>Corresponding Author : Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos

>Article Type : Original Research Article

>Volume : 2 | Issue : 2

>Received Date : 2 Dec, 2022

>Accepted Date : 15 Dec, 2022

>Published Date : 21 Dec, 2022

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JDOE2200106

>Citation : Chrysanthakopoulos NA, and Vryzaki E. (2022) Investigation of the Association Between Psychological Parameters and Periodontal Disease in a Greek Adult Population: A Case - Control Study. J Dent Oral Epidemiol 2(2): doi https://doi.org/JDOE2200106

>Copyright : © 2022 Chrysanthakopoulos NA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Original Research Article | Open Access | Full Text

1Dental Surgeon, Oncologist, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece Resident in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, 401 General Military Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece

2Rio University Hospital of Patras, Greece

*Corresponding author: Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos, Dental Surgeon, Oncologist, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece Resident in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, 401 General Military Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece

Abstract

Objective: Epidemiologic studies provide strong evidence that chronic psychosocial stress and depression increase the risk of several systemic diseases and disorders. The current research aimed to investigate the association between stress, and depression with Periodontal Disease indices.

Material and Methods: The study counted with 280 individuals, males and females, 40–65 years of age, and were collected through a clinical examination and a modified standardized questionnaire. Case group included 140 individuals suffering from periodontal disease and control group consisted of 140 individuals with no history of periodontal disease. Psychological factors assessment included the following inventories, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Periodontal disease was assessed based on the following indices, Probing Pocket Depth (PPD), Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL), Gingival Index (GI) and Bleeding on Probing (BOP). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out to compare cases and controls.

Results: Mean probing depth and clinical attachment level were 4.60 ± 0.32 mm and 4.72 ± 1.12 mm in cases and 2.10 ± 0.50 mm and 1.86 ± 0.31 mm in controls, respectively (p < 0.05 and p< 0.01, respectively). Multivariate logistic regression model, controlling for confounding factors, demonstrated significant association between BAI and BDI with deeper periodontal pockets [p = 0.028 and p = 0.032, respectively], and moderate/severe CAL [p = 0.018 and p = 0.048, respectively]. The outcomes also revealed no significant associations between the mentioned psychological parameters with gingival inflammation (GI) and BOP. Those associations were confirmed after adjusting for possible confounders such as smoking, educational and socio-economic status.

Conclusion: Within the limits, the current research revealed significant associations between BAI and BDI and deeper periodontal pockets and moderate/severe CAL.

Keywords: Periodontal Disease; Psychosocial Factors; Life Events; Stress; Depression

Abbreviations: BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory, PPD: Probing Pocket Depth, CAL: Clinical Attachment Loss, GI: Gingival Index, BOP: Bleeding on Probing, PD: Periodontal Disease, rp: Reactive Protein, CI: Confidence Interval, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SD: Standard Deviations

Introduction

Previous investigations have focused on effects of psychosocial factors on the etiology of diverse systemic diseases, and several pathophysiologic mechanisms may explain the association of chronic stress and depression with systemic diseases [1-6]. Based on the fact that stress and/or depression affect a large proportion of the population worldwide and in addition, the effect of emotional and mental conditions on the individuals immune response, predispose the appearance of several pathological conditions [7,8]. Similar researches have focused on effects of psychosocial factors on the etiology and severity of periodontal disease (PD) [9-11].

PD is divided into two main types, gingivitis and periodontitis, is a chronic inflammatory disease caused by bacterial infection which invades gingiva and periodontal supporting tissues [12]. Periodontal bacteria [13] and viruses [14] are responsible for a host immuno-inflammatory response in periodontal tissues that leads to periodontal pocket formation, attachment and bone loss, and in case of aggressive and severe PD results in tooth loss. However, the presence of periodontal bacteria itself can not result in advanced tissue destruction in all individuals. This observation suggests an individual response and adaptation ability to a certain bacterial plaque quantity without disease progression [15].

Diverse behavioral factors such as oral hygiene, smoking, and stress, may change the health balance as act together leading to the PD development [16,17]. Similarly, diseases such as diabetes mellitus and epidemiological parameters such as poor nutrition, alcohol consumption and low socio-economic status also have been associated with a higher risk of periodontitis [18] and are able to modify the initiation and/or progression of periodontitis [19-21].

Psychological stress [22] and insufficient treatment [23] can influence the appearance and progression of several types of periodontitis [24]. Clinical evidence has provided an association between psychosocial stress and acute necrotizing PD, mainly necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis [25,26], and periodontitis [27-29]. Additionally, positive associations have been recorded between stress and depression and aggressive, rapidly progressive, periodontitis [30-32]. To be more specific depression has been associated with periodontitis in clinical studies in adults [9,23,33-38] and adolescents/young adults [39,40]. However, similar clinical researches failed to confirm such an association [41-44].

Experimental and clinical studies suggest the negative impact of chronic psychological stress and depression on the immune system and health. Brief stressors suppress cellular immunity and maintain the humoral immunity function. On the contrary, chronic stressors generally result in the immune system dysregulation, involving cellular and humoral pathways [45]. Moreover, in patients susceptible to periodontitis, stress can modify the host immune defense and facilitate the progression of periodontal infections [46].

Periodontitis patients often have higher systemic levels of C-reactive protein (C-rp), interleukin-6 (Il-6), interleukin-1 (Il-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [47]. Similarly, social stress increases the production of interleukin-1 beta (Il-1β) and TNF-α in CD11b+ spleen cells in response to P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide [48]. That finding suggests that stress can increase the responsiveness and production of inflammatory cytokines by macrophages in response to an oral pathogen. The mechanisms that stress is responsible for producing inflammation are complicated and bidirectional, as stress can produce inflammation and inflammation can produce stress. Those procedures involve pathways including genetic, neural, endocrine and immune interactions. Animal and human studies showed that stress influences the immune system in multiple ways as increases the secretion of neuroendocrine hormones, glucocorticoids and catecholamines. The activation of these hormones, leads to stress reactions that have harmful effects on immune functions, such as reduction of lymphocyte populations, lymphocyte proliferation, natural killer cell activity and antibody production and the re-activation of latent viral infections [49]. It has been accepted a general immunosuppressive action of stress, however it is now obvious that both immunosuppression and immune activation occur in diverse types of stress status [50].

