>Corresponding Author : Benhadouga Khadija

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 5 | Issue : 6

>Received Date : 30 June, 2025

>Accepted Date : 10 July, 2025

>Published Date : 14 July, 2025

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500128

>Citation : Benhaddouga K, Fatima ZC, Elhodaigui N, Monkid H, Assal A, et al. (2025) Incomplete hydatidiform mole: a case report. J Case Rep Med Hist 5(6): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500126

>Copyright : © 2025 Benhadouga K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access | Full Text

1Resident Physician, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, at Ibn Rochd University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

2Professor in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the Ibno Rochd University Hospital in Casablanca, Morocco

*Corresponding author: Benhadouga Khadija, Resident Physician, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, at Ibno Rochd University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

Abstract

Abdominal pregnancies account for less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies, with a maternal mortality rate that remains eight times higher than for tubal pregnancies. Two types of abdominal pregnancy can occur: primary intra-peritoneal and secondary: expulsion into the abdomen of a pregnancy initiated in a uterine tube (tubo-abdominal abortion). Several risk factors described in the literature are at the origin of ectopic pregnancies, including genital infections in the first instance, infertility as well as intra-uterine device and IVF. In addition to targeted 1st trimester ultrasonography, the deployment of MRI enables us to improve diagnosis and assess the degree of placental adhesion. As for clinical assessment of the parturient, clinical features to look for in an abdominal pregnancy include easy palpation of the fetal parts, abdominal tenderness, atypical fetal presentation and decreased uterine height (IUGR or decreased amniotic fluid). Abdominal pregnancy always carries a high risk of maternal morbidity and mortality, the most dreaded complication being haemorrhage. Nevertheless, the decision to remove the placenta or leave it in situ must be considered on a case-by-case basis, after evaluation of the implantation site. In both cases, the placenta has been completely removed, with hemostasis assured, which justifies the need for no further treatment.

Keywords: Abdominal Pregnancy, Tubal Pathology; Uterine Myoma

Abbreviations: MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging, GA: Gestational Age

Introduction

An abdominal pregnancy is defined as a variety of ectopic pregnancy in which implantation and development of the egg take place partly or entirely in the peritoneal cavity. It can be:

• Primitive: the egg implants immediately in the abdominal cavity.

• Secondary: the egg implants in the abdominal cavity

following: tubo-abdominal abortion, uterine breach, ovarian pregnancy.

This gravidic pathology represents a rare variety in developed countries, but remains the prerogative of countries with a deficient medical and social infrastructure. Abdominal pregnancy is not always easy to diagnose clinically, the sometimes elusive nature of the clinical picture means that further tests are essential.

Case Report

The patient was 30 years old, GI 0P, with no particular pathological history. Her history of illness dates back to January, with the appearance of a single episode of low-abundance bleeding, the onset of acute pelvic pain in the right iliac fossa, and a delayed menstrual period of 12 weeks of amenorrhea and 2 days.

Clinical examination: patient hemodynamically and respiratory stable, conjunctiva normo-colored, tenderness in right iliac fossa, uterus increasing in size, cervix normal in appearance, no bleeding.

