>Corresponding Author : Dorsaf Elinkichari

>Article Type : Case Report

>Volume : 4 | Issue : 5

>Received Date : 28 Feb, 2024

>Accepted Date : 11 March, 2024

>Published Date : 14 March, 2024

>DOI : https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2400121

>Citation : Elinkichari D, Tantot J and Dalle S. (2024) Pembrolizumab-Induced Lichen Planus in a Patient with Metastatic Pulmonary Giant Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Case Rep Med Hist 4(5): doi https://doi.org/10.54289/JCRMH2400121

>Copyright : © 2024 Elinkichari D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Report | Open Access | Full Text

1Service de Dermatologie, CHU Lyon Sud, Pierre bénite, Lyon, France

2Service d’Anatomopathologie, CHU Lyon Sud, Pierre bénite, Lyon, France

*Corresponding author: Dorsaf Elinkichari, Service de Dermatologie, CHU Lyon Sud, Pierre bénite, Lyon, France

Abstract

Ιmmune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized the management of advanced cancers. Nevertheless, the oncologic response is often achieved at the cost of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). We present a case of an immune-mediated lichen planus (LP) and a literature review of similar cases.

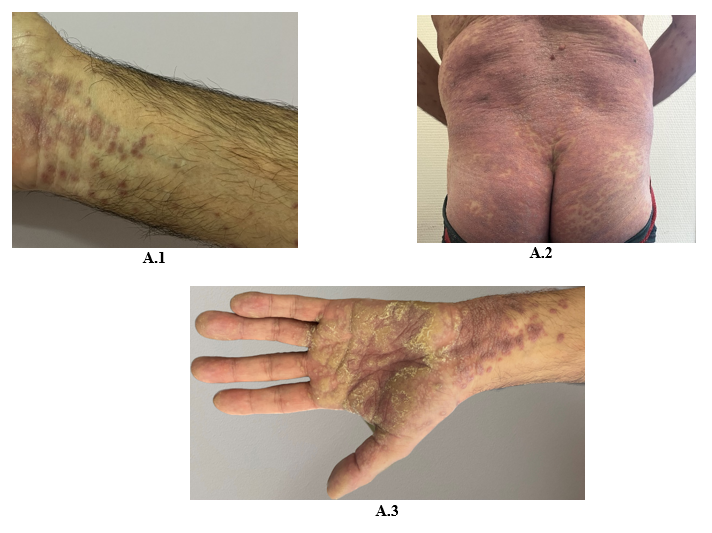

A 60-year-old man, who is being treated with pembrolizumab for a pulmonary giant cell carcinoma since April 2022, presented in November 2022 with a pruritic eruption that appeared two weeks ago. Examination showed bright purple confluent scaly papules on wrists, proximity of limbs, back and buttocks and palmar keratoderma made of violaceus papules covered with reticular white striae. Histological examination revealed an epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolization of the basal layer, necrotic keratinocytes and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with many eosinophils. The diagnosis of an immune-related LP was retained. Pembrolizumab was withheld because of the severity and the extension of the lesions. Superpotent topical steroids were prescribed with a significant improvement of the rash within 3 weeks.

Immune-mediated lichenoid euptions represent one of the most frequent dermatologic irAEs. In our patient, the onset seven months after the initiation of ICIs, the infiltrate rich in eosinophils, and the rapidly diffused character are indications of an immuno-mediated LP.

Keywords: Lichen planus; Pembrolizumab; Anti-PD1; Immunotherapy; Drug reactions

Abbreviations: ICI: Ιmmune checkpoint inhibitors, LP: lichen planus

Introduction

Ιmmune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized the management of advanced cancers in dermatology as well as in other disciplines [1]. Pembrolizumab is one of the most frequently used ICIs, with a growing list of approved indications including non-small-cell lung cancers, metastatic melanoma, and advanced squamous cell cancer. It is an anti-Programmed Death protein 1 (Anti-PD-1) agent. Blocking the inhibitory signals of cytotoxic T cells, ICIs allow the upregulation of the antitumor immune response [2]. Nevertheless, the immune-mediated oncologic response is often achieved at the cost of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that may potentially affect any organ. Dermatologic irAEs (dirAEs) are among the most common and are observed in about 40% of all treated patients. These include maculopapular, psoriasiform, lichenoid, vitiligoid and eczematous rashes, auto-immune bullous disorders, pruritus, hair, nail and mucosal changes, as well as a few severe life-threatening drug reactions [3].

