>Corresponding Author : Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos

>Article Type : Original Research Article

>Volume : 2 | Issue : 1

>Received Date : 29 Aug, 2022

>Accepted Date : 09 Sep, 2022

>Published Date : 12 Sep, 2022

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JDOE2200105

>Citation : Chrysanthakopoulos NA and Oikonomou A. (2022) Oral Health Condition and Cardiovascular Disease in Greece: Results of a Questionnaire Research. J Dent Oral Epidemiol 2(1): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JDOE2200105

>Copyright : © 2022 Chrysanthakopoulos NA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Original Research Article | Open Access | Full Text

1Dental Surgeon, Oncologist, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece

2Resident in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, 401 General Military Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece and PhD in Oncology (cand)

3Internal Medicine, Private Practice, Patra, Greece

*Corresponding author: Nikolaos Andreas Chrysanthakopoulos, Dental Surgeon, Oncologist, Specialized in Clinical Oncology, Cytology and Histopathology, Dept. of Pathological Anatomy, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece and Resident in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, 401 General Military Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece and PhD in Oncology (cand)

Abstract

Objective: The aim of the current report was to examine the association between indices of oral health condition and cardiovascular disease in an adult Greek population.

Material and Methods:1,026 individuals derived from two medical and one dental practice consisted the study sample. The participants underwent an oral and dental clinical examination and answered a questionnaire regarding oral health, dental care habits, cardiovascular disease, socio-economic and educational status. Odd ratios for all cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and the subgroup stroke, myocardial infarction and hypertension were assessed with a logistic regression model adjusted for age, gender, smoking, educational and socio-economic status.

Results: After carrying out the logistic regression analysis model, an association between moderate/severe gingival inflammation (GI) and all CVD in general was observed (p=0.04, OR=1.87), and hypertension (p=0.03, OR= 1.73). There was also an association between severe PlI and all CVD (p=0.022, OR=1.78), and hypertension (p=0.015, OR=1.88). Moreover, an association was found between BOP all CVD (p=0.01, OR= 1.89), and hypertension (p=0.005, OR= 1.98).

Conclusion: The results indicated that oral health and, especially gingival inflammation (GI), plaque accumulation (PlI) and presence of bleeding on probing (BOP) were associated with CVD and hypertension.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Odds Ratio, Cardiovascular Disease, Risk Factor, Periodontal Disease

Abbreviations: CVD: Cardiovascular Diseases, GI: Gingival Inflammation, PlI: Plaque Index, BOP: Presence of Bleeding On Probing, PD: Periodontal Disease, DM: Diabetes Mellitus, CHD/CAD: Coronary Heart Disease And Artery Diseases, CRP: C Reactive Protein, ACVD: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases, HT: Hypertension, SAA: Serum Amyloid A, CI: Confidence Interval, MI: Myocardial Infarction, PPD: Probing Pocket Depth, CAL: Clinical Attachment Loss, OR: Odds Ratios, HF: Heart Failure, AF; Arterial Fibrillation, IE: Infective Endocarditis, PAD: Peripheral Artery Disease, PISA: Periodontal Inflamed Surface Area, LGI: Low Grade Inflammation

Introduction

Periodontal disease (PD), gingivitis and periodontitis affect many people worldwide. PD and especially periodontitis is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease. It is characterized by periodontal tissue inflammation and destruction of periodontal fibers and alveolar bone. Several bacteria and their antigens, endotoxins and inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and other biomarkers such as Interleukins are increased in chronic periodontitis and activate a systemic inflammatory reaction [1,2].

Previous reports have linked several risk factors to periodontitis such as advanced age, male gender, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), low socioeconomic status [3], dyslipidemias, and excessive alcohol consumption [4,5], whereas the genetic basis of chronic periodontitis has also been suggested [6].

In Greece studies regarding the prevalence/incidence of PD have not been carried out, however, a previous one observed that 27. 5% of Greek adults aged 35-44 years old had shallow and deep pockets, whereas 9. 5% of the individuals examined had healthy periodontal tissues. The same report also showed that the prevalence of severe PD was not high, and the periodontal health had improved since 1985, whereas a corresponding decrease in gingivitis prevalence was not detected [7].

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the western industrialized world [8]. The most common CVD risk factors are advanced age, male gender, hypertension, marked obesity, abnormal lipid metabolism, DM [9,10], cigarette smoking and physical inactivity, socioeconomic status, diet, fibrinogen levels, platelet P1 polymorphism [10-12], stress, excessive alcohol consumption, use of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, and possible endothelial cell injury [10,12,13]. The role of systemic chronic inflammation in CVD pathogenesis has also been proposed [11,14], whereas genetic influences in combination with environmental and behavioural risk factors have been suggested as its pathogenic factors [15]. However, a significant proportion of CVD is not explained by the traditional risk factors [12].

CVD is a group of vessels and heart disorders and include coronary heart disease and artery diseases (CHD/CAD) such as myocardial infarction (MI) and angina, cardiac arrhythmias (CA), stroke, hypertensive heart disease, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, aortic aneurysms, endocarditis, cerebrovascular disease, etc. [16].

Since the prevalence of PD and CVD are high, an association between them would affect many individuals. Several reasons for a possible association between PD and CVD have been proposed. Both diseases have various risk factors in common. Such factors are male gender, smoking, DM, dyslipidemias [5,17], and low socio-economic statuses and have been involved in CVD and periodontitis pathogenesis [18,19]. CVD pathogenesis also characterized by elevated serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen [20].

Especially, an association has also been recorded between PD and high levels of chronic inflammation serum markers [21] and based on the suggested relationship between chronic inflammation and CVD, it has been considered a role of PD in CVD etiology [11]. Periodontal bacteria or their products affect directly the vascular endothelial cells because of bacteremia or indirectly because of the inflammatory reaction, conditions that can lead to CVD pathogenesis [22].

Several researchers and clinicians have observed that periodontal infection contributes to periodontitis and leads to systemic effects as significant associations have been recorded between PD and systemic diseases or disorders such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ACVD), hypertension (HT), DM, respiratory diseases and allergies, endocrine disorders, cancer etc. [23]. Recent cohort and case-control researches have reported an association between both diseases [3,9,21,23-42], which is dependent on the severity of PD [3,43,44], whereas, few ones have shown no associations [45-50].

Previous studies have investigated the possible association between chronic periodontitis and HT, leading in controversial findings and focusing the need for more research [51-53].

Diverse possible explanations for the relationship between PD and CHD have been suggested. Periodontitis and CVD share several risk factors as already mentioned, another hypothesis suggested that there could be an underlying inflammatory response trait that places individuals at high risk for developing PD and atherosclerosis [44]. In addition, recent studies have shown that treatment of periodontitis reduces the serum concentration of inflammatory serum markers [20] and lipoproteins [31]. However, it remains controversial whether or not eliminating periodontal infections would contribute to the prevention of CVD [54].

A recent study reported similarities in the spectrum of bacteria in the oral cavity and in coronary plaques, and both diseases are characterized by an imbalanced immune reaction and a chronic inflammatory process [6], whereas significant similarities also exist in the pathogenetic processes of CVD and periodontitis, including monocyte hyper-responsiveness [55], elevations in systemic levels of C-RP [20], serum amyloid A (SAA) [56], and fibrinogen [57]. Moreover, genetic factors influence biological processes involved in both diseases, representing a potential mechanism that may link periodontitisto CVD [58] and could explain the positive association of these two pathological conditions [49], however these factors remain unknown at this time.