It is possible that the mechanisms underlying the relationship of psychological stress and depression with periodontitis involve a combination of factors related to alterations in behavior and neuro-immunologic function. The neuro-immune-endocrine interaction by the action of hormones and biochemical mediators produced by the organism in anxiety or stress conditions, are able to alter extension and severity of periodontitis [10,17,51]. Glucocorticoids produced by the suprarenals can result in the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion, i.e., TNF-α, interleukins, and prostaglandins. On the contrary, catecholamines, epinephrine and nor-epinephrine, have the opposite actions, stimulating the generation and activity of proteolytic enzymes and prostaglandins, that can indirectly cause tissue and bone destruction [10, 52].

The modification of individuals’ health behavior is another possible mechanisms that stress and psychosocial factors influence periodontal health status, as individuals with high stress levels acquire harmful habits to periodontal health status, such as poor oral hygiene, abuse of smoking or alterations in nutrition habits with consequences to immunological system functions [10].

Investigations that have been based on serum and salivary stress-related steroids have revealed further evidence of an association between stress, depression, and PD. It has been recorded [53] that stress, depression and salivary cortisol scores were significantly associated with periodontitis severity and the number of missing teeth. The same article showed that the greatest CAL and highest number of missing teeth was recorded in individuals who reported neglecting their oral health during stressful or depressed periods. In addition, stress scores and salivary stress markers (chromogranin A, cortisol, alpha-amylase and beta-endorphin) were significantly associated with PD clinical indices [54], whereas similar associations have also been recorded between serum levels of cortisol and dehydroepi-androsterone-sulfate, the stress-related steroids, and PD indices [55,56].

Chronic or repeated stress, a typical symptom for mental illness individuals, induce a state of chronic inflammation through the activation of macrophages, dendritic cells, microglia, adipocytes and endothelium, which secrete cytokines and chemokines. Other effects concern altered cell circulation, natural killer cell cytotoxicity changes and alterations in the T-helper1/T-helper 2 balance, all of which could contribute to the potential for poor immune responsiveness to bacterias, susceptibility to infections, reactivation of latent viruses and delays in wound healing [57].

Clinical depressive disease is the affective disease that has constantly demonstrated immunologic alterations [58, 59]. This provided a possible explanation of depression as a significant risk indicator in PD.

It must be noticed that in many cases surveys exploring the association between depressive symptoms and periodontitis have been based on non-psychiatric study samples without consideration of comorbidities, limiting the validity of these surveys to identify an association between depression and PD.

In addition, stress and depression have a negative effect on treatment outcomes in periodontitis patients, findings that were in agreement with a previous article [60] indicating that psychosocial factors play a significant role in recovery from surgery and are predictive of surgical outcome. The aim of the current research was to investigate the association of stress, anxiety and depresssion with PD indices in Greek adult patients.

Materials and Methods

Study population design and data collection

The present research performed between June 2021 and April 2022 and consisted of 280 males and females who recruited from three private practices, two medical and one dental.

The study size was calculated according to the EPITOOLS guidelines (https://epitools.ausvet.com.au) determined with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and desired power 0.8. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations [61] for estimating periodontal incidence were used for assessing age group.

This study was not submitted by the Greek authorized committees (Ministry of Health, etc.) as was not an experimental one. All individuals signed an informed consent before taking part in the study.

Eligibility Criteria

In the study protocol enrolled 280 individuals, 145 males and 135 females. 140 individuals were selected in the case group and 140 in the control group. Cases were defined as individuals presenting at least 20 teeth and having periodontitis from stage I to IV [62] characterized as probing pocket depth (PPD) stage I [maximum PPD ≤ 4.0 mm] and stage II-IV [PPD ≤ 4.0 - ≥ 6.0 mm], clinical attachment loss (CAL) severity stage I [CAL: 1.0-2.0 mm], and stage II-IV [CAL: 3.00- ≥ 5.0 mm] [62].

Gingival index (GI) categorized corresponds to Löe [63] classification, and bleeding on probing (BOP) concerned absence and presence and considered positive if it occurred within15 seconds of probing [64].

To be eligible, cases and controls, should not have been treated by a conservative or a surgical process in their oral cavity in the last 6 months, or prescribed for systemic antibiotic or immune suppression medication or glucocorticoids or anti-depressive medication within the previous 6 months. Individuals with diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and other systemic diseases were not included in the study protocol.

Research Questionnaire

Cases and controls answered to a modified Minnesota Dental School Medical Questionnaire [65] that contained data concerning age, gender, smoking status, socio-economic and educational status, and data derived from their past Dental/Medical history.

Clinical measurements

All interproximal sites, mesial and distal, were measured using the following indices, PPD, CAL, GI and BOP in all quadrants apart from third molars and remaining roots. The worst values of the indices assesse to the nearest 1.0 mm and coded as dichotomous variables for each individual, using a Williams probe with a controlled force of 0.2 N (DB764R, Aesculap AG & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany). Clinical measurements were performed by one calibrated Dentist. For estimating the intra-examiner reproducibility, a randomly selected sample of 60 (20%) individuals re-examined clinically after a period of three weeks, without giving oral hygiene instructions to the individuals, by the same Dentist. No differences were recorded between the 1st and the 2nd clinical examination (Cohen's Kappa = 0.98).

Assessment of Periodontal Disease indices

PPD was dichotomously categorized as score 0: stage I and score 1: stage II-IV, and CAL severity was categorized as score 0: stage I, and score 1: stage II-IV [62]. GI categorized as score 0, which corresponds to Löe [63] classification 0 and 1, and-score 1, which corresponds to Löe classification as score 2 and 3. BOP was categorized as score 0: absence, and score 1: presence of BOP [64].

