 Suppl 2:S3-9. [PubMed.]

- Kaushansky K., Williams WJ. Williams hematology. 9a ed. New York:McGraw-Hill Medical. 2015;2528. [Ref.]

- Xavier de Almeida TM., Feitosa Cavalcanti ÉF., da Silva A Freitas A., Pessoa de Magalhães RJ., Maiolino A., et al. Can dentists detect multiple myeloma through oral manifestations? Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2018;40(1):43-49. [PubMed.]

- Adam R., Goyal CR., Qaqish J., Grender J. Evaluation of an oscillating-rotating toothbrush with micro-vibrations versus a sonic toothbrush for the reduction of plaque and gingivitis:results from a randomized controlled trial. Int Dent J. 2020;70(Suppl. 1):S16-S21. [PubMed.]

- Trombelli L., Farina R., Silva CO., Tatakis DN. Plaque-induced gingivitis:case definition and diagnostic considerations. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:S44-S67. [PubMed.]

- Bezerra ML., CCM Alves L., Tabosa RAA., LO Dantas S., JF da Rocha T., et al. Oral Conditions of Elders and Middle-aged Individuals with Multiple Myeloma. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2021;22(6):610-614. [PubMed.]

- Carvajal P., Gómez M., Gomes S., Costa R., Toledo A., et al. Prevalence., severity., and risk indicators of gingival inflammation in a multi-center study on South American adults:a cross sectional study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2016;24(5):524-534. [Ref.]

- Lang NP., Joss A., Orsanic T., Gusberti FA., Siegrist BE. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease? J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:590-596. [PubMed.]

- Czerniuk MR., Jurczyszyn A., Charlinski G. State of Oral Mucosa as an Additional Symptom in the Course of Primary Amyloidosis and Multiple Myeloma Disease. Case Rep Med. 2014;ID 293063:1-5. [PubMed.]

- Critchlow SB., Morgan C., Leung T. The oral health status of pre-treatment head and neck cancer patients. Br Dent J. 2014;216:E1. [PubMed.]

- You Chen., Bao-ling Zhu., Cong-Cong Wu., Rui-fang Lin., Xi Zhang. Periodontal Disease and Tooth Loss Are Associated with Lung Cancer Risk. BioMed Research International. 2020;1-12. [Ref.]

- Hyung-Suk Yoon., Xiao-Ou Shu., Yu-Tang Gao., Gong Yang., Hui Cai., et al. Tooth Loss and Risk of Lung Cancer among Urban Chinese Adults:A Cohort Study with Meta-Analysis. Cancers Basel). 2022;14(10):2428. [PubMed.]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA. Association of Tooth Loss and Risk of Lung Cancer in a Greek Adult Population:A Case Control Study. J Dent Rep. 2020;1(1):1-16. [Ref.]

- Pearman T. Psychological factors in lung cancer:quality of life., economic impact., and survivorship implications. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26:69-80. [PubMed.]

- Konwinska MD., Mehr K., Owecka M., Kulczyk T. Oral Health Status in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy for Lung Cancer. Open J Dent Oral Med. 2014;2:17-21. [Ref.]