The inconsistency of the findings could be attributed to the different methods, criteria, and indices used to assess or define PD, as there is no uniform criteria to define PD or to measure the extent and severity of PD [59]. The exact mechanisms implicated in this association are not fully understandable, despite the large amount of studies present in the international literature. In addition, it is difficult to establish or not a cause-and effect association between CVD and PD because of the long follow-up period and because PD is involved in several phases of the formation, growth, and rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque [60], and consequently its action is not sensible [61].

PD and mainly periodontitis and CVD are widespread pathologic conditions, and therefore an association between both diseases is an important scientific subject from a preventive point of view. For these reasons there has been strong interest in evaluating whether PD is independently associated with CVD.

The aim of the current research was to investigate the possible association between oral health condition and CVD in a Greek adult population.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

The study sample consisted of 1, 026 individuals, 500 females and 526 males aged 45 to 85 years. The study sample size was calculated using the EPITOOLS guidelines (https://epitools. ausvet. com. au) determined with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and desired power 0. 8. In order to be obtained a representative study sample the study population was stratified by age and gender.

All the participants were patients of a private dental and two private medical practices. The participants underwent an oral and clinical examination and answered a health questionnaire. The research was carried out between December 2021 to June 2022.

Participants eligibility criteria

Participants’ selection criteria comprised age from 45 to 85 years old. The participants should have at least 20 natural teeth, since less than 20 teeth could lead to over-or underestimation of the parameters and the possible relationships examined [62].

All participants should not have treated by conservative or surgical periodontal therapy during the previous six months or prescribed systemic anti-inflammatory or antibiotics or other systemic medication during the previous six weeks. Participants suffered from acute infections, malignant diseases, or received systemic glucocorticoids treatment, were not enrolled in the research protocol [63]. The mentioned criteria were determined for reducing possible influences due to known or unknown confounders on the study indices examined and because of potential effects of those conditions on the oral status. Third molars and remaining roots were also not included in the research.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was a modified Minnesota Dental School Medical Questionnaire [64] included epidemiological parameters such as age, gender, smoking status (active smokers/non-smokers), educational and socio-economic status and data regarding the general medical history with reference to medication and several chronic systemic diseases and disorders such as DM, HT, Stroke, and Myocardial Infarction (MI).

For establishing the diagnosis of CVD the main question was whether a medical doctor had made the diagnosis of CVD. In addition, the CVD-patient should meet the following preconditions: ‘‘suffer from some degree of CVD, and sub-categories such as Stroke, MI and HT, do not suffer from any other relevant systemic pathological condition and usage as prescribed medication blockers for calcium channel (nifedipine or diltiazem), coumarin anti-coagulants and beta-blockers’’ [63].

The personal medical files of the participants were used for collecting additional data regarding the examined medical indices in the case that they did not recall details of their medical history.

Oral clinical examination

The oral and dental examinations were carried out by a well-trained and calibrated dentist and the following clinical indices were recorded: gingival index (GI), probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL)bleeding on probing (BOP)and Plaque Index (PlI). The mentioned indices were assessed by a William's 12 PCP probe (PCP 10-SE, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co. Inc., Chica-go, IL, USA) at six sites per tooth (disto-lingual, lingual, mesio-lingual, facial, mesio-facial, and disto-facial).

PPD severity was coded according to the criteria of the American Academy of Periodontology, as follows -score 0: moderate periodontal pockets, 4-6. 0 mm, and -score 1: advanced periodontal pockets, >6. 0 mm [65].

CAL severity was coded according to the criteria by Wiebe and Putnins [66], as follows: -score 0: mild, 1-2. 0 mm of attachment loss, and -score 1: moderate/severe, ≥ 3. 0 mm of attachment loss. Gingivitis severity was coded according to the following clinical signs: -score 0: no pathological signs of gingiva / mild gingival inflammation which corresponds to Löe and Silness [67] classification as score 0 and 1, and - score: moderate / severe gingival inflammation, which corresponds to Löe and Silness classification as score 2 and 3. PPD and CAL records were estimated according to the immediate full millimetre.

The presence or absence of BOP was coded according to the following clinical signs: -score 0: BOP absence, and -score 1: BOP presence and determined as positive in case the reaction was occurred within 15 seconds of probing.

Plaque Index (PlI), by Silness and Löe [68] was assessed by the same probe at the mentioned sites. The presence of dental plaque was determined whether it was visualized with naked eye or existed abundance of soft matter within the gingival pocket and/or on the tooth and gingival margin (score 2 and 3, respectively, according to PlI) and considered as present if at least one site showed the characteristic sign.

Tooth brushing was defined by the brushing frequency: ≥2 times per day versus less or rarely, whereas dental follow-up was defined as regular, ≥2 times per year and irregular, <2 times per year). Socio-economic status was classified: 0-1, 000 € per month for low-income level and 1, 001 € per month and above for high income level. Educational level was classified: university/ higher institutions for high educational level and primary-elementary/high-school for low educational level.

Ethical consideration

Experimental studies in Greece require a study protocol which must be examined and approved by authorized organizations such as Ministry of Health, Dental Schools, etc. The current research was not an experimental one and the participants signed an informed consent form.

Statistical analysis

For each individual the worst values of the examined periodontal indices GI, PPD, and CAL and the presence/absence of BOP and PlI were assessed at the six sites per tooth.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess which of the examined indices were best associated with CVD and its subgroups, MI, Stroke and HT.

Odds ratios (OR's) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for all types of CVD and the subgroups of myocardial infarction, stroke and hypertension were calculated with the mentioned model adjusted for age, gender, smoking, socio-economic and educational status.

Results

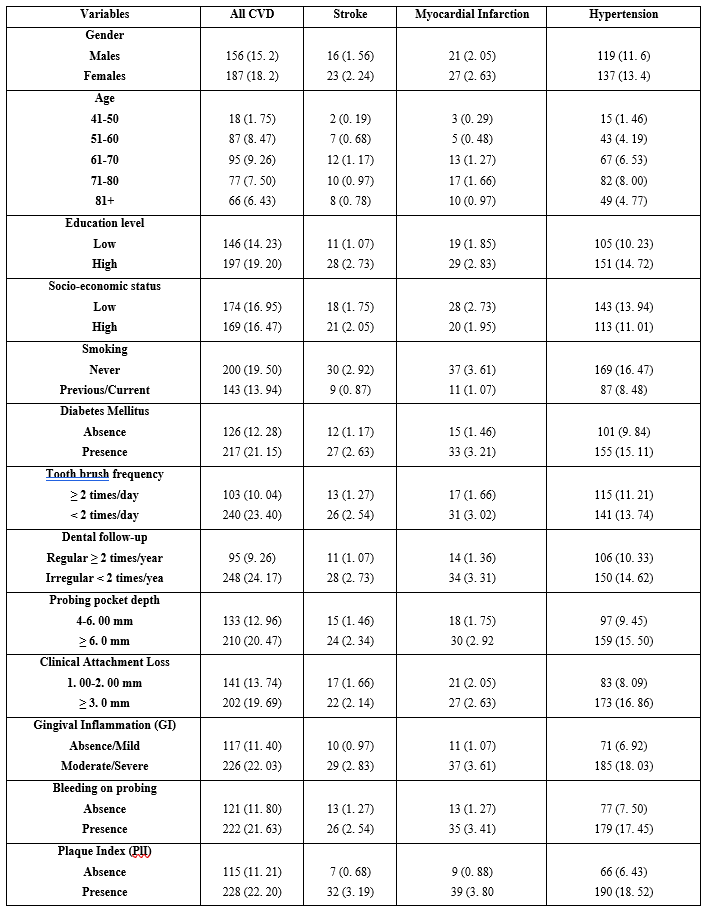

Out of 1, 026 individuals examined, 343 were suffered from CVD, and its sub-groups. Table 1 presents the frequencies of CVD variables in individuals and in the various subgroups, stroke, MI and HT.

