>Corresponding Author : Douha El Karoini

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 5 | Issue : 12

>Received Date : 12 Dec, 2025

>Accepted Date : 20 Dec, 2025

>Published Date : 24 Dec, 2025

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500161

>Citation : El Karoini D, Maghfour H, Sakim M, Benssouda M, Aicha G, et al. (2025) Ovarian Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Discovered During Pregnancy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Case Rep Med Hist 5(12): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500161

>Copyright : © 2025 El Karoini D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access | Full Text

1Resident Physician, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the Ibn Rochd University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

2Professor in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the Ibn Rochd University of Hospital in Casablanca Morocco

*Corresponding author: El Karoini Douha, Resident Physician, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Ibn Rochd University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

Abstract

Ovarian cancer ranks fifth among cancers associated with pregnancy. In pregnant women, the situation is even more complex because symptoms are often vague or masked by the physiological changes of pregnancy, and diagnostic evaluation (imaging, tumor markers) and therapeutic management (surgery, chemotherapy) require constant adaptation in order to preserve both maternal and fetal health.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Ovarian Cancer, Carcinomatosis

Abbreviations: AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein

Introduction

Cancer associated with pregnancy is a rare but increasingly reported condition, linked to the postponement of pregnancy to a later age and the parallel increase in the incidence of neoplasms in the fourth decade of life [1,2]. In terms of frequency, it ranks fifth among cancers associated with pregnancy, after breast, thyroid, cervical, and Hodgkin's lymphoma [3]. It complicates approximately 1 in 1,000 pregnancies [3–5] and thus represents a real diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

In pregnant women, the situation is all the more complex because the symptoms are often vague or masked by the physiological changes of pregnancy, and because diagnostic evaluation (imaging, tumor markers) and therapeutic management (surgery, chemotherapy) require constant adaptation in order to preserve both maternal and fetal health [6,7].

In this context, we report the case of a 30-year-old patient in whom obstetric ultrasound revealed, at 20 weeks of amenorrhea, an ovarian mass suggestive of neoplasia complicated by peritoneal carcinomatosis. This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties of this rare entity and will serve as a starting point for a review of the literature.

Medical Observation

This is a 30-year-old patient with no particular medical or surgical history, being monitored for a single-fetus pregnancy. During an obstetric ultrasound performed at 20 weeks of amenorrhea, two bilateral adnexal masses measuring 6x6 cm were noted, suspected of being malignant.

Magnetic resonance imaging was requested, which confirmed two suspicious formations measuring approximately 6 cm each. There was also a moderate amount of peritoneal effusion with no visible adenopathy. The uterus was the site of a progressing singleton pregnancy.

Surgical exploration was performed, revealing a moderate amount of peritoneal effusion, disseminated carcinomatous nodules, a resected omental mass, and an ovarian mass adhering to the omentum and small intestine, which was also resected. The pathological examination concluded that it was a high-grade papillary serous adenocarcinoma, infiltrating the right ovary, measuring 14 cm in length, with invasion of the peritoneum and omentum. The provisional pathological stage was determined to be pT3.

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary gynecological oncology consultation meeting. Initial chemotherapy was chosen, combining weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin. Treatment was initiated, with a planned halt at around 35 weeks of gestation to allow for delivery. During treatment, the ACE marker showed a gradual decrease. After three cycles, a follow-up MRI scan performed in the third trimester showed a partial response, characterized by a regression of the restrictive component of the ovarian masses and peritoneal effusion. The patient then received a fourth course of treatment before the end of her pregnancy.

Obstetric follow-up revealed a break in the fetal growth curve, with an estimated weight below the first percentile. The patient received corticosteroid therapy with a scheduled cesarean section. This resulted in the birth of a female newborn weighing 1900 g, with Apgar scores of 10/10. During the same operation, the patient underwent totalization surgery for cancer, including a total hysterectomy with contralateral adnexectomy, an infracolic omentectomy, and resection of residual peritoneal adhesions and nodules. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was then referred back to oncology for adjuvant chemotherapy in the postpartum period.

Discussion

The diagnosis of ovarian cancer during pregnancy remains a real challenge, as symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, constipation, dyspnea, or increased abdominal girth can be confused with those of pregnancy, leading to diagnostic delay [8,9]. Conversely, acute abdominal complications such as torsion, tumor rupture, or intraperitoneal hemorrhage are relatively common and may reveal an ovarian mass [10].