Psychosocial measurements

For assessing stress, anxiety and depression, individuals had to answer to two tests (BAI and BDI), assisted by a Psychology student trained and supervised by a professional of the field [66].

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), consisted of a self report scale with 21 items, concerning descriptive statements of anxiety symptoms rated by the subject on a four-point scale. The total score allows a classification of anxiety intensity levels:0-10 minimum;11-19 mild;20-30 moderate and 31-63 severe.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), also consisted of a self report scale with 21 items with four alternatives each, arranged in increasing degrees of depression severity. The intensity of depression corresponds to the following scores: 0-11 minimum depression;12-19 mild; 20-35 moderate and 36-63 severe [67,68].

Data analysis

PPD, CAL, GI, and BOP, were expressed by means and standard (SD) deviations, compared between groups were performed using paired t-test.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were applied to detect variables associated to the clinical outcome. The association between psychological parameters and PD indices was expressed by unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR’s) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The significance level was set in less than 5% (p < 0.05).

Results

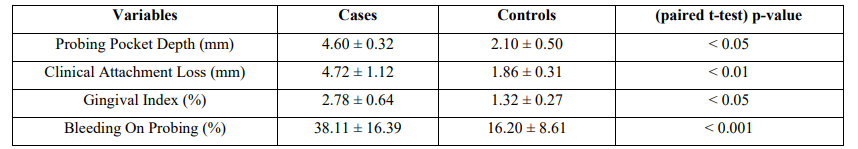

The mean age of cases and controls was 46.6 ± 2.7 and 48.3 ± 3.5 years, respectively. Table 1 shows the mean scores of PD clinical indices and respective standard deviations. There was a statistically significant difference between groups in all PD clinical parameters assessed (PPD<0 .05, CAL<0.01, GI<0.05, and BOP<0.001).

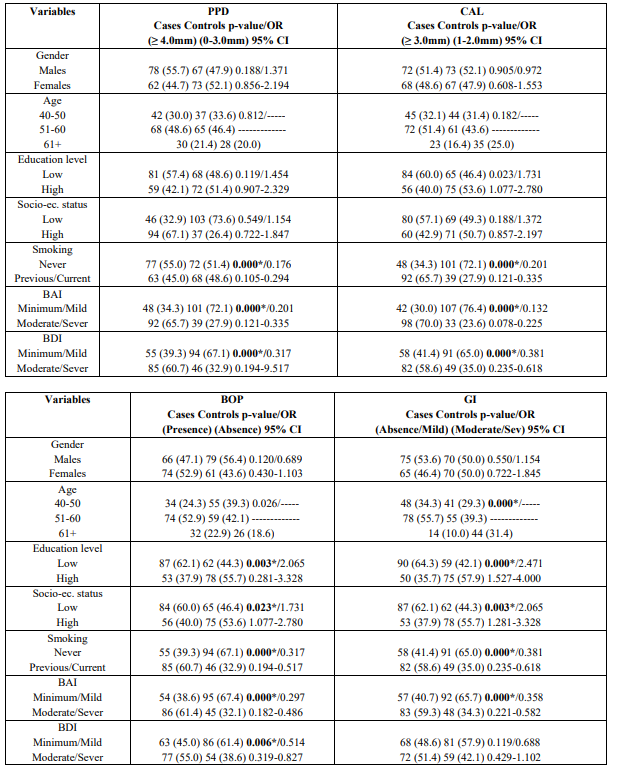

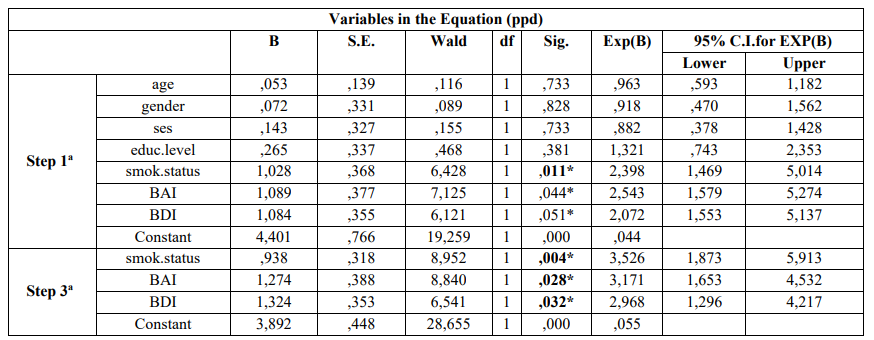

Table 2 presents the results after performing the univariate analysis model for each PD index. The model indicated that smoking [p = 0.000], BAI [p = 0.000] and BDI [p = 0.000] were statistically significantly associated with deeper periodontal pockets (≥ 4.0mm) and moderate/severe CAL (≥ 3.0 mm). It is shows that smoking [p = 0.000], BAI [p = 0.000], and BDI [p = 0.006] were statistically significantly associated with BOP presence, whereas advanced age [p = 0.000], lower educational level [p = 0.000], lower socio-economic status [p = 0.003], and BAI [p = 0.000] were statistically significantly associated with moderate/severe gingival inflammation as expressed by GI. Table 2 also indicates Unadjusted OR’s and 95% CI for each parameter examined. After performing the step 3a of the logistic regression analysis smoking [p = 0.004], BAI [p = 0.028], and BDI [p = 0.032] were found to be statistically significantly associated with deeper periodontal pockets. Adjusted OR’s and 95% CI for each variable examined is presented in the Table 3. It is also presents that after applied the step 2a the same parameters were statistically significantly associated with moderate/sever CAL [BAI and BDI, p = 0.018 and p = 0.048, respectively]. The same Table shows Adjusted OR’s and 95% CI.

