>Corresponding Author : Michael L Levy

>Article Type : Short Report

>Volume : 5 | Issue : 2

>Received Date : 21 Feb, 2025

>Accepted Date : 05 March, 2025

>Published Date : 8 April, 2025

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500110

>Citation : Crawford J, Jandial Z, Narang P and Levy ML. (2025) Traditional Ethnobotanical Treatments in Bolivia. J Case Rep Med Hist 5(2): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2500110

>Copyright : © 2025 Crawford J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Short Report | Open Access | Full Text

1.Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA, USA

2.University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

3.University of California, Berkeley - University of California San Francisco Joint Medical Program, Berkeley, CA, USA

4.Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, CA, USA

*Corresponding author: Michael L Levy, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, CA, USA

Abbreviations: CNS: Central Nervous System, LMICS: Low-And-Middle-Income Countries, AEDS: Antiepileptic Drugs, TG: Treatment Gap, HICS: High-Income Countries

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic and disabling disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) that affects approximately 70 million people worldwide, with the majority residing in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) [1]. In LMICs, the epilepsy treatment gap (TG) – defined as the proportion of people with epilepsy who require but do not receive treatment – often exceeds 75%. This gap is attributed to multiple factors, including under-resourced healthcare systems, inadequate access to trained medical professionals, limited availability and affordability of antiseizure medications, transportation barriers, and pervasive sociocultural stigmas [2,3]. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the primary therapeutic options for managing epilepsy in high-income countries (HICs), but in many LMICs, traditional remedies continue to play a significant role in many communities due to their relative affordability, distrust of biomedical interventions, and cultural preferences for traditional healing practices [4].

In Bolivia, traditional remedies – often referred to as ethnobotanical treatments – have historically played a significant role in primary healthcare and are deeply rooted in local cultural contexts and indigenous traditions [5]. Approximately 40% of the population over the age of 15 identify as indigenous [6]. Many communities maintain close relationships with their natural environment and possess unique traditional knowledge, including the use of specific medicinal herbs [7]. These plants are widely utilized in rural and urban areas, such as La Paz and El Alto, where dedicated stalls selling medicinal plants are common.

Ethnobotanical treatments, and the underpinning traditional knowledge, are central to the identities, cultures, languages, heritage, and livelihoods of many communities. This knowledge has been transmitted across generations through apprenticeship, storytelling, songs, dances, carvings, paintings, and performances. It is embedded in rituals, symbols, myths, and social institutions. However, these rich traditions face increasing threats of erosion and disappearance. [8,9]. Drivers of this decline include deforestation, dispossession, discrimination, and the displacement of these communities from their ancestral territories [10]. Furthermore, trends in education, urban migration, religion, and the politicization of rural unions have further curtailed opportunities for intergenerational dialogue and the transmission of traditional medicinal knowledge [8].

Research on changes in community attitudes towards traditional healers as well as medical doctors and medicinal herbs since the COVID-19 pandemic remains limited. Nearly a decade prior to the pandemic, however, national surveys by the Ministry of Health indicated that 60% of Bolivians relied on natural prescriptions before seeking treatment from a “modern physician [11]. It has been suggested that, in some regions, this preference for traditional remedies was reinforced or revitalized during the pandemic. Communities turned to medicinal herbs to minimize the need to seek care in urban regions with high COVID-19 transmission rates and due to shortages of medications, healthcare providers, and hospital services [6].

Increasingly efforts are being dedicated to documenting and preserving knowledge about medicinal plants [12,13]. Although some studies have been criticized for being oversimplified or outdated, past investigations predominantly explore natural remedies for musculoskeletal ailments (e.g. joint pain, sprains, swelling, bone fractures, etc.), urological ailments, digestive ailments (e.g. diarrhea, stomach aches), pregnancy-related concerns, and more. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, medicinal herbs for neurological conditions such as epilepsy have been underexplored. It is unclear whether this is due to a cultural preference for non-plant-based traditional remedies for epilepsy treatment, sociocultural and economic barriers that limit accessibility and acceptability, or simply an evidence gap from prior investigations. To that end, the aim of this brief review is to explore medicinal herbs historically used to manage epilepsy in Bolivia and provide insight into traditional healing customs.