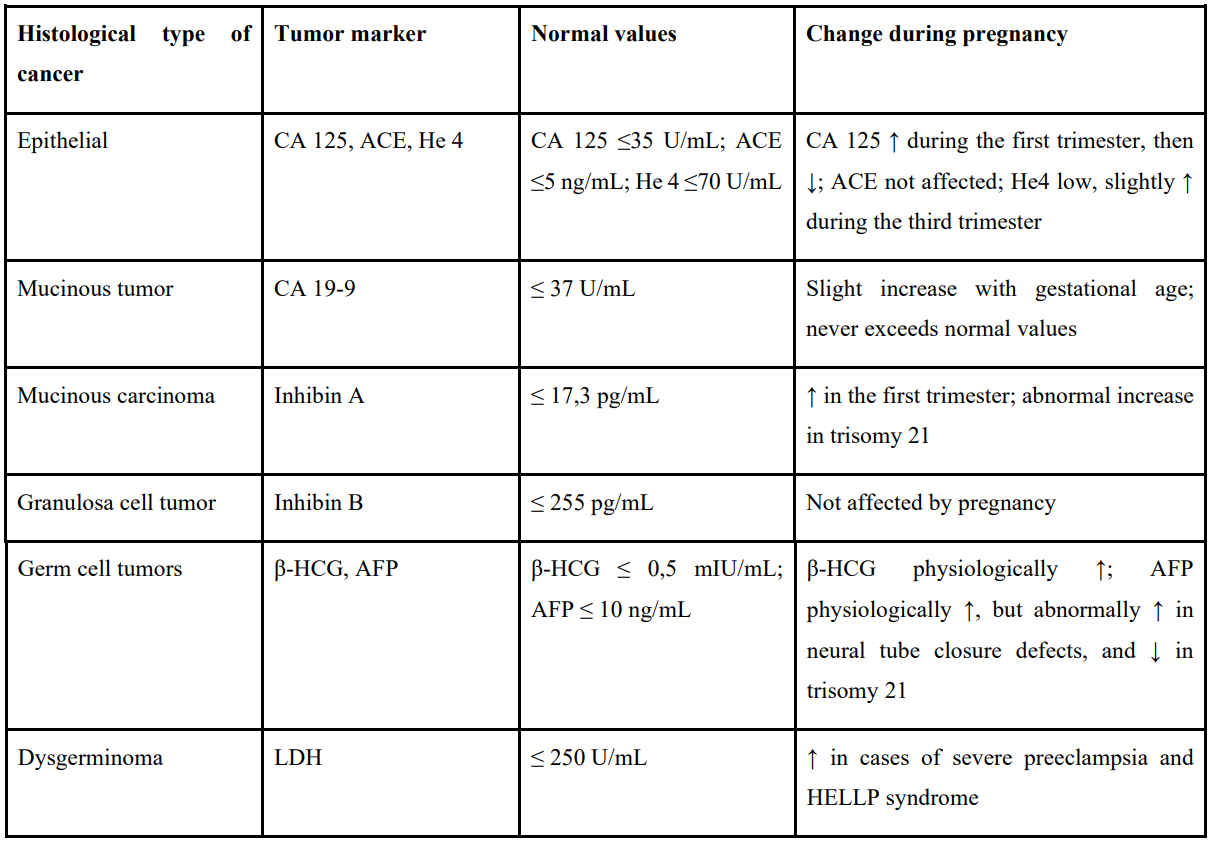

Tumor markers should be interpreted with caution, as some are physiologically elevated during pregnancy. Table 1 summarizes the main markers according to histological type and their variations during pregnancy. CA125 and hCG are often elevated, particularly in the first trimester, while others such as inhibin B, LDH, HE4, CA19-9, CEA, and AMH should remain within normal ranges and can therefore aid in diagnosis [11,12,13]. Unexplained levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and inhibin A may falsely suggest a fetal abnormality such as neural tube closure defects or trisomy 21 but may sometimes indicate the presence of an adnexal tumor [14].

Routine obstetric ultrasound helps diagnose asymptomatic ovarian masses [8]. As a second-line test, MRI is the most appropriate examination for pregnant women, allowing for better characterization of complex masses and assessment of peritoneal or lymph node spread [15,16]. CT scans, on the other hand, are not recommended due to the risks associated with ionizing radiation for the fetus [17,18]. The use of gadolinium remains controversial because this product can cross the placenta [19]. Ultrasound signs suggestive of malignancy include tumor size greater than 10 cm, rapid growth, solid areas, thick septa, papillary projections, bilaterality, or the presence of ascites [20,21].