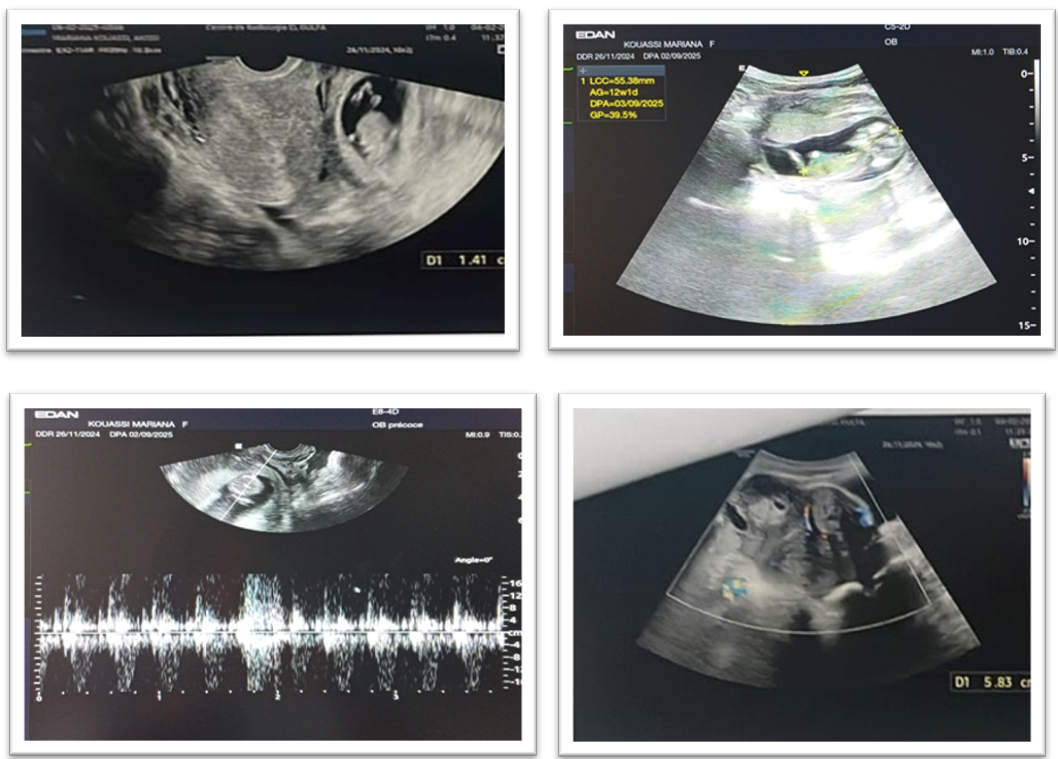

On pelvic ultrasound: enlarged uterus with large anterior corporal intramural myoma measuring 45 x 43 mm classified FIGO 6 (figure 2), endometrium of normal thickness, thin vacuity line in place. Presence of a 100 x 53 mm heterogeneous tissue formation above and laterally on the right uterus, seat of a fetus corresponding to a pregnancy of 11 weeks' amenorrhea with a good trophoblastic reaction (figure 1), good cardiac and fetal activity ,Both ovaries seen with normal appearance ,Fairly large pelvic effusion. The B HCG level : 30156 m IU/mL.

Figure 1: Intra-abdominal ectopic pregnancy, LCC 55.38 mm

Figure 2: Anterior corporal intramural myoma measuring 45 x 43 mm classified FIGO 6

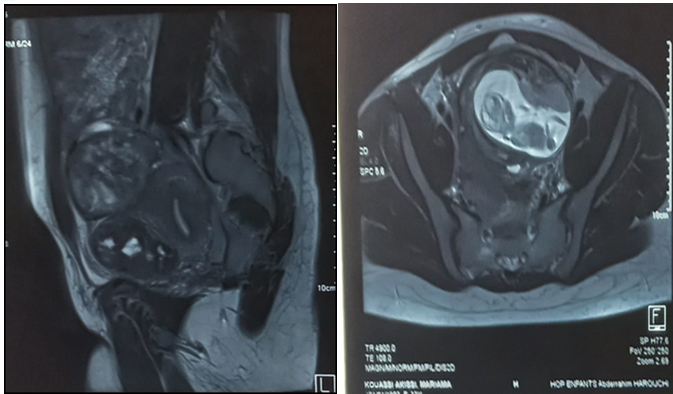

On Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): enlarged uterus measuring 9 cm, latero-deviated on the right with free uterine cavity of normal morphology; small hemoperitoneum of anterior cysteometrial appearance and subserosal formation, measuring 65x4.1 . Uterine myoma classified FIGO 6; remodeled. Presence of a gestational sac above and laterally on the left uterus, containing an embryo with a good decidual reaction, in intimate contact with the homolateral ovary with no separation line (figure 3).

Figure 3: Intra-abdominal ectopic pregnancy

Exploration

Small effusion, multiple parieto-hepatic and utero-epiploic adhesions, 6cm anterior isthmic subereal myoma.

Spherical right adnexa adherent to posterior wall of uterus.

Abdominal ectopic pregnancy adherent to digestive and parietal structures and left adnexa.