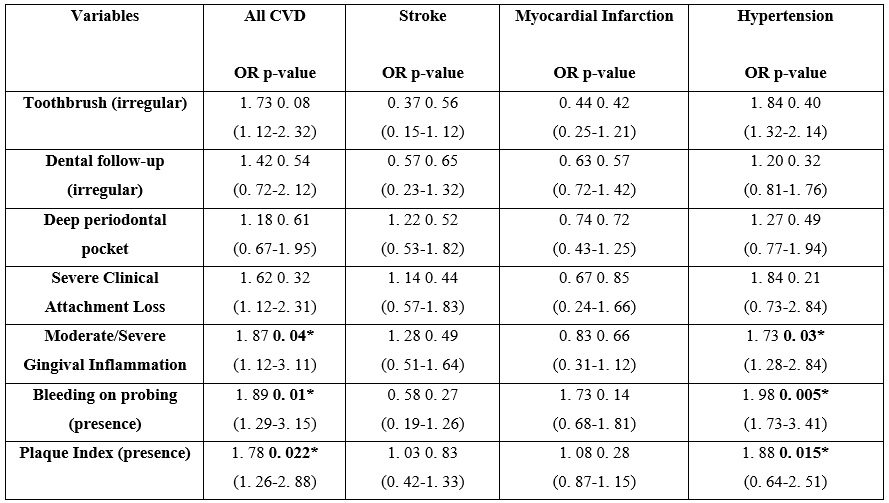

After carrying out the logistic regression analysis model, an association between moderate/ severe gingival inflammation (GI) and all CVD in general was observed (p=0. 04, OR=1. 87), and HT (p=0. 03, OR=1. 73). There was also an association between severe PlI and all CVD (p=0. 022, OR=1. 78), and HT (p=0. 015, OR=1. 88). Moreover, an association was found between BOP and all CVD (p=0. 01, OR=1. 89), and HT (p=0. 005, OR=1. 98).

No associations were detected between all CVD and irregular tooth brushing frequency and dental follow-up, deep periodontal pockets, and severe clinical attachment loss.

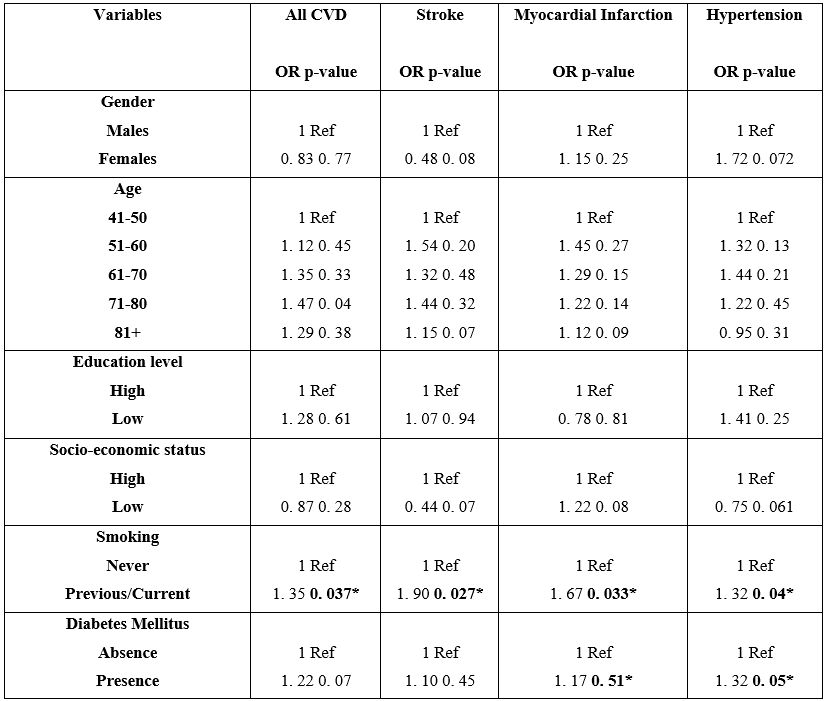

Associations were also found between smoking and all CVD (p=0. 037, OR=1. 35), smoking and Stroke (p=0. 027, OR=1. 90), smoking and MI (p=0. 033, OR=1. 67), and smoking and HT (p=0. 04, OR=1. 32). Moreover, there was an association between DM and high blood pressure (p=0. 05, OR=1. 32). No associations were detected between all CVD and gender, age, educational and socio-economic status.

Table 1: Frequencies of cardiovascular disease (CVD) variables in participants and in the various subgroups

Table 2: Odds ratios and 95% Confidence Interval for CVD associated with various indicators of oral health (each category refers to the no alternative in the questionnaire)

Table 3: Odds ratios for cardiovascular disease (CVD) associated with gender, age, educational and socio-economic status, smoking and DM (mark 1 in the ratio indicates the reference group)

(bold)*: p statistically significant

Discussion

The present study showed that gingival inflammation, as expressed by indices such as GI, BOP and PlI was associated with an increased risk of CVD, and especially HT. No association was recorded between PPD, CAL, regular tooth brushing frequency, regular dental follow-up and CVD and its subgroups.

MI, HT, atherosclerosis diseases for coronary artery, heart failure (HF), arterial fibrillation (AF), infective endocarditis (IE), and peripheral artery disease (PAD) have been associate with PD, and especially with periodontitis [69].

A large amount of studies [31,37,38,70-73] recorded that PD was a possible causal factor of CVD. Other investigations [29,40,41,74] suggested that there may be some association between periodontal inflammation and coronary heart disease (CHD). Several meta-analyses, case-control, cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies recorded that patients with chronic periodontitis were at greater risk for developing CHD, even after adjustment for a variety of potential confounders, whereas most of the results reporting a lack of association between both disease were from prospective studies [3,9,34,42,70-78].

Little [47] reported that none of the studies from 2005 to 2008 have shown a cause and-effect relationship between the examined diseases. Similar articles found no significant association between periodontitis and CHD [49,50,54,79-81]. This may be attributed to differences in the target population and the periodontitis definition, whereas in some studies, periodontitis was self-reported, and then no significant results were recorded [79,80]. Bokhari and Khan [46] reported that all studies on the relationship of PD to CVD were inconclusive and most of the data was based on epidemiological studies.

MI and PD have many common risk factors, such as smoking, DM, and infection [29,82]. Various studies indicated that PD was associated with an increased risk of MI [80,83-89], and the association appeared to be independent after adjusting for age, gender, smoking, educational and socio-economic status, DM, HT, and BMI. In addition, oral health in patients with MI has been found to be worse than healthy controls [90]. In these times, it is suggested that both MI and PD are multifactorial in nature, however, epidemiological studies failed to find an association between both diseases [79].