Methods

To identify traditional remedies, particularly ethnobotanical treatments, utilized in Bolivia for epilepsy, a literature search from PubMed and ScienceDirect was performed to identify research articles published prior to December 2023. The keywords for the search included a combination of the following terms: traditional medicinal herbs, ethnobotanical treatments, herbal antiepileptic and/or anticonvulsant, Bolivia, Kallawayas, traditional medicinal knowledge, botanicals + epilepsy. References of articles were manually checked to prevent eligible research from being omitted. Information delineating these ethnobotanical treatments’ medical indication, vernacular names, plant parts utilized, mode of preparation, means of remedy administration, and more recent investigations assessing their therapeutic potential were compiled. Approximately forty articles were identified within this scope. Major themes included the history of traditional medicinal healing in Bolivia and the broad variety of traditional medicinal herbs used for a range of conditions; information regarding herbs used for neurological conditions, particularly for epilepsy, was limited.

Traditional Healers in Bolivia

Exploring traditional remedies and ethnobotanical treatments in Bolivia requires an appreciation of the broader context of traditional healing and the role of healers. For years, efforts have been underway across Bolivia to integrate the practices of medical doctors and traditional healers. Among the most renowned traditional practitioners are the Kallawaya, a community of healers who treat ailments with herbs and rituals that originate from pre-Incan times.

The Kallawaya possess a vast pharmacopeia of minerals, animals, and plants, encompassing an estimated 980 species [14]. Of these, they commonly employ over 300 plants. As itinerant healers, the Kallawaya have historically traveled throughout Bolivia and neighboring countries, such as Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, reaching as far as Panama during the construction of the Panama Canal [13]. Their tradition represents over 1,000 years of medicinal expertise, and it has been suggested that the Kallawayas performed brain surgery as early as 700 A.D. using Ilex guayusa, a caffeinated holly tree [14].

The Kallawaya share a principal belief that human beings should respect Mother Earth and live in harmony with their environment [15]. Some Kallawaya healers reside permanently in major cities such as La Paz, where they offer herbal therapies and rituals in consulting rooms; others follow patterns of itinerant medical practice, spending at least half of the year outside their home communities [16]. They also reside in the high-altitude, mountainous regions of Bautista Saavedra north of La Paz [17].

The Kallawaya are often recognized for traveling in pairs, including a master healer and an apprentice. They speak Quechua, Spanish, and Aymara, but their knowledge and skills have been historically passed on through successive generations through Machai Juyai, a special language used in prayers and ceremonies. In recent years, several leaders have integrated into social networks and professional organizations and have served to lobby in defense of cultural rights, mediating contact between their communities and NGOs, foreign investigators, and the Bolivian government. In these roles, they oversee the dissemination of their expertise and medical practice through educational activities such as the issuing of professional certificates, work licenses, and identification cards.

Medicinal Herbs with Potential Anticonvulsant Properties

Our literature search, centered on the aforementioned key terms and ethnobotanical treatments employed by the Kallawayas, revealed a lack of research on traditional medicinal herbs used specifically for epilepsy treatment in Bolivia. One notable study, based on semi-structured interviews with medicinal herb sellers in La Paz and El Alto, documented medicinal information for approximately 129 plant species applied to over 90 general medicinal indications. Among these, seven species were identified as being used to treat dizziness and headaches and five species were identified as “nervous tranquilizers.”