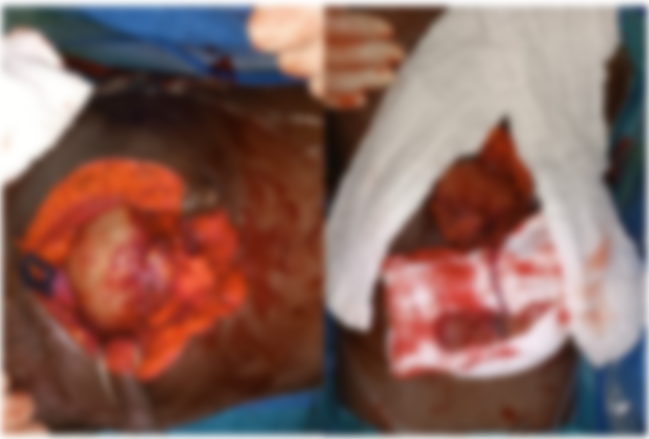

Adhesiolysis, pregnancy evacuation, left salpingectomy and myomectomy (Figure 4-5-6).

Figure 4-5: Abdominal ectopic pregnancy

Figure 6: Surgical parts

Discussion

Over the last two decades, the rate of ectopic pregnancy has almost doubled or tripled, reaching 1.6% to 2% of all pregnancies [1,2]. In 98% of cases, the pregnancy is tubal, 0.5% ovarian and 1.5% abdominal the extreme frequencies of abdominal pregnancies (GAS) before been reported in various countries around the world range from 1/1,100 to 1/50820 GA per delivery.

The mother's age has sometimes been incriminated as a factor favoring GA. However, it does not seem to be a very important factor. Some believe that the mother's advanced age does not play a direct role, but rather increases the duration of exposure to sexually transmitted diseases [3,4].

Racial predominance is reported by some authors, with the incidence in the black race 10 to 25 times higher than in the white race [5]. This frequency has more to do with the high incidence of tubal pathology in the black population than with racial predominance per se: the frequency of tubercular, bilharziosis and venereal tubal lesions in the African environment provide the breeding ground for G.A., while under-medication does the rest, being responsible for the absence of G.A. diagnosis.

These are generally pauci parous women [6,7], and some authors believe that the frequency of GA is higher during the first and second pregnancies, but the small numbers involved make these results questionable.

In 1990, Martin et al. proposed a new classification based on gestational age (GA) and location of ovarian implantation, thus distinguishing early GA whose GA is less than 20 weeks' amenorrhea with trophoblastic implantation which takes place on the uterus, the broad ligament, the parietal peritoneum or the DOUGLAS cul-de-sac [1,8], as well as the liver, spleen, gallbladder and diaphragm [6,9]. Most women will present in a state of hypovolaemic shock, the result of vascular ruptures at the implantation site, and late GA corresponding to a GA of over 20 weeks' amenorrhoea [1,10]. Here, the problem of fetal viability arises, which becomes possible from 24 to 26 weeks of evolution. In the case of advanced GA, the placental implantation zone is of good quality, allowing the pregnancy to continue. In this case, the placenta implants on the uterus, broad ligament, douglas, colon and epiploic apron.

Diagnosis of GAD is not always easy [10,11], and questioning must be methodical and meticulous. The clinical examination is crucial and highly suggestive, especially in cases of advanced G.A., provided that it is considered [12,13].

A value >10 mUL / ml confirms the gravidic state, but does not give any indication of the location of the pregnancy. An abnormally high HCG level, especially when associated with an empty uterus, suggests the diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy.

Ultrasound: is of capital value in diagnostic orientation, and is currently considered to be the examination of choice for the diagnosis of GA.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Harmless and three-dimensional, it has been used for diagnostic purposes as well as for monitoring placental involution. The data collected have made it possible to define the exact ratios of the fetus, placenta and uterus [12,13].

Treatment of GA is solely surgical, with the aim of ensuring fetal rescue without compromising maternal prognosis. The child must therefore be extracted and the placenta removed if possible, after assessing the risk of haemorrhage [12].

The ideal approach is a median laparotomy under the umbilicus, extending more or less beyond the umbilicus to allow adequate exploration of the lesser pelvis and abdominal cavity. Extraction of the fetus is often straightforward because of its anterior position, after careful detachment of the intestinal loops and epiploic adhesions, and after opening of the ovarian sac if present, with ligation of the cord closest to the placenta. Removal of the placenta, whenever possible, is the preferred approach for rapid healing and simple post-operative management. However, care must be taken, otherwise there is an immediate risk of massive, sometimes uncontrollable, sheet-like haemorrhage, and it is therefore necessary to study the extension of the placenta, which can only be correctly assessed in the open abdomen, after opening and extraction of the fetus prior to removal of the placenta.