On the other hand, a recent systematic review by Sidhu detected that no association between MI and PD was confirmed [91].

A conducted meta-analysis indicated that periodontitis was associated with an increased risk of stroke [92], and in another survey in a Senegalese population was found that PD was associated with stroke [93].

Recent scientific evidence suggested a possible link between PD and systemic inflammation [21,56,57,94,95] which in turn is associated with an increased risk of HT [96,97]. HT is one of the main risk factors for CVD [98], and an important modifiable cardiovascular risk factor and consequently all measures aimed at identifying and controlling its development and progression are a worldwide public health priority [99].

Various researches have previously estimated the association between PD and HT, but so far little is known about the natural history of the mentioned association. Those studies reported a variety of PD measures and used different definitions of HT outcomes. PD was associated with a higher risk of HT [100-112], and especially in cases of severe periodontitis [52,53,100,101,105, 113,114], after adjusting for age, gender, current smoking and number of teeth. Another research suggested evidence of a causal relationship between periodontitis and HT using two complementary and independent research methods [115]. Self-reported assessed periodontitis was associated with incident arterial HT over an 8-year period [116].

It has also been suggested higher HT values in individuals with missing teeth [117,118], as periodontitis is the major cause of tooth extraction and tooth loss among adults. Moreover, treatment of periodontitis may reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 12 mmHg and 10 mmHg, respectively [119], whereas periodontitis can also result in ineffectiveness of antihypertensive medication [119,120].

Arterial HT and periodontitis often coexist, especially with parameters such as advanced age, male gender, cigarette smoking, DM, increased BMI, low socio-economic and educational status [121].

In a cross-sectional study among Puerto Rican elderly individuals, a significant and strong association between PD and blood pressure was observed but no association was found between clinically measured severe PD and self-reported hypertension diagnosis [51].

Cohort studies [106,122,123] confirmed a temporal association between periodontitis and incidence of HT although this was not statistically significant, whereas in a similar report a positive association was found, but after multivariate adjustments this association was no longer significant [81].

On the other hand, in a prospective study among U. S. health professional males, no association was found between severe periodontal bone loss and the risk of HT during 20 years of follow up [113]. In an analysis of 11, 029 U. S. individuals (17-year-old and older) [124] no significant association between PD severity and HT was recorded after adjusting for possible confounders.

One of the strengths of the mentioned articles was PD status clinical assessment. Another research showed no evidence that periodontitis is a risk factor for HT or that periodontal treatment has beneficial effects on blood pressure [125].

As already mentioned no association was found between the presence of PPD and CVD, finding that was in accordance with that from a previous article by Hakansson and Klinge [126], and Hujoel et al. [54]. This finding suggests no relationship between periodontitis and CVD. An explanation would agree with the findings of a previous article by Morrison et al. [127], who showed that the relative risk of dying of CHD was higher in individuals with mild or severe gingivitis than in those with periodontitis.

On the contrary, similar reports found significant results when PPD was used as a main indicator of periodontitis [33,37,39,101]. An interesting article in which smoking appeared to confound the association between periodontal condition and blood pressure [128], showed that the number of teeth with ≥4 mm periodontal pockets associated statistically significantly with systolic blood pressure in the whole study sample, whereas among never or daily smokers, no consistent nor statistically significant associations between the number of teeth with ≥4 mm periodontal pockets and systolic/diastolic blood pressure were observed. A similar survey by Tsakos et al. [52] confirmed the mentioned outcomes.

The current research showed no association between CAL and CVD development. However, Hung et al. [39] recorded that CAL could be an indicator for traditional risk factors for CHD. Andriankaja et al. [88] reported a slightly smaller effect of CAL on MI, obtaining OR 1. 34 for males and OR 2. 08 for females after adjustment for age, smoking, DM, physical activity, and BMI.

Machado et al. [129] also assessed the advancement of periodontitis on the basis of CAL and found that patients with periodontitis were characterized by an increased risk of HT, and that the age of the patient had a significant influence on this association after adjusting for age, BMI, and smoking. In another report was recorded that CAL and number of teeth missing were associated with blood pressure in post-menopausal females [130]. Similar results recorded by Tsakos et al. [52].

The outcomes also revealed that BOP was significantly associated with CVD, and especially HT. Johansson et al. [33] recorded that CHD patients had significantly higher BOP, whereas in a recent report by Pietropaoli et al. [131] the relationship between periodontal inflamed surface area (PISA) and BOP with the risk of arterial HT was assessed and a significant association demonstrated between BOP and the risk of arterial HT.

Pietropaoli et al. [132] in another survey showed that unstable periodontitis and gingivitis linked to gingival bleeding were associated with an increased risk of uncontrolled/high blood pressure. The measurement of BOP, that is a marker of active periodontal inflammation has been used for assessing the possible association between PD activity and HT. An analysis of a multi-ethnic US representative article indicated that BOP was the only measure consistently and significantly associated with raised systolic blood pressure after multivariate adjustments [52].

It is suggested that BOP contributes to increase the risk of high/uncontrolled BP, an effect that is amplified when BOP is considered in combination with chronic disease indices [132]. A case-control study demonstrated that BOP and bone loss, was independently associated with ischemic stroke [133].

Gingival inflammation as expressed by GI was found to be statistically significant with CVD development, HT especially, finding that was in accordance with that from a previous report [74]. A clinical survey by Darnaud et al. [134], for individuals ≥ 65 years, revealed no significant association between gingivitis and the risk of arterial HT. In contrast, among individuals < 65 years of age, an association was observed between gingivitis and the risk of arterial HT. A recent article [135], indicated that periodontitis was a CVD risk factor dependent on LGI (low-grade inflammation). Another survey by Hung et al. [39] showed that GI could be an indicator for CHD traditional risk factors, and the most plausible explanation was that periodontal indices were associated with poor oral hygiene, which in turn were associated with oral hygiene related cardiovascular risks as presence of worse periodontal indices, such as deep pockets and severe CAL.

Studies that have estimated the possible relationship between indices such as PlI have not been carried out. The current study showed a significant association between PlI and the risk of CVD development, especially HT. A statistically significant relationship between the systolic and diastolic blood pressure and oral hygiene index recorded in a research by Arowojolu et al. [136]. Darnaud et al. [134], in a clinical research showed an association between dental plaque and the risk of arterial HT among individuals <65 years but not among individuals ≥ 65 years, indicating a relationship between poor oral hygiene and risk of HT development.

Similarly, few articles have been examined oral hygiene indices such as regular toothbrush frequency and regular dental follow up with the risk of CVD development. Poor oral hygiene, never/rarely tooth brushing, was associated with higher levels of CVD risk [107]. Su-Yeon Hwang [137] recorded that tooth brushing frequency was significantly associated with incident HT after full adjustments for covariates, and similar articles suggested that poor oral health was a more important risk for CVD in younger and middle-aged individuals than in older ones [54].

Individuals with poor oral hygiene behavior are more likely to have a higher prevalence of HT, even before the appearance of periodontitis. Oral hygiene behavior may be considered an independent risk indicator for HT, and maintaining good oral hygiene may help to control and prevent HT.