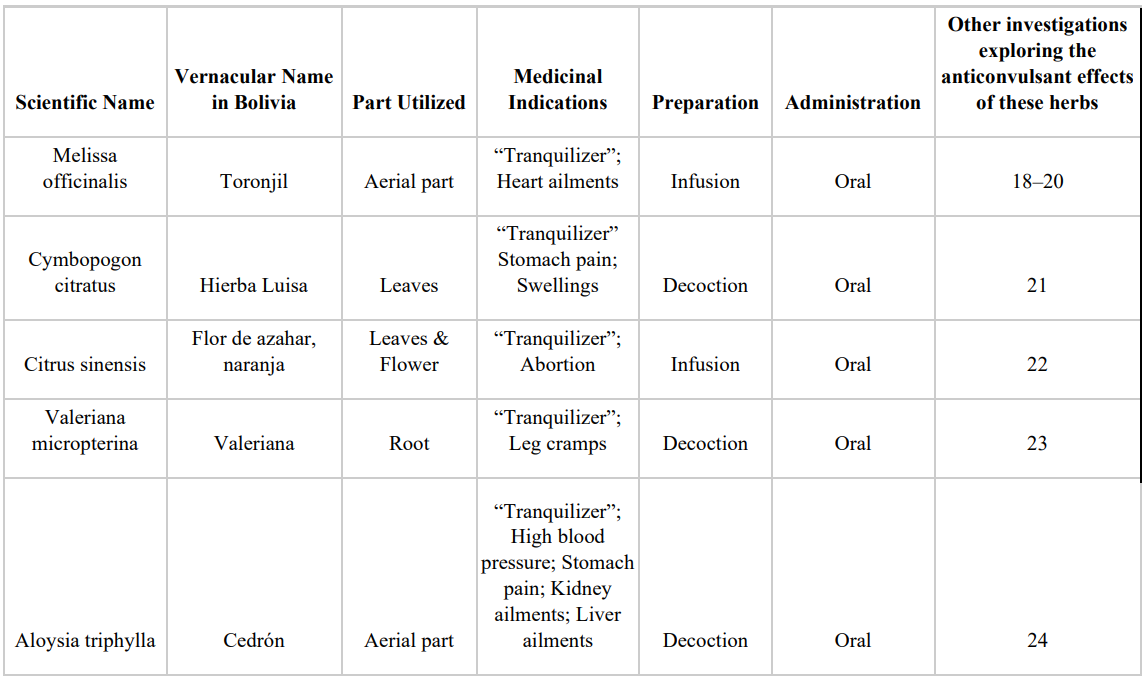

We hypothesize that these five herbs (Table 1) may have been historically or contemporarily utilized in epilepsy treatment; however, this remains speculative. Our hypothesis is informed by other studies appraising these herbs for their purported anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, antidepressant, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive, antispasmodic, and antiepileptic properties. Nonetheless, direct evidence of their use for epilepsy in Bolivia is lacking and warrants further investigation. The limited biochemical characterization of these herbal medicines presents an opportunity to investigate their metabolic constituents, particularly for compounds that modulate sodium channels or enhance GABAergic signaling.

Table 1. Medicinal herbs possibly used for epilepsy

Discussion

From our perspective, given the significant burden, high incidence, and persistent TG of epilepsy in Bolivia [25], it is crucial to understand the barriers preventing patients with epilepsy from accessing care, the availability of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic options, and the influence of cultural beliefs on treatment adherence. We previously described the impact of the implementation of the Unified Healthcare System on pediatric epilepsy management in La Paz, Bolivia and highlighted the pervasive belief in the healing properties of bat blood for treating seizures, which has driven the illegal sale of over 3,000 bats each month [26,27]. This investigation aimed to identify alternative traditional remedies for epilepsy, particularly ethnobotanical treatments. However, to the best of our knowledge, the use of medicinal herbs for epilepsy treatment and management in Bolivia remains largely unclear and warrants further investigation. The identification and use of medicinal plants, as well as specific ritual practices, are considered traditional proprietary knowledge, essential not only to the Kallawaya’s expertise but also to their livelihoods. Recognizing this, we have approached this review with the utmost respect for the Kallawaya tradition and the communities who safeguard this knowledge.

References

- World Health Organization. Epilepsy. 2024. [Ref.]

- Saxena S., Li S. Defeating epilepsy: A global public health commitment. Epilepsia Open. 2017;2:153–5. [PubMed.]

- Nicoletti A., Todaro V., Cicero CE., Giuliano L., Zappia M., Cosmi F., et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on frail health systems of low- and middle-income countries. The case of epilepsy in the rural areas of the Bolivian Chaco. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;118:107917. [PubMed.]

- Beltrão ICSL de., Carneiro YVA., Delmondes G de A., Lima Junior L de B., Kerntopf MR. Concepts, beliefs, and traditional treatment for childhood seizures in a quilombola community in northeastern Brazil: Analysis by the Discourse of the Collective Speech. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1875. [PubMed.]

- Vandebroek I., Calewaert JB., De jonckheere S., Sanca S., Semo L., Van Damme P., et al. Use of medicinal plants and pharmaceuticals by indigenous communities in the Bolivian Andes and Amazon. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:243–50. [PubMed.]