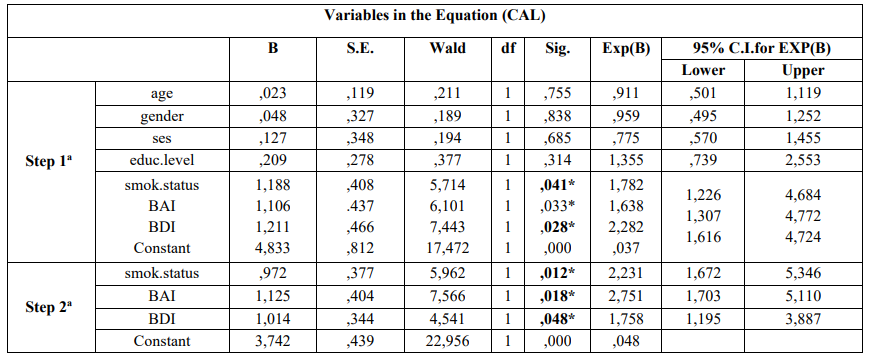

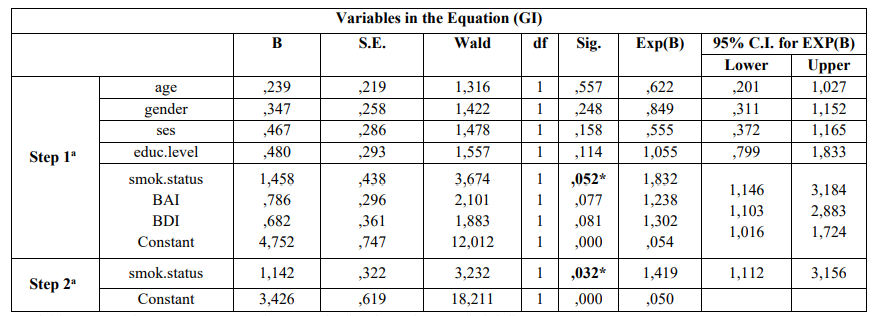

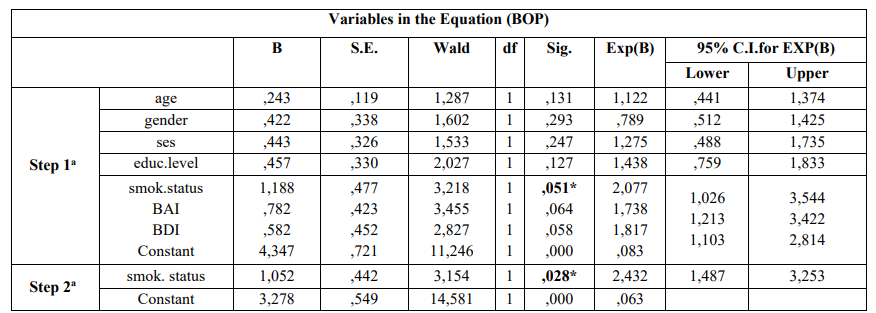

Table 4 indicates that after carried out the step 2a smoking status was statistically significantly associated with moderate/severe gingival inflammation (GI) [p = 0.032]. Adjusted OR’s and 95% CI are also presented. Smoking was the only epidemiological parameter that was statistically significantly associated with presence of BOP [p = 0.028] (Table 4).

Age, gender, educational and socio-economic status, were not statistically different between groups concerning PD indices examined (Tables 3,4). Logistic regression analysis was performed controlling for gender, age, educational and socio-economic level, and smoking status.

Table 1: PD Clinical Indices between Cases and Controls

Table 2: Univariate analysis of cases and controls regarding each independent variable

Table 3: Multivariate logistic regression analysis model of cases and controls regarding risk factors examined and PD according to Enter (first step) and Wald (last step)

a. Variable(s) entered on step 1: age, gender, ses, educ.level, smok.status, bai, bdi

Table 4: Multivariate logistic regression analysis model of cases and controls regarding risk factors examined and PD according to Enter (first step) and Wald (last step)

a.Variable(s) entered on step 1: age, gender, ses, educ.level, smok.status, bai, bdi

a. Variable(s) entered on step 1: age, gender, ses, educ.level, smok.status, bai, bdi

Discussion

The current research showed associations between anxiety and depression with smoking and some PD indices such as PPD and CAL, whereas no associations were recorded between common epidemiological parameters such as age, gender, educational and socio-economic status with risk of PD developing.

No association was recorded between increasing age and PD risk, finding that was not in agreement with other reports [69-73], but was in line with previous reports [74,75].

Similarly, no association was observed between male gender and PD development, finding that was not in agreement with those from previous reports [16,69,70,72,73,75] except for few studies [71,74]. These discrepancies could be attributed to the fact that males have poorer oral hygiene practices than females and less dental visit behaviors, whereas females usually are more aesthetically conscious, thus would be more worried about visiting the dentist [76].

PD indices, also, were not significantly higher between lower and higher educational level, finding that was in line with a previous research [72], whereas similar studies have revealed that low educational level was significantly associated with PD development and progression [72,73,75,77]. Worse PD indices have been found in individuals who lack education or having a basic primary education or had difficulties concerning their access to social health services [78].

Few previous studies have not recorded an association [73], or a weak association between SES and PD [16]. On the contrary statistically significantly associations between lower SES, which is a modifiable environmental factor, and PD development have been recorded in previous reports [75,77]. The current research recorded no association between those indices examined.

Smoking is a crucial risk factor for PD [79,80] according to previous epidemiological studies, and diverse mechanisms have been suggested in an attempt to explain its implication in PD pathogenesis and progression [70]. A significant association observed between smoking status and all PD indices in the current study, finding that has been confirmed by previous surveys [69-71,73]. This could be attributed to the crucial role of smoking as a modifiable environmental risk factor that affects host immune responses [79], however, to date it still remains unknown the mechanism which explains how smoking may affect PD. It is possible that genetic polymorphisms and genetic susceptibility may explain the mentioned influence [16].

Studies linking psychosocial factors to general health status have been carried out for many years [81,82]. However, most of those studies concerned a small number of individuals, and some have reported the association between psychosocial factors and oral health, in particular PD [27,29,83].

As mentioned psychological stress [22] and ineffective treatment [23] can lead to periodontitis appearance [24], and an association between psychosocial stress and acute necrotizing PD, mainly necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis [25,26] and periodontitis [27-29] has been found.