The pathophysiologic mechanisms that may explain the association between periodontitis and HT concern endothelial dysfunction [57,138], oxidative stress [139,140], biologic and inflammatory pathways [57,138,140], bacteremia and immune response [141-143], interaction among DM insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and oxidative stress [144-146].

The most common CVD risk factors are advanced age, male gender, DM, cigarette smoking, socio-economic and educational status [9-12]. However, the current research showed that smoking was significantly associated with the risk of CVD development and its subgroups. The current research has certain limitations. As a retrospective study has a limited reliability compared with prospective ones. Another limitation was that it is not clear whether gingivitis or periodontitis precede CVD and because of that, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between diseases examined. As in the study protocol enrolled individuals who had at least 20 remaining natural teeth, it is possible an underestimation of older individuals who suffered from PD and who may have lost their teeth due to periodontal reasons. In addition, the present study recorded conventional periodontal indices and not more reliable PD parameters such as alveolar bone height / loss or the total number of remaining or missing teeth. Another minor limitation was that the diagnosis of CVD was based on self-reported data, consequently, responses of the out-patients to the questionnaire items may suffer from inaccuracy as they may under-report, over-report or choose not to report. This epidemiological issue could be solved by data collection from the personal medical files.

Conclusion

The current research indicated that oral health and, especially gingival inflammation, plaque accumulation and presence of bleeding on probing were associated with CVD and hypertension.

Conflict of interest and source of funding statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

- Socransky SS., Haffajee A. Microbial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of destructive periodontal diseases:a critical assessment. J Periodont Res. 1991;26:195–212. [PubMed.]

- Page RC. The pathobiology of periodontal diseases may affect systemic diseases:inversion of a paradigm. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:108–120. [PubMed.]

- Humphrey LL., Fu R., Buckley DI., Freeman M., Helfand M. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence:a systematic review and meta–analysis. J Gen Inter Med. 2008;23(12):2079–2086. [PubMed.]

- Karimbux NY., Saraiya VM., Elangovan S., Allareddy V., Kinnunen T., et al. Interleukin–1 gene polymorphisms and chronic periodontitis in adult whites:a systematic review and meta–analysis. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1407–1419. [PubMed.]

- Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10):1041–1049. [PubMed.]

- Schaefer AS., Richter GM., Groessner–Schreiber B., Noack B., Nothnagel M., et al. Identification of a shared genetic susceptibility locus for coronary heart disease and periodontitis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:2. [Ref.]

- Mamai–Homata E., Polychronopoulou A., Topitsoglou V., Oulis C., Athanassouli T. Periodontal diseases in Greek adults between 1985 and 2005–Risk indicators. Int Dent J. 2010;60:293–299. [Ref.]

- World Health Organization. The world health report:Bridging the gaps. Geneva:World Health Organization. 1995. [Ref.]

- Cabrera C., Hakeberg M., Ahlqwist M., Wedel H., Björkelund C., et al. Can the relation between tooth loss and chronic disease be explained by socioeconomic status? A 24–year follow–up from the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg., Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(3):229–236. [PubMed.]

- Scannapieco FA., Bush RB., Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis., cardiovascular disease., and stroke. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:38–53. [PubMed.]

- Ridker PM., Hennekens CH., Buring JE., Rifai N. C–reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–843. [PubMed.]

- Keil V. Coronary artery disease:the role of lipids., hypertension and smoking. Bas Res Cardiol. 2000;95(1):152–158. [PubMed.]

- Buja LM. Does atherosclerosis have an infectious etiology? Circul. 1996;94(5):872–873. [Ref.]

- Ridker PM., Cushman M., Stampfer MJ., Tracy RP., Hennekens CH. Inflammation., aspirin., and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. New Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):973–979. [PubMed.]

- Hegele RA. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 1996;246:21–38. [PubMed.]

- Sanz M., D’ Aiuto F., Deanfield J., Fernandez–Avilés F. European workshop in periodontal health and cardiovascular disease scientific evidence on the association between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases:a review of the literature. Eur Heart J. 2010;12:B3–12. [Ref.]

- Katz J., Flugelman MY., Goldberg A., Heft M. Association between periodontal pockets and elevated cholesterol and low density–lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J Periodontol. 2002;73:494–500. [PubMed.]

- Patel ST., Kent KC. Risk factors and their role in the diseases of the arterial wall. Semin Vasc Surg. 1998;11(3):156–168. [PubMed.]

- Salvi GE., Lawrence HP., Offenbacher S., Beck JD. Influence of risk factors on the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:173–201. [Ref.]

- Renvert S., Lindahl C., Roos–Jansaker AM., Lessem J. Short– term effects of an anti–inflammatory treatment on clinical parameters and serum levels of C– reactive protein and pro–inflammatory cytokines in subjects with periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:892–900. [PubMed.]

- Wu T., Trevisan M., Genco RJ., Falkner KL., Dorn JP., et al. Examination of the relation between periodontal health status and cardiovascular risk factors:serum total and high–density lipoprotein cholesterol., C–reactive protein., and plasma fibrinogen. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(3):273–282. [PubMed.]

- Asikainen SE. Periodontal bacteria and cardiovascular problems. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:495–498. [Ref.]

- Jepsen S., Kebschull M., Deschner J. Relationship between periodontitis and systemic diseases. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2011;54:1089–1096. [PubMed.]

- Blaizot A., Vergnes JN., Nuwwareh S., Amar J., Sixou M. Periodontal diseases and cardiovascular events:meta–analysis of observational studies. Int Den J. 2009;59(4):197–209. [PubMed.]

- Davé S., Dyke TV. The link between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease is probably inflammation. Oral Dis. 2008;14:95–101. [PubMed.]

- Oe Y., Soejima H., Nakayama H., Fukunaga T., Sugamura K., et al. Significant association between score of periodontal disease and coronary artery disease. Heart Vessel. 2009;24:103–107. [Ref.]

- Pinho MM., Faria–Almeida R., Azevedo E., Manso MC., Martins L. Periodontitis and atherosclerosis:an observational study. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:452–457. [PubMed.]

- Sfyroeras GS., Roussas N., Saleptsis VG., Argyriou C., Giannoukas AD. Association between periodontal disease and stroke. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1178–1184. [PubMed.]

- Shrihari TG. Potential correlation between periodontitis and coronary heart disease–an overview. Gen Dent. 2012;60:20–24. [PubMed.]

- Xu F., Lu B. Prospective association of periodontal disease with cardiovascular and all–cause mortality:NHANES III follow–up study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:536–542. [PubMed.]

- Pejcic A., Kesic L., Brkic Z., Pesic Z., Mirkovic D. Effect of periodontal treatment on lipoproteins levels in plasma in patients with periodontitis. South Med J. 2011;104(8):547–552. [PubMed.]

- Tang K., Lin M., Wu Y., Yan F. Alterations of serum lipid and inflammatory cytokine profiles in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic periodontitis:a pilot study. J Int Med Res. 2011;39(1):238–248. [PubMed.]

- Starkhammar–Johansson C., Richter A., Lundström A., Thorstensson H., Ravald N. Periodontal conditions in patients with coronary heart disease:a case–control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(3):199–205. [PubMed.]

- Joshipura K., Zevallos JC., Ritchie CS. Strength of evidence relating periodontal disease and atherosclerotic disease. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2009;30(7):430–439. [Ref.]