- Bolivia. Indigenous Navigator. [Ref.]

- Macía MJ., García E., Vidaurre PJ. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants commercialized in the markets of La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:337–50. [PubMed.]

- Gruberg H., Dessein J., D´Haese M, Alba E., Benavides JP. Eroding traditional ecological knowledge. A case study in Bolivia. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J. 2022;50:1047–62. [Ref.]

- Reyes-García V., Guèze M, Luz AC., Paneque-Gálvez J., Macía MJ., Orta-Martínez M., et al. Evidence of traditional knowledge loss among a contemporary indigenous society. Evol Hum Behav. 2013;34:249–57. [PubMed.]

- Yong E. Loss of traditional knowledge in the Amazon leads to poorer child health. National geographic. 2008. [Ref.]

- Minority Rights Group International. State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2013 – Case study: Bolivia: Traditional healers and climate change. 2013. [Ref.]

- Poblete EO. Plantas Medicinales de Bolivia: Farmacopea Callawaya. 1969;529. [PubMed.]

- Bastien JW. Pharmacopeia of Qollahuaya Andeans. J Ethnopharmacol. 1983;8:97–111. [PubMed.]

- Tracy L. Barnett and Hernán Vilchez. The Kallawaya: Doctors of the Inka. The Esperanza Project. 2023. [Ref.]

- Chelala C. Health in the Andes. Traditional medicine in the modern world. Meer. 2022. [Ref.]

- Callahan M. Signs of the time: Kallawaya medical expertise and social reproduction in 21st century Bolivia.UM Library. 2011. [Ref.]

- Andean cosmovision of the Kallawaya. UNESCO. [Ref.]

- Shakeri A., Sahebkar A., Javadi B. Melissa officinalis L. - A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and. pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;188:204–28. [PubMed.]

- Gorgich E., Komeili G., Zakeri Z., Ebrahimi S. Comparing anticonvulsive effect of Melissa officinalis` hydro-alcoholic extract and phenytoin in rat. Health Scope. 2012;1:44–8. [Ref.]

- Jalal Uddin Bhat., Qudsia Nizami., Mohammad Aslam., Asia Asiaf., Shiekh Tanveer Ahmad., and Shabir Ahmad Parray. Antiepileptic activity of the whole plant extract of melissa officinalis in swiss albino mice. 2012;886–889. [Ref.]

- Hacke ACM., Miyoshi E., Marques JA., Pereira RP. Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf, citral and geraniol exhibit anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in zebrafish. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;275:114142. [PubMed] [PubMed.]

- Citraro R., Navarra M., Leo A., Donato Di., Paola E., Santangelo E., et al. The anticonvulsant activity of a flavonoid-rich extract from orange juice involves both NMDA and GABA-benzodiazepine receptor complexes. Molecules. 2016;21:1261. [PubMed.]

- Kapucu A., Ustunova S., Akgun-Dar K. Valeriana officinalis extract and 7-Nitroindozole ameliorated seizure behaviours, and 7-Nitroindozole reduced blood pressure and ECG parameters in pentylenetetrazole-kindled rats. Pol J Vet Sci. 2020;23:349–57. [PubMed.]

- Bahramsoltani R., Rostamiasrabadi P., Shahpiri Z., Marques AM., Rahimi R., Farzaei MH. Aloysia citrodora Paláu (Lemon verbena): A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;222:34–51. [PubMed.]

- Bruno E., Quattrocchi G., Crespo Gómes EB., Sofia V., Padilla S., Camargo M., et al. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy associated with convulsive seizures in rural Bolivia. A global campaign against epilepsy project. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139108. [PubMed.]

- Zain Jandial., Pranay Narang., Jorge Daniel Brun Aramayo., John Crawford., and Michael L.Levy. Barriers to Pediatric Epilepsy Care at Hospital Del Nino in La Paz, Bolivia, and Traditional-Medicine-Alternatives. Journal of Neurology and Critical Care. 2023;2(1). [Ref.]

- Dennis Lizarro., Galarza MI., Aguirre LF. Tráfico y Comercio de Murciélagos en Bolivia. Research Gate. 2010. [Ref.]