In a systematic review [32] was observed a positive association between stress/psychological factors and PD, and another one showed that mental illness, was significantly and independently associated with chronic periodontitis [84]. A clinico-biochemical study was found a positive association between stress, and PD indices such as PI, GI and PDI [55]. Another article showed an association between stress and PPD ≥ 4 mm, stress and CAL ≥ 5 mm, and stress and periodontitis [85]. Vettore, et al. [11] recorded that the frequency of moderate PPD (4-6 mm) and moderate CAL (4-6 mm) were significantly associated with higher trait anxiety scores after adjusting for socioeconomic data and cigarette smoking. Annsofi Johannsen, et al. observed that anxious individuals had a significantly higher GI than non-anxious ones, when controlling for smoking. Moreover anxious smokers with periodontitis had significantly more sites with pockets ≥ 5 mm, compare with non-anxious smokers [86]. Wellappulli and Ekanayake [87] recorded that the odds of having chronic periodontitis was nearly three times more in psychological distress individuals compared to those without psychological distress and stated that psychological distress was an independent risk factor for chronic periodontitis in the study population.

Similarly, Chiou et al., [88], found that psychological factors were significantly associated with CAL. Other authors who used different scales than BAI and BDI found associations between stress and periodontitis and between acute stressor(s) and periodontal status [11,46,89,90-92].

Depression has also been associated with periodontitis in clinical studies in adults [9,23,33-38] and adolescents/young adults [9,23,39,40,93-95].

Additionally, positive associations have been recorded between stress and depression and aggressive, rapidly progressive, periodontitis [30,31], whereas cross-sectional surveys have recorded associations between diverse psychological parameters and PD [23,28,36,83,96,97]. Li et al. [98] observed that the depression and anxiety indices of the periodontitis groups were higher than those of the control, and that the depression psychological factor was related to the progression of chronic periodontitis. In a similar article conducted by Ng and Leung [24] was revealed that depression, anxiety trait, and emotion-focused coping were also related to CAL.After performing logistic regression analysis was indicated that all these factors were significant risk indicators for periodontal attachment loss. Rosania, et al. [53] recorded that stress and depression, were associated with measures of PD, and that oral care neglect during periods of stress and depression was associated with attachment loss. Similar findings confirmed by Coelho et al. [99].

On the contrary, similar investigations demonstrated no significant association between psychosocial factors, stress and depression, and PD development in various populations samples [11,24,41-44,100]. In a systematic review [101], 15 articles were analyzed to assess the association between psychiatric status and PD. Five of those studies specifically examined depression and periodontitis, however, no significant association between psychiatric status and periodontitis were recorded. A considerable amount of heterogeneity between the included studies could explain those differences. Similarly, a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis also revealed no association between depression and periodontitis [102]. Solis, et al. [44] observed that patients with psychiatric symptoms, depression symptoms and with hopelessness were not at a greater risk of developing established periodontitis.

Those controversial findings may be explained because of the different approaches and designs applied in those studies. For instance matching is a challenge when investigating high prevalence disease as PD. Another reason is the effect of potential unknown confounders, and the fact that the periodontal condition of the participants was not usually reported in the studies. Another important issue was the definition of the tools of psychological analysis. To date there are no special indices available to define safely most psychiatric disorders [103]. In this study the scales BAI and BDI were preferred because of their validity, wide use in research, and facile and rapid appliance. They presented high internal consistency confirmed by Cronbach a values.

A great difficulty in the international literature concerns the establishment of certain definition criteria for PD [104,105]. That was the main reason why the current research tried to establish its own criteria for the definition of PD and health, constituting cases and controls with separate characteristics between them concerning PPD, CAL, GI and BOP.

Limitations to this study may concern reporting bias as individuals with the most severe depresssive symptoms may disproportionately choose not to be enrolled in the study protocol, or may be given unreliable answers, as it is well known that self-reported questionnaires could lead to the underestimation of the association examined. Another potential limitation concerns the retrospective feature of case-control studies compared to the prospective ones, whereas possible unknown confounders would result in biased associations.

Strengths of the current research concern the completeness of follow-up, the control of possible confounding and interaction by known risk factors, and the evaluation of PD status by oral clinical examination and not by a self-report questionnaire, as already mentioned.

Conflict of interest and source of funding statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- Guerry JD., Hastings PD. 2011; In search of HPA axis dysregulation in child and adolescent depression. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 14: 135-160. [PubMed.]

- Heim C., Newport DJ., Mletzko T., Miller AH., Nemeroff CB. 2008; The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 33: 693-710. [PubMed.]

- Joels M., Baram TZ. 2009; The neuro-symphony of stress. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10: 459-466. [PubMed.]

- Miller AH., Maletic V., Raison CL. 2009; Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 65: 732-741. [Ref.]

- Shelton RC., Claiborne J., Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M., Reddy R., Aschner M., et al. 2011; Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 16: 751-762. [PubMed.]

- Ulrich-Lai YM., Herman JP. 2009; Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10: 397-409. [PubMed.]

- Marucha PT., Kiecolt-Glaser JK., Farogehi M. 1998; Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosoma Med. 60: 362-365. [PubMed.]

- Ader R., Felten DL., Cohen N. 2001; Psychoneuroimmunology 3rd edition. New York: Academic. [Ref.]

- Moss ME., Beck JD., Kaplan BH., Offenbacher S., Weintraub JA., et al. 1996; Exploratory case-control analysis of psychosocial factors and adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 67: 1060-1069. [PubMed.]

- Genco RJ., Ho AW., Kopman J., Grossi SG., Dunford RG., et al. 1998; Tedesco LA. Models to evaluate the role of stress in periodontal disease. Ann Periodontol. 3: 288-302. [PubMed.]

- Vettore MV., da Silva AMM., Quintanilha RS., Lamarca GA. 2003; The relation-ship of stress and anxiety with chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 30: 394-402. [PubMed.]

- Highfeld J. 2009; Diagnosis and classification of periodontal disease. Austr Dent J. 54: S11-26. [PubMed.]