- Friedewald VE., Kornman KS., Beck JD., Genco R., Goldfine A., et al. The American journal of cardiology and journal of periodontology editors consensus:periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80(7):1021–1032. [PubMed.]

- Sanz ME., Lopez JC., Alonso JL. Six conformers of neutral aspartic acid identified in the gas phase. Phys Chem Chem Physics. 2010;12(14):3573–3578. [PubMed.]

- Latronico M., Segantini A., Cavallini F., Mascolo A., Garbarino F., et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease:an epidemiological and microbiological study. New Microbiol. 2007;30(3):221–228. [PubMed.]

- Bahekar AA., Singh S., Saha S., Molnar J., Arora R. The prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis:a meta–analysis. Amer Heart J. 2007;154(5):830–837. [PubMed.]

- Hung H–C., Colditz G., Joshipura KJ. The association between tooth loss and the self–reported intake of selected CVD–related nutrients and foods among US women. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(3):167–173. [PubMed.]

- Liu J., Wu Y., Ding Y., Meng S., Ge S., et al. Evaluation of serum levels of C– reactive protein and lipid profiles in patients with chronic periodontitis and/or coronary heart disease in an ethnic Han population. Quintes Int. 2010;41(3):239–247. [PubMed.]

- Matthews D. Possible link between periodontal disease and coronary heart disease. Evid Based Dent. 2008;9(1):8. [PubMed.]

- Ge S., Wu YF., Liu TJ., Meng S., Zhao L. Study of the correlation between moderately and severely chronic periodontitis and coronary heart disease. 2008;26(3):262–266. [Ref.]

- Geerts SO., Legrand V., Charpentier J., Alberts A., Rompen EH. Further evidence of the association between periodontal conditions and coronary artery disease. J Periodontol. 2004;75 9):1274–1280. [PubMed.]

- Beck KJ., Garcia R., Heiss G., Vokonas PS., Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10):1123–1137. [PubMed.]

- Beck JD., Eke P., Heiss G., Madianos P., Couper D., et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease:a reappraisal of the exposure. Circulation. 2005;112:19–24. [PubMed.]

- Bokhari SA., Khan AA. The relationship of periodontal disease to cardiovascular diseases–review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:177–181. [PubMed.]

- Little JW. Periodontal disease and heart disease:are they related? Gen Dent. 2008;56:733–737;quiz 738–739., 768. [PubMed.]

- Niedzielska I., Janic T., Cierpka S., Swietochowska E. The effect of chronic periodontitis on the development of atherosclerosis:review of the literature. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:103–106. [PubMed.]

- Tuominen R., Reunanen A., Paunio M., Paunio I., Aromaa A. Oral health indicators poorly predict coronary heart disease deaths. J Dent Res. 2003;82(9):713–718. [PubMed.]

- Stenman U., Wennstrom A., Ahlqwist M., Bengtsson.C, Björkelund C., et al. Association between periodontal disease and ischemic heart disease among Swedish women. A cross–sectional study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2009;67(4):193–199. [PubMed.]

- Rivas–Tumanyan S., Campos M., Zevallos JC., Joshipura KJ. Periodontal disease., hypertension., and blood pressure among older adults in Puerto Rico. J Periodontol. 2013;84:203–211. [PubMed.]

- Tsakos G., Sabbah W., Hingorani AD., Netuveli G., Donos N., et al. Is periodontal inflammation associated with raised blood pressure? Evidence from a National US survey. J Hypertens. 2010;28(12):2386–2393. [PubMed.]

- Tsioufis C., Kasiakogias A., Thomopoulos C., Stefanadis C. Periodontitis and blood pressure:The concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:1–9. [PubMed.]

- Hujoel PP., Drangsholt M., Spiekerman C., DeRouen TA. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease risk. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284(11):1406–1410. [PubMed.]

- Kang I–C., Kuramitsu HK. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein–1 by Porphyromonas gingivalis in human endothelial cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;34(4):311–317. [PubMed.]

- Glurich I., Grossi S., Albini B., Ho A., Shah R., et al. Systemic inflammation in cardiovascular and periodontal disease:comparative study. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(2):425–432. [Ref.]

- Loos BG., Craandijk J., Hoek FJ., Dillen W., Velden UV. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71(10):1528–1534. [PubMed.]

- Kullo IJ., Ding K. Mechanisms of disease:the genetic basis of coronary heart disease. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovascul Med. 2007;4(10):558–569. [PubMed.]

- Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases:epidemiology. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1(1):1–36. [PubMed.]

- Genco R., Offenbacher S., Beck J. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease:epidemiology and possible mechanisms. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:14S–22S. [PubMed.]

- Deliargyris EN., Marron I., Kadoma W., Marron I., Smith SC., et al. Periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;102(suppl 2):710. [Ref.]

- Machtei EE., Christersson LA., Grossi SG., Dunford R., Zambon JJ., et al. Clinical criteria for the definition of “established periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1992;63:206–214. [PubMed.]

- Machuca G., Segura–Egea JJ., Jiménez–Beato G., Lacalle JR., Bullón P. Clinical indicators of periodontal disease in patients with coronary heart disease:A 10 years longitudinal study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e569–574. [Ref.]

- Molloy J., Wolff LF., Lopez–Guzman A., Hodges JS. The association of periodontal disease parameters with systemic medical conditions and tobacco use. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:625–632. [PubMed.]

- American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on Chronic Periodontitis with Slight to Moderate Loss of Periodontal Support. J Periodontol. 2000;71:853–855. [PubMed.]

- Wiebe CB., Putnins EE. The periodontal disease classification system of the American Academy of Periodontology–an update. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:594–597. [PubMed.]

- Löe H., Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–551. [PubMed.]

- Silness J., Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. [PubMed.]

- Gao S., Tian J., Li Y., Liu T., Li R., et al. Periodontitis and number of teeth in the risk of coronary heart disease:an updated meta–analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e930112. 1044–1051. [Ref.]

- Helfand M., Buckley DI., Freeman M., Fu R., Rogers K., et al. Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease:A summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(7):496–507. [PubMed.]

- Gao K., Wu Z., Liu Y., Tao L., Luo Y., et al. Risk of coronary heart disease in patients with periodontitis among the middled–aged and elderly in China:a cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:621. [PubMed.]

- Desvarieux M., Demmer RT., Rundek T., Boden–Albala B., Jacobs DR., et al. Relationship between periodontal disease., tooth loss., and carotid artery plaque:the oral infections and vascular disease epidemiology study INVEST). Stroke. 2003;34(9):2120–2125. [PubMed.]

- Amar S., Gokce N., Morgan S., Loukideli M., Van Dyke TE., et al. Periodontal disease is associated with brachial artery endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation. Arterios Throm Vascul Biol. 2003;23(7):1245–1249. [PubMed.]

- Belinga LEE., Ngan WB., Lemougoum D., Essam Nlo’o ASP., Bongue B., et al. Association between periodontal diseases and cardiovascular diseases in Cameroon. J Publ Health Africa. 2018;9:761. [Ref.]

- Elter JR., Offenbacher S., Toole JF., Beck JD. Relationship of periodontal disease and edentulism to stroke/TIA. J Dent Res. 2003;82(12):998–1001. [PubMed.]