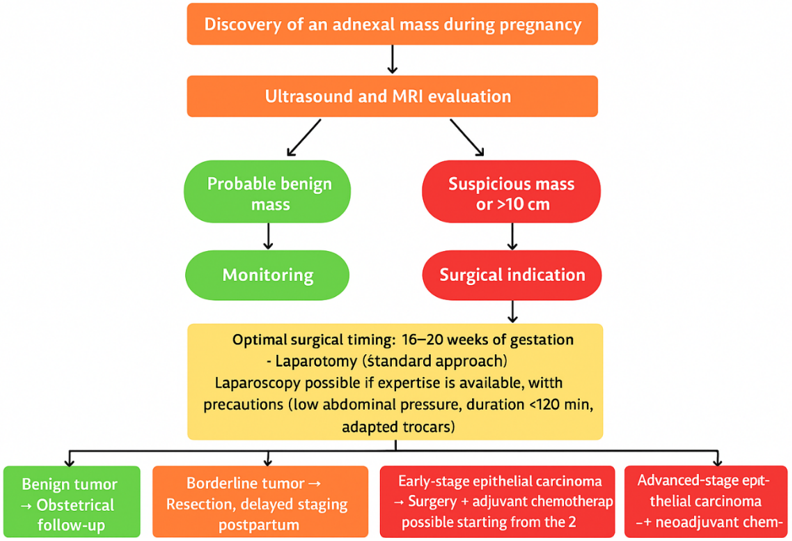

There are no formal consensus recommendations for the management of ovarian cancer during pregnancy. Early publications recommended immediate laparotomy regardless of gestational age [22], but the current strategy is individualized according to gestational age, maternal-fetal status, and the desire to continue the pregnancy [23]. Non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy remains rare, but when indicated, its timing is crucial: too early, it exposes the patient to a risk of miscarriage (before 14 weeks of gestation, progestogen supplementation is recommended); too late, it exposes the patient to a risk of tumor progression or complications [24].

Table 1: Main tumor markers according to the histological type of ovarian tumor and their possible physiological variations during pregnancy.

The optimal time for surgery is during the second trimester (16–20 weeks of gestation), when organogenesis is complete, luteal function is taken over by the placenta, and the risk of fetal loss is lower [24].

Laparoscopic surgery is possible but requires specific expertise: limited duration (90–120 min), low abdominal pressure, open introduction, and trocars adapted to the gestational age [24]. Although it offers benefits (reduced blood loss, shorter hospital stay, lower risk of premature delivery [19], some authors nevertheless highlight the potential risks associated with pneumoperitoneum, in particular the diffusion of carbon dioxide into the fetal circulation, which can induce fetal acidosis [23]. If an adnexal mass is discovered incidentally during a cesarean section, its removal is recommended [12]. Surgical staging may include appendectomy, infracolic omentectomy, peritoneal biopsies, and lymph node dissection, but postpartum restaging is sometimes necessary [24]. For advanced cancers, optimal cytoreductive surgery is usually postponed until after delivery [19].

Chemotherapy plays a central role, either as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. Its use is only possible from the second trimester onwards, once organogenesis is complete [24]. The recommended first-line agents are paclitaxel and carboplatin, which have the best maternal-fetal tolerance profile and proven efficacy [19]. However, the transplacental passage of many molecules remains a problem, and certain treatments such as bevacizumab or PARP inhibitors must be prohibited [25].

Figure 1: Decision algorithm for the management of malignant ovarian tumors during pregnancy according to histological type and gestational age.

Obstetric monitoring of pregnancies exposed to chemotherapy requires close ultrasound surveillance, including assessment of fetal growth, amniotic fluid, cervical length, and Doppler flow, particularly maximum systolic velocity in the middle cerebral artery, which is useful for detecting anemia or intrauterine growth retardation [25]. Fetal outcomes reported in the literature show increased risks of premature delivery, often iatrogenic, and intrauterine growth restriction, but no net increase in malformations [7]. Where possible, delivery should be delayed beyond 37 weeks of gestation in order to limit neonatal morbidity associated with prematurity [24]. In the event of premature birth, the administration of corticosteroids for lung maturation is recommended [19]. Pathological examination of the placenta is essential, as some transplacental metastases have been described [22].

Regarding prognosis, the literature suggests that pregnancy does not significantly alter the progression of ovarian tumors [18]. Stage and histological type remain the main determinants, as in the general population.

Our observation illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties posed by this rare situation, particularly in advanced cases with peritoneal carcinomatosis. The choice of neoadjuvant treatment combining paclitaxel and carboplatin, followed by a planned delivery and totalization surgery, is in line with current recommendations aimed at reconciling oncological imperatives and maternal-fetal protection.