- Loesche WJ., Grossman NS. 2001; Periodontal disease as a specific., albeit chronic., infection: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev. 14(4): 727-752. [PubMed.]

- Grinde B., Olsen I. 2010; The role of viruses in oral disease. J Oral Microbiol. 12: 2. [PubMed.]

- Kinane DF., Stathopoulou PG., Papapanou PN. 2017; Periodontal diseases.Nat Rev Dis Prim. 3: 17038. [PubMed.]

- Genco RJ. 1996; Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 67: 1041-1049. [PubMed.]

- Rabin BS. 1999; Stress., Immune Function., and Health. New York: Wiley-Liss. 15(4): 260-260. [Ref.]

- Dyke TEV., Sheilesh D. 2005; Risk factors for periodontitis. J Int Acad Periodontol. 7: 3-7. [PubMed.]

- Lalla E., Papapanou PN. 2011; Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 7: 738-748. [PubMed.]

- Slots J. 2007; Herpesviral-bacterial synergy in the pathogenesis of human periodontitis.Curr Opin Infect Dis. 20: 278-283. [PubMed.]

- Slots J. 2000; Human viruses in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 53: 89-110. [PubMed.]

- Reners M., Brecx M. 2007; Stress and periodontal disease. Int J Dent Hyg. 5: 199-204. [PubMed.]

- Genco RJ., Ho AW., Grossi SG., Dunford RG., Tedesco LA. 1999; Relationship of stress., distress and inadequate coping behaviors to periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 70: 711-723. [PubMed.]

- Ng SK., Leung WK. 2006; A community study on the relationship between stress., coping., affective dispositions and periodontal attachment loss. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 34: 252-266. [PubMed.]

- Claypool DW., Adams FW., Pendell HW., Hartmann NA., Bone JF. 1975; Relationship between the level of copper in the blood plasma and liver of cattle. J Anim Sci. 41: 911-914. [PubMed.]

- Shannon IL., Kilgore WG., O’Leary TJ. 1969; Stress as a predisposing factor in necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. J Periodontol. 40: 240-242. [PubMed.]

- Freeman R., Goss S. 1993; Stress measures as predictors of periodontal disease-a preliminary communication. Com Dent Oral Epidemiol. 21: 176-177. [PubMed.]

- Green LW., Tryon WW., Marks B., Huryn J. 1986; Periodontal disease as a function of life events stress. J Hum Stress. 12: 32-36. [Ref.]

- Marcenes WS., Sheiham A. 1992; The relationship between work stress and oral health status. Soc Sci Med. 35: 1511-1520. [PubMed.]

- Davies RM., Smith RG., Porter SR. 1985; Destructive forms of periodontal disease in adolescents and young adults. Brit Dent J. 158: 429-436. [PubMed.]

- Page RC., Altman LC., Ebersole JL., Vandesteen GE., Dahlberg WH., et al. 1983; Rapidly progressive periodontitis. A distinct clinical condition. J Periodontol. 54: 197-209. [PubMed.]

- Peruzzo DC., Benatti BB., Ambrosano GM., Nogueira-Filho GR., Sallum EA., et al. 2007; Asystematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 78: 1491-1504. [PubMed.]

- Ababneh KT., Taha AH., Abbadi MS., Karasneh JA., Khader YS. 2010; The association of aggressive and chronic periodontitis with systemic manifestations and dental anomalies in a jordanian population: a case control study. Head Face Med. 6: 30. [Ref.]

- Johannsen A., Rydmark I., Soder B., Asberg M. 2007; Gingival inflammation., increased periodontal pocket depth and elevated interleukin-6 in gingival crevicular fluid of depressed women on long-term sick leave. J Periodontal Res. 42: 546-552. [PubMed.]

- Johannsen A., Rylander G., Soder B., Asberg M. 2006; Dental plaque., gingival inflammation., and elevated levels of interleukin-6 and cortisol in gingival crevicular fluid from women with stress-related depression and exhaustion. J Periodontol. 77: 1403-1409. [PubMed.]

- Silva AMM., Oakley DA., Newman HN., Nohl FS., Lloyd HM. 1996; Psychosocial factors and adult onset rapidly progressive periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 23: 789-794. [PubMed.]

- Ronderos M., Ryder MI. 2004; Risk assessment in clinical practice. Periodontol. 2000. 34: 120-135. [PubMed.]

- Saletu A., Pirker-Fruhauf H., Saletu F., Linzmayer L., Anderer P., et al. 2005; Controlled clinical and psychometric studies on the relation between periodontitis and depressive mood. J Clin Periodontol. 32(12): 1219-1225. [PubMed.]

- Dosumu OO., Dosumu EB., Arowojolu MO., Babalola SS. 2005; Rehabilitative management offered Nigerian localized and generalized aggressive periodontitis patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 6: 40-52. [Ref.]

- Lopez R., Ramirez V., Marro P., Baelum V. 2012; Psychosocial distress and periodontitis in adolescents. Oral Health Prev Dent. 10: 211-218. [PubMed.]

- Anttila SS., Knuuttila ML., Sakki TK. 2001; Relationship of depressive symptoms to edentu-lousness dental health., and dental health behavior. Acta Odontol Scand 59: 406-412. [PubMed.]

- Castro GD., Oppermann RV., Haas AN., Winter R., Alchieri JC. 2006; Association between psychosocial factors and periodontitis: a case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 33: 109-114. [PubMed.]

- Persson GR., Persson RE., MacEntee CI., Wyatt CC., Hollender LG., et al. 2003; Periodontitis and perceived risk for periodontitis in elders with evidence of depression. J Clin Periodontol. 30: 691-696. [PubMed.]

- Solis AC., Lotufo RF., Pannuti CM., Brunheiro EC., Marques AH., et al. 2004; Association of periodontal disease to anxiety and depression symptoms., and psychosocial stress factors. J Clin Periodontol. 31: 633-638. [PubMed.]