- Tiensripojamarn N., Lertpimonchai A., Tavedhikul K., Udomsak A., Vathesatogkit P., et al. Periodontitis is associated with cardiovascular diseases:a 13–year study. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(3):348–356. [PubMed.]

- Landi L., Grassi G., Sforza MN., Ferri C. Hypertension and periodontitis:an upcoming joint report by the Italian Society of Hypertension SIIA;and the Italian Society of Periodontology and Implantology SIdP). High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2021;28:1–3. [PubMed.]

- Beukers NGFM., Geert JMG., Heijden V., Wijk AJ., Bruno G., et al. Periodontitis is an independent risk indicator for atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases among 60., 174 participants in a large dental school in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:37–42. [PubMed.]

- Howell TH., Ridker PM., Ajani UA., Hennekens CH., Christen WG. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):445–450. [PubMed.]

- Noguchi S., Toyokawa S., Miyoshi Y., Suyama Y., Inoue K., et al. Five–year follow–up study of the association between periodontal disease and myocardial infarction among Japanese male workers:MY Health Up Study. J Public Health Oxf). 2015;37(4):605–611. [PubMed.]

- Goulart ACC., Armani F., Arap AM., Nejm T., Andrade JB., et al. Relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular risk factors among young and middle–aged Brazilians. Cross–sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2017;135(3):226–233. [PubMed.]

- Kjellstrom B., Gustafsson A., Nordendal E., Norhammar A., Nygren A., et al. Symptoms of depression and their relation to myocardial infarction and periodontitis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16(6):468–474. [PubMed.]

- Sanz M., Del CAM., Jepsen S., Gonzalez J., D'Aiuto F., et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases:Consensus report. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(3):268–288. [PubMed.]

- Wozakowska–Kaplon B., Wlosowicz M., GorczycaMichta I., Gorska R. Oral health status and the occurrence and clinical course of myocardial infarction in hospital phase:A case–control study. Cardiol J. 2013;20(4):370–377. [Ref.]

- Kodovazenitis G., Pitsavos C., Papadimitriou L., Vrotsos IA., Stefanadis C., et al. Association between periodontitis and acute myocardial infarction:A case–control study of a non–diabetic population. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49(2):246–252. [PubMed.]

- Ryden L., Buhlin K., Ekstrand E., de FU., Gustafsson A., et al. Periodontitis increases the risk of a first myocardial infarction:A report from the PAROKRANK Study. Circulation. 2016;133(6):576–583. [PubMed.]

- Górski B., Nargiełło E., Grabowska E., Opolski G., Górska R. The Association Between Dental Status and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction Among Poles:Case–control Study. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2016;25(5):861–870. [PubMed.]

- Andriankaja OM., Genco RJ., Dorn J., Dmochowski J., Hovey K., et al. Periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction:The role of gender and smoking. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:699–705. [PubMed.]

- Cueto A., Mesa F., Bravo M., Ocaňa–Riola R. Periodontitis as risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. A case control study of Spanish adults. J Periodont Res. 2005;40:36–42. [PubMed.]

- Mattila KJ., Nieminen MS., Valtonen VV., Rasi VP., Kesaniemi YA., et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298(6676):779–781. [Ref.]

- Sidhu RK. Association between acute myocardial infarction and periodontitis:A review of the literature. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2016;18(1):23–33. [PubMed.]

- Lafon A., Pereira B., Dufour T., Rigouby V., Giroud M., et al. Periodontal disease and stroke:A meta–analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(9):1155–1157. [PubMed.]

- Diouf M., Basse A., Ndiaye M., Cisse D., Lo CM., et al. Stroke and periodontal disease in Senegal:case–control study. Publ Health. 2015;129(12):1669–1673. [PubMed.]

- Joshipura KJ., Wand HC., Merchant AT., Rimm EB. Periodontal disease and biomarkers related to cardiovascular disease. J Dent Res. 2004;83:151–155. [PubMed.]

- Slade GD., Offenbacher S., Beck JD., Heiss G., Pankow JS. Acute–phase inflammatory response to periodontal disease in the US population. J Dent Res. 2000;79:49–57. [PubMed.]

- Boos CJ., Lip GY. Is hypertension an inflammatory process? Cur r Pharm Des. 2006;12:1623–1635. [PubMed.]

- Li JJ. Inflammation in hypertension:primary evidence. Chin Med J Engl). 2006;119:1215–1221. [PubMed.]

- Kannel WB. Elevated systolic blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:251–255. [PubMed.]

- Lanau N., Mareque–Bueno J., Zabalza M. Does Periodontal Treatment Help in Arterial Hypertension Control? A Systematic Review of Literature. Eur J Dent. 2021;15(1):168–173. [PubMed.]

- Aguilera E., Suvan J., Buti J., Czesnikiewicz–Guzik M., Ribeiro AB., et al. Periodontitis is associated with hypertension:a systematic review and meta–analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:28–39. [PubMed.]

- Holmlund A., Holm G., Lind L. Severity of periodontal disease and number of remaining teeth are related to the prevalence of myocardial infarction and hypertension in a study based on 4., 254 subjects. J Periodontol. 2006;77(7):1173–1178. [PubMed.]

- Angeli F., Verdecchia P., Pellegrino C., Pellegrino RG., Pellegrino G., et al. Association between periodontal disease and left ventricle mass in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:488–492. [PubMed.]

- Inoue K., Kobayashi Y., Hanamura H., Toyokawa S. Association of periodontitis with increased white blood cell count and blood pressure. Blood Press. 2005;14:53–58. [PubMed.]

- Desvarieux M., Demmer RT., Jacobs Jr DR., Rundek T., Boden–Albala B., et al. Periodontal bacteria and hypertension:the oral infections and vascular disease epidemiology study INVEST). J Hypertens. 2010;28:1413–1421. [PubMed.]

- Martin–Cabezas R., Seelam N., Petit C., Agossa K., Gaertner S., et al. Association between periodontitis and arterial hypertension:a systematic review and meta–analysis. Am Heart J. 2016;180:98–112. [PubMed.]

- Kawabata Y., Ekuni D., Miyai H., Kataoka K., Yamane M., et al. Relationship between prehypertension/hypertension and periodontal disease:a prospective cohort study. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29:388–396. [PubMed.]

- De Oliveira C., Watt R., Hamer M. Toothbrushing., inflammation., and risk of cardiovascular disease:results from Scottish Health Survey. BMJ. 2010;340:c2451. [PubMed.]

- Zhao MJ., Qiao YX., Wu L., Huang Q., Li BH., et al. Periodontal Disease Is Associated With Increased Risk of Hypertension:A Cross–Sectional Study. Front Physiol. 2019;10:440. [PubMed.]

- Lee JH., Lee JS., Park JY., Choi JK., Kim DW., et al. Association of lifestyle–related comorbidities with periodontitis:a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Medicine. 2015;94:e1567. [PubMed.]

- Zainoddin NBMM., Taib H., Awang RAR., Hassan A., Alam MK. Systemic conditions in patients with periodontal disease. Int Med J. 2013;20:363–366. [Ref.]

- Zhao MJ., Qiao YX., Wu L., Huang Q., Li BH., et al. Periodontal Disease Is Associated With Increased Risk of Hypertension:A Cross–Sectional Study. Front Physiol. 2019;10:440. [PubMed.] [PubMed.]