Conclusion

The prognosis depends heavily on the stage and histological type of the tumor [4–6]. While some forms, particularly those diagnosed early, have a good survival rate (estimated at between 72% and 90% at 5 years) [15,16], advanced forms with peritoneal carcinomatosis continue to have a poorer prognosis, requiring multidisciplinary discussion.

References

- Van Calsteren K., Heyns L., De Smet F., Van Eycken L., Gziri MM., et al. Cancer during pregnancy: Analysis of 215 patients emphasizing the obstetrical and the neonatal outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:683–689. [PubMed.]

- Voulgaris E., Pentheroudakis G., Pavlidis N. Cancer and pregnancy: A comprehensive review. Surg. Oncol. 2011;20:e175–e185. [PubMed.]

- Smith L.H., Danielsen B., Allen M.E., Cress R. Cancer associated with obstetric delivery: Results of linkage with the California cancer registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1128–1135. [PubMed.]

- Korenaga TK., Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;157:799–809. [PubMed.]

- Antonelli NM., Dotters DJ., Katz VL., Kuler JA. Cancer in pregnancy: A review of literature. Part 1. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1996;51:125–134. [PubMed.]

- Mukhopadhyay A., Shinde A., Naik R. Ovarian cysts and cancer in pregnancy. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;33:58–72. [PubMed.]

- Leiserowitz GS., Xing G., Cress R., Brahmbhatt B., Dalrymple J.L., et al. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: How often are they malignant? Gynecol. Oncol. 2006;101:315–321. [PubMed.]

- Boussios S., Moschetta M., Tatsi K., Tsiouris A.K., Pavlidis N. A review on pregnancy complicated by ovarian epithelial and non-epithelial malignant tumors. J. Adv. Res. 2018;12:1–9. [PubMed.]

- Giuntoli R.L., Vang R.S., Bristow R.E. Evaluation and management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;49:492–505. [PubMed.]

- Oehler M.K., Wain G.V., Brand A. Gynaecological malignancies in pregnancy: A review. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003;43:414–420. [PubMed.]

- Grimm D., Woelber L., Trillsch F., et al. Clinical management of epithelial ovarian cancer during pregnancy. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50:963–971. [PubMed.]

- Bruegl A.S., Joshi S., Batman S., Weisenberger M., et al. Gynecologic cancer incidence and mortality among American Indian/Alaska Native women in the Pacific Northwest. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020;1996–2016. [PubMed.]

- Shioka SI., Hayashi T., Endo T., Baba T., et al. Advanced Epithelial ovarian carcinoma during pregnancy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12(5):375–378. [PubMed.]

- Morice P., Uzan C., Gouy S., Verschraegen C., Haie-Meder C. Gynaecological cancers in pregnancy. Lancet. 2012;379(9815):558–569. [PubMed.]

- Botha M., Rajaram S., Karunaratne K. Figo cancer report 2018. Cancer in pregnancy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018;143:137–142. [PubMed.]

- Zhao XY., Huang HF., Lian LJ., Lang JH. Ovarian cancer in pregnancy: A clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases and review of the literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2006;16:8–15. [PubMed.]

- Salani R., Billingsley C., Crafton S. Cancer and pregnancy: An overview for obstetricians and gynecologists. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;211:7–14. [PubMed.]

- Sarandakou A., Protonotariou E., Rizos D. Tumor markers in biological fluids associated with pregnancy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007;44:151–178. [PubMed.]

- Kanal E., Barkovich AJ., Bell C., et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(3):501–530. [PubMed.]

- Han S.N., Lotgerink A., Gziri MM., Van Calsteren K., et al. Physiologic variations of serum tumor markers in gynecological malignacies during pregnancy: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2012;10:86. [PubMed.]

- Fruscio R., de Haan J., Van Calsteren K., Verheecke M., Mhallem M., et al. Ovarian cancer in pregnancy. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017;41:108–117. [PubMed.]

- Forstner R., Thomassin-Naggara I., Cunha TM., Kinkel K., et al. ESUR recommendations for MR imaging of the sonographically indeterminate adnexal mass: An update. Eur. Radiol. 2017;27:2248–2257. [PubMed.]

- Kal HB., Struikmans H. Radiotherapy during pregnancy: Facts and fiction. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:328–333. [PubMed.]

- Dłuski DF., Mierzyński R. Poniedziałek-Czajkowska E Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B. Ovarian Cancer and Pregnancy - A Current Problem in Perinatal Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel). 2020;16:12(12):3795. [PubMed.]

- Minig L., Otaño L., Diaz-Padilla I., Alvarez Gallego R., Patrono MG., et al. Therapeutic management of epithelial ovarian cancer during pregnancy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2013;15(4):259–264. [PubMed.]