- Segerstrom SC., Miller GE. 2004; Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull J. 130: 601-630. [Ref.]

- Doyle CJ., Bartold PM. 2012; How does stress influence periodontitis? J Int Acad Periodontol. 14: 42-49. [PubMed.]

- Pussinen PJ., Paju S., Mantyla P., Sorsa T. 2007; Serum microbiala nd host-derived markers of periodontal diseases: a review. Curr Med Chem. 14: 2402-2412. [PubMed.]

- Bailey MT., Kinsey SG., Padgett DA., Sheridan JF., Leblebicioglu B. 2009; Social stress enhances IL-1beta and TNF-alpha production by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-stimulated CD11b+ cells. Physiol Behav J. 98: 351-358. [PubMed.]

- Marketon JIW., Glaser R. 2008; Stress hormones and immune function. Cellular Im-munol. 252: 16-26. [PubMed.]

- Nakata A. 2012; Psychosocialjob stress and immunity: a systematic review. Meth Mol Biol. 934: 39-75. [PubMed.]

- Dantzer R., O’Connor JC., Freund GG., Johnson RW., Kelley KW. 2008; From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 9: 46-56. [PubMed.]

- Breivik T., Thrane PS. 2001; Psychoneuroimmune interactions in periodontal disease. In: Ader R., Felten DL., Cohen N. eds). Psychoneuroimmunology. New York: Academic Cap. 63(3): 627-644. [Ref.]

- Rosania AE., Low KG., McCormick CM., Rosania DA. 2009; Stress., depression., cortisol., and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 80: 260-266. [PubMed.]

- Rai B., Kaur J., Anand SC., Jacobs R. 2011; Salivary stress markers., stress., and periodontitis: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 82: 287-292. [PubMed.]

- Goyal S., Jajoo S., Nagappa G., Rao G. 2011; Estimation of relationship between psychosocial stress and periodontal status using serum cortisol level: a clinico-biochemical study. Ind J Dent Res. 22: 6-9. [PubMed.]

- Ishisaka A., Ansai T., Soh I., Inenaga K., Awano S., et al. 2008; Association of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels in serum with periodontal status in older Japanese adults. J Clin Periodontol. 35: 853-861. [PubMed.]

- Glaser R., Kiecolt-Glaser JK. 2005; Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 5: 243-251. [PubMed.]

- Dorian BJ., Garfinkel PE., Keystone EC., Gorezynski R., Darby P., et al. 1985; Occupational stress and immunity. Psychosoma Med. 47: 77. [Ref.]

- Atanackovic D., Kroger H., Serke S., Deter HC. 2004; Immune parameters in patients with anxiety or depression during psychotherapy. J Affect Dis. 81: 201-209. [PubMed.]

- Rosenberger PH., Jokl P., Ickovics J. 2006; Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 14: 397-405. [PubMed.]

- World Health Organization. 1997; Oral health surveys: basic methods. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Ref.]

- Tonetti MS., Greenwell H., Kornman KS. 2018; Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Clin Periodontol. 45: S149-S161. [PubMed.]

- Löe H. 1967; The Gingival Index., the Plaque Index., and the Retention Index Systems. J Periodontol. 38: 610-616. [Ref.]

- Peikert SA., Mittelhamm F., Frisch E., Vach K., Ratka Krüger P., et al. 2020; Use of digital periodontal data to compare periodontal treatment outcomes in a practice-based research network PBRN): a proof of concept. BMC Oral Health. 20: 297. [Ref.]

- Molloy J., Wolff LF., Lopez-Guzman A., Hodges JS. 2004; The association of periodontal disease parameters with systemic medical conditions and tobacco use. J Clin Periodontol. 31: 625-632. [PubMed.]

- Beck AT., Epstein N., Brown G., Steer RA. 1998; An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 56: 893-897. [PubMed.]

- Beck AT., Steer RA., Garbing MG. 1988) Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-Five Years of Evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 8: 77-100. [Ref.]

- Beck AT., Steer RA. 1993; Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory., San Antonio: Psychological Corporation. [Ref.]

- Amran AG., Alhajj MN., Amran AN. 2016; Prevalence and Risk Factors for Clinical Attachment Loss in Adult Yemenis: A Community-Based Stud in the City of Dhamar. Am J Health Res. 4: 56-61. [Ref.]

- Rheu GB., Ji S., Ryu JJ., Lee JB., Shin C., et al. 2011; Risk assessment for clinical attachment loss of periodontal tissue in Korean adults. J Adv Prosthodontics. 3: 25-32. [Ref.]

- Rao SR., Thanikachalam S., Sathiyasekaran BWCS., Vamsi L., Balaji TM., et al. 2014; Prevalence and Risk Indicators for Attachment Loss in an Urban Population of South India: Oral Health Dent Manag. 13: 60-64. [PubMed.]

- Gamonal J., Mendoza C., Espinoza I., Muñoz A., Urzúa I. 2010; Clinical attachment loss in Chilean adult population: First Chilean National Dental Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 81(10): 1403-1410. [PubMed.]

- Haas AN., Wagner MC., Oppermann RV., Rösing CK., Albandar JM., et al. 2014; Risk factors for the progression of periodontal attachment loss: a 5-year population-based study in South Brazil. J Clin Periodontol. 41: 215-223. [PubMed.]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA. 2021; Evaluation of Risk Indicators for Clinical Attachment Loss in a Greek Adult Population. SVOA Dentistry 2(1): 39-47. [Ref.]

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA. 2018; Epidemiological risk factors for periodontal pockets and clinical attachment loss among Greek adults. Dent Oral Craniofac Res. 1: 114. [Ref.]

- Christensen LB., Petersen PE., Krustrup U., Kjøller M. 2003; Self-reported oral hygiene practices among adults in Denmark. Comm Dent Health. 20: 229-235. [PubMed.]

- Ababneh KT., Hwaij ZMFA., Khader YS. 2012; Prevalence and risk indicators of gingivitis and periodontitis in a Multi-Centre study in North Jordan: across sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 12: 1. [PubMed.]