Conclusion

At the end of this study, through these cases of abdominal pregnancies and literature review. We were able to draw certain conclusions: Two types of abdominal pregnancy can be distinguished: Primitive GA: where the egg implants in the abdominal cavity. Secondary GA: more frequent, where the egg develops in the abdominal cavity following a uterine breach, a tubo-abdominal abortion or an ovarian pregnancy. This type of pregnancy is exceptional in medicalized countries, but its frequency is higher in under-medicalized countries, due to an increase in risk factors, including high or low genital infection, a history of abortions and curettages, and the possible use of ovulation inducers. We note that symptomatology is polymorphic and clinical signs inconstant, and are only of value if the probability of an abdominal pregnancy has been evoked. The diagnosis will be confirmed by further investigations: Abdominal ultrasound: the only way to confirm a uterine vacuity and detect a fetus outside the uterus. MRI and CT seem to be the examinations of the future: on the one hand, they confirm the diagnosis reported by ultrasound; on the other hand, they allow us to study placental extension and follow the evolution. In terms of treatment, intervention should be immediate if the fetus is viable, or if the diagnosis is made before 5 months of pregnancy. Interversion should be postponed if viability is close, if the child has no sonographically visible deformities, if the pregnancy is well supported and if maternal and fetal monitoring is assured. In the event of fetal death, we wait 4 to 8 weeks before intervening. Depending on the case, the placenta may be removed or left in the abdomen. Chemotherapy in the latter case is reserved for cases of dangerous placental insertion, and for cases where choriocarcinoma is feared.

Reference

- Atraish HK., Friiedae A., Hogue CJR. Abdominal pregnancy in the United States:frequency and maternal, orbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;68:333‒7. [PubMed.]

- Perasad PS., Dwaraikanaith LS. Disregarding clinical features leads to misdiagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;174:296‒7. [Ref.]

- Mooenenia Delarue MWG., Haeist JWG. Ectopic pregnancy three times in line of which two advanced abdominal pregnancies Eur J Obstet. 66(1):87-8. [PubMed.]

- Abossolo T., Sommaer JC., Dancoisne P., Orivaini E., Tuaillona J., Isoaard L. Grossesse abdominale du premier trimestre et traitement coeliochirurgical. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 1998;23:676‒8. [Ref.]

- Deshpandae N., Maters A., Achariya U. Broad ligament twin pregnancy following in vitro fertilization Hum Reprod. 2000;14‒3:852‒4. [PubMed.]

- Martini Jr JN., Sessumis JK., Martin RW. Abdominal pregnancy current concepts of management. Obstet Gynecole. 1999;71:549‒57. [PubMed.]

- Hreshichyshyna MM., Bogeni B., Loughran CH. What is the actual present‒day management of the placenta in late abdominal pregnancy? Analysis of 101 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;81‒2:302‒17. [PubMed.]

- Luadwiaa.,g M., Kaisia M., Bauer O., Dieodrich K. The forgotten child A case of heterotopic., intra‒abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term Hum Reprod. 2001;14‒5:1372. [PubMed.]

- Echeanique‒Elizoando M., Carabonero K. Full term abdominal pregnancy., mother and infant survival JAmColl Syrg. 2001;231:192‒192. [Ref.]

- Luadwiaa M., Kaisia M., Bauer O., Dieodrich K. The forgotten child A case of heterotopic., intra‒abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term Hum Reprod. 2001;14‒5:1372‒4. [PubMed.]

- Delkel I., Veridiano NP., Tainaacer ML. Abdominal pregnancy review of current management and addition of ten cases Obstet Gynecol. 1988;60:200‒3. [PubMed.]

- Sfari E., Kaabar H., Marrakechi O., Zouari F chealli H., Kharoufm., et al. La grossesse abdominale., entité anatomoclinique rare A propos de quatre cas (19811990). Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1999;88‒4:261‒5. [Ref.]

- Bajoa JM., Garcia‒Frutoiis A., Huertas A. Sonographic follow‒up of a placenta left in situ after delivery of the fetus in an abdominal pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:285‒8. [PubMed.]