- Sofi–Mahmudi A. Is periodontitis associated with hypertension? Evid Based Dent. 2020;21(4):132–133. [PubMed.]

- Rivas–Tumanyan S., Spiegelman D., Curhan GC., Forman JP., Joshipura KJ. Periodontal Disease and Incidence of Hypertension in the Health Professionals Follow–Up Study. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(7):770–776. [PubMed.]

- Zeigler CC., Wondimu B., Marcus C., Modeer T. Pathological periodontal pockets are associated with raised diastolic blood pressure in obese adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:41. [Ref.]

- Czesnikiewicz–Guzik M., Osmenda G., Siedlinski M., Nosalski R., Pelka P., et al. Causal association between periodontitis and hypertension:evidence from Mendelian randomization and a randomized controlled trial of non–surgical periodontal therapy. Europ Heart J. 2019;40:3459–3470. [PubMed.]

- Carra MC., Fessi S., Detzen L., Darnaud., Chantal J., et al. Self–reported periodontal health and incident hypertension:longitudinal evidence from the NutriNet–Santé e–cohort. J Hypertens. 2021;39(12):2422–2430. [PubMed.]

- Völzke H., Schwahn C., Dörr M., Schwarz S., Robinson D., et al. Gender differences in the relation between number of teeth and systolic blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1257–1263. [PubMed.]

- Taguchi A., Sanada M., Suei Y., Ohtsuka M., Lee K., et al. Tooth loss is associated with an increased risk of hypertension in postmenopausal women. Hypertension. 2004;43:1297–1300. [PubMed.]

- Surma S., Romanczyk M., Witalinska–Labuzek J., Czerniuk MR., Labuzek K., et al. Periodontitis., blood pressure., and the risk and control of arterial hypertension:epidemiological., clinical., and pathophysiological aspects–review of the literature and clinical trials. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2021;23(5):27. [PubMed.]

- Aguilera EM., Suvan J., Orlandi M., Catalina QM., Nart J., et al. Association between periodontitis and blood pressure highlighted in systemically healthy individuals:results from a nested case–control study. Hypertension. 2021;77(5):1765–1774. [Ref.]

- Pinto RD., Pietropaoli D., Munoz–Aguilera E., D'Aiuto F., Czesnikiewicz–Guzik M., et al. Periodontitis and hypertension:is the association causal? High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2020;27:281–289. [RPubMedef.]

- Morita T., Yamazaki Y., Fujiharu C., Ishii T., Seto M., et al. Association between the duration of periodontitis and increased cardiometabolic risk factors:a 9–year cohort study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2016;14:475–482. [PubMed.]

- Lee JH., Oh JY., Youk TM., Jeong SN., Kim YT., et al. Association between periodontal disease and non–communicable diseases:a 12–year longitudinal health examined cohort study in South Korea. Medicine. 2017;96:e7398. [PubMed.]

- D'Aiuto F., Sabbah W., Netuveli G., Donos N., Hingorani AD., et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with severe periodontitis in a large U.S. population–based survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3989–3994. [PubMed.]

- Brignardello–Petersen R. There is still no high–quality evidence that periodontitis is a risk factor for hypertension or that periodontal treatment has beneficial effects on blood pressure. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(4):e31. [PubMed.]

- Hakansson J., Klinge B. Oral health and cardiovascular disease in Sweden. Results of a national questionnaire survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:254–259. [PubMed.]

- Morrison HI., Ellison LF., Taylor GW. Periodontal disease and risk of fatal coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1999;6:7–11. [PubMed.]

- Ollikainen E., Saxlin T., Tervonen T., Suominen AL., Knuuttila M., et al. Association between periodontal condition and blood pressure is confounded by smoking. Acta Odontol Scand. 2022;80(6):457–464. [PubMed.]

- Machado V., Aguilera E., Bothelo J., Hussain SB., Leira Y., et al. Association between periodontitis and high blood pressure:results from the study of Periodontal Health in Almada–Seixal SoPHiAS). J Clin Med. 2020;9:1585. [Ref.]

- Gordon JH., LaMonte MJ., Genco RJ., Zhao J., Cimato TR., et al. Association of Clinical Measures of Periodontal Disease with Blood Pressure and Hypertension among Postmenopausal Women. J Periodontol. 2018;89(10):1193–1202. [PubMed.]

- Pietropaoli D., Del Pinto R., Ferri C., Marzo G., Giannoni M., et al. Association between periodontal inflammation and hypertension using periodontal inflamed surface area and bleeding on probing. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:160–172. [PubMed.]

- Pietropaoli D., Monaco A., D’Aiuto F., Aguilera Muñoz E., Ortu E., et al. Active gingival inflammation is linked to hypertension. J Hypertens. 2020;38(10):2018–2027. [PubMed.]

- Lafon A., Tala S., Ahossi V., Perrin D., Giroud M., et al. Association between periodontal disease and non–fatal ischemic stroke:a case–control study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):687–693. [PubMed.]

- Darnaud C., Thomas F., Pannier B., Danchin N., Bouchard P. Oral health and blood pressure:the IPC cohort. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1257–1261. [PubMed.]

- Hansen PR., Holmstrup P. Cardiovascular Diseases and Periodontitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1373:261–280. [PubMed.]

- Arowojolu MO., Oladapo O., Opeodu OI., Nwhator SO. An Evaluation of the possible relationship between Chronic Periodontitis and Hypertension. J West African Coll Surg. 2016;6(2):20–38. [PubMed.]

- Hwang S., Oh H., Rhee M., Kang S., Kim H. Association of periodontitis., missing teeth., and oral hygiene behaviors with the incidence of hypertension in middle–aged and older adults in Korea:A 10–year follow–up study. J Periodontol. 2022;21. [PubMed.]

- Nardin ED. The role of inflammatory and immunological mediators in periodonti is and cardiovascular disease. Ann Periodont. 2001;6:30–40. [PubMed.]

- D’Aiuto F., Nibali L., Parkar M., Patel K., Suvan J., et al. Oxidative stress., systemic inflammation., and severe periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1241–1246. [PubMed.]

- Brock GR., Butterworth CJ., Matthews JB., Chapple IL. Local and systemic total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis and health. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:515–521. [PubMed.]

- Sandros J., Papapanou PN., Nannmark U., Dahlén G. Porphyromonas gingivalis invades human pocket epithelium in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 1994;29:62–69. [PubMed.]

- Cairo F., Gaeta C., Dorigo W., Oggioni MR., Pratesi C., et al. Periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. A controlled clinical and laboratory trial. J Periodontal Res. 2004;39:442–446. [PubMed.]

- Kozarov EV., Dorn BR., Shelburne CE., Dunn Jr WA., Ann P. Human atherosclerotic plaque contains viable invasive Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:17–18. [PubMed.]

- Grossi SG., Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus:a two–way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–61. [PubMed.]

- Benguigui C., Bongard V., Ruidavets JB., Chamontin B., Sixou M., et al Metabolic syndrome., insulin resistance., and periodontitis:a cross–sectional study in a middle–aged French population. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:601–608. [PubMed.]

- Marchetti E., Monaco A., Procaccini L., Mummolo S., Gatto R., et al. Periodontal disease:the influence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metabol. 2012;9:88–100. [Ref.]