- Ramírez Maya JC., Lopera NS., López AP., Agudelo-Suárez AA., Botero JE. 2017; Periodontal disease and its relationship with clinical and sociodemographic variables in adult patients treated in a service/ teaching institution. Rev Odontol Mex. 21: e160-e167. [Ref.]

- Palmer RM., Wilson RF., Hasan AS., Scott DA. 2005; Mechanisms of action of environmental factors-tobacco smoking. J Clin Periodontol. 32: 180-195. [PubMed.]

- Vouros ID., Kalpidis CDR., Chadjipantelis T., Konstantinidis AB. 2009; Cigarette smoking associated with advanced periodontal destruction in a Greek sample population of patients with periodontal disease. J Int Acad Periodontol. 11: 250-257. [PubMed.]

- DeLongis A., Coyne JC., Dakof G., Folkman S., Lazarus RS. 1982; Relationship of daily hassles., up-lifts., and major life events to health status. Health Psychol.1: 119-136. [Ref.]

- Cohen LH., Simons RF., Rose SC., McGowan J., Zelson MF. 1986; Relationships among negative life events., physiological reactivity., and health symptomatology. J Hum Stress. 12: 142-148. [PubMed.]

- Linden G., Mullally B., Freeman R. 1996; Stress and the progression of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 23: 675-680. [PubMed.]

- Teng HC., Lee CH., Hung HC., Tsai CC., Chang YY., et al. 2003; Lifestyle and psychosocial factors associated with chronic periodontitis in Taiwanese adults. J Periodontol. 74: 1169-1175. [PubMed.]

- Coelho JMF., Miranda SS., da Cruz SS., Trindade SC., Passos-Soares JDS., et al. 2020; Is there association between stress and periodontitis? Clin Oral Invest. 24: 2285-2294. [PubMed.]

- Johannsen A., Asberg M., Söder PO., Söder B. 2005; Anxiety., gingival inflammation and periodontal disease in non-smokers and smokers-an epidemiological study. J Clin Periodontol. 32: 488-491. [PubMed.]

- Wellappulli N., Ekanayake L. 2019; Association between psychological distress and chronic periodonitis in Sri Lankan adults. Comm Dent Health. 6: 293-297. [PubMed.]

- Chiou LJ., Yang YH., Hung HC., Tsai CC., Shieh TY., et al. 2010; The association of psychosocial factors and smoking with periodontal health in a community population. J Periodon Res. 45: 16-22. [PubMed.]

- Mannem S., Chava VK. 2012; The effect of stress on periodontitis: A clinic- biochemical study. J Ind Soc Periodontol. 16: 365-369. [PubMed.]

- Dolic M., Bailer J., Staehle HJ., Eickholz P. 2005; Psychosocial factors as risk indicators of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 32: 1134-1140. [PubMed.]

- Teng HC., Lee CH., Hung HC., Tsai CC., Chang YY., et al. 2003; Lifestyle and psychosocial factors associated with chronic periodontitis in Taiwanese adults. J Periodontol. 74: 1169-1175. [PubMed.]

- Hugoson A., Ljungquist B., Breivik T. 2002; The relationship of some negative events and psychological factors to periodontal disease in an adult Swedish population 50 to 80 years of age. J Clin Periodontol. 29: 247-253. [PubMed.]

- Hsu CC., Hsu YC., Chen HJ., Lin CC., Chang KH., et al. 2015; Association of periodon-titis and subsequent depression: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine. 94: e2347. [PubMed.]

- Aldosari M., Helmi M., Kennedy EN., Badamia R., Odani S., et al. 2020; Depression., periodontitis., caries and missing teeth in the USA., NHANES 2009-2014. Fam Med Comm Health. 8: e000583. [PubMed.]

- Friedlander AH., Mahler ME. 2001; Major depressive disorder. psychopathology., medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 132: 629-638. [PubMed.]

- Johannsen A., Asberg M., Söder PO., Söder B. 2005; Anxiety., gingival inflammation and pe-riodontal disease in non-smokers and smokers-an epidemiological study. J Clin Periodontol. 32: 488-491. [PubMed.]

- Klages U., Gordon A., Wehrbein H. 2005; Approximal plaque and gingival sulcus bleeding in routine dental care patients-relations to life stress., somatization and depression. J ClinPeriodontol. 32: 575-582. [PubMed.]

- Quan Li., Xu C., Wu Y., Guo W., Zhang L., et al. 2011; Relationship between the chronic periodontitis and the depression anxiety psychological factor. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 36: 88-92. [PubMed.]

- Coelho JMF., Miranda SS., da Cruz SS., Santos DND., Trindade SC., et al. 2020; Common mental disorder is associated with periodontitis. J Periodont Res. 55(2): 221-228. [PubMed.]

- Solis ACO. 2002; Associacāo da Doenc¸a Periodontal a Sintomas Ansiosos., Depressivos e Fatores Estressores Psicossociais. Thesis., Mestrado em Periodontia., Faculdade de Odontologia., Universidade de Sāo Paulo., Sāo Paulo. [PubMed.]

- Kisely S., Sawyer E., Siskind D., Lalloo R. 2016; The oral health of people with anxiety and depressive disorders-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Dis. 200: 119-132. [PubMed.]

- Cademartori MG., Gastal MT., Nascimento GG., Demarco FF., Corrêa MB. 2018; Is depression associated with oral health outcomes in adults and elders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest. 22: 2685-2702. [PubMed.]

- Menezes PR., Nascimento AF. 2000; Validade e confiabilidade das escalas de avaliacāo empsiquiatria. In: Gorenstein C., Andrade LHSG., and Zuardi AW eds). Escalas de Avaliacāo Clınica em Psiquiatria e Psicofarmacologia. 2: 23-28. [PubMed.]

- Genco RJ. 1996; Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 67: 1041-1049. [PubMed.]

- Baelum V. 1998; The epidemiology of destructive periodontal disease. Thesis., Department of Periodontology and Oral Gerontology., Faculty of Health Sciences., University of Aarthus., Aarthus. [Ref.]