Herein we describe a case of an immune-mediated lichenoid eruption in a patient being treated with pembrolizumab for a pulmonary giant cell carcinoma.

Case Report

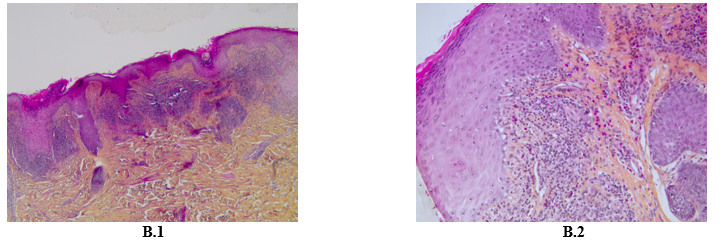

A 60-year-old Caucasian man, with a history of hypothyroidism supplemented for years, and who is being treated with pembrolizumab for a stage IV pulmonary giant cell carcinoma since April 2022, presented in November 2022 with a pruritic eruption that appeared two weeks ago. The eruption started with confluent papules of the wrists then extended to the limbs and the trunk. The patient did not have any other relevant history. Skin examination showed polygonal, bright purple, confluent, and scaly papules on wrists, proximity of limbs, back and buttocks and palmar keratoderma made of violaceus and confluent papules covered with reticular fine whitish streaks (Figure A). These lesions were symmetrically distributed. Mucosal and nail examination was normal. The standard biological tests were within normal values. The patient had no history of unprotected sexual intercourse, and staining for syphilis antibodies was negative. Differential diagnosis included lichen planus (LP) and lichenoid drug eruption. Light microscopic evaluation of skin biopsy of the back revealed histological features of LP: Hypergranulosis, vacuolization of the basal layer with apoptotic keratinocytes, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate. The presence of numerous eosinophils did not rule out the diagnosis of a lichenoid drug reaction (Figure B). The diagnosis of a grade 3 immune-related lichenoid eruption was then retained. A multidisciplinary consultation meeting led to anti-PD-1 therapy withdrawal because of the severity and the extension of the lesions. Superpotent topical steroids were prescribed with a significant improvement of the pruritus and the rash within three weeks. Given the stability of the cancerous disease, checkpoint inhibitors were not reintroduced. At the fourth month follow-up, all skin lesions have healed.

Figure 1: Bright purple confluent scaly papules on wrists (A.1), back and buttocks (A.2), Palmar keratoderma (A.3)

Figure 2: Hematoxylin Eosin Coloration X 10 showing epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolization of the basal layer, band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate (B.1) Hematoxylin Eosin Coloration X 20 showing rich lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate (B.2).

Discussion

LP is a T cell‐mediated, inflammatory skin condition that affects between 0.5 and 1% of the population. Classic LP typically presents as a symmetrically distributed pruritic, polygonal, violaceous papules. It is suggested that the pathogenicity of LP involves the autoimmune-mediated lysis of basal keratinocytes by CD8 + lymphocytes. Yet, definitive etiological triggers are still unknown. An association between LP and the following has been observed : chronic active hepatitis (hepatitis C particularly); primary biliary cirrhosis; complication of hepatitis B vaccination; viral and bacterial antigens; medications; trauma (Koebner phenomenon); metal ions; and some autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis, alopecia areata, vitiligo, and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy [4].

Lichenoid eruptions are among the most frequent manifestations of anti-PD-1 cutaneous toxicity. PD-1 is a membrane receptor. Its activation is responsible for self-tolerance during immune response. Increased expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 by tumour cells thus leads to inhibition of T cells and tolerance toward malignant cells. Blockade of this pathway is transforming the prognosis of many cancers. However, the inhibition of the same pathway may lead to disruption of loss of self-tolerance and induce immune mediated diseases [2]. T cell-mediated autoimmune response secondary to PD-1 inhibition induces cell apoptosis, including basal layer keratinocytes apoptosis, and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of lichenoid reactions.

According to a recent study, LP or lichenoid eruption is 10.7-fold more likely to develop in patients treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab than the general population [5]. Although lichenoid reactions have emerged as an important dirAEs, immune-induced LP have been infrequently described in the literature. So far, 26 cases of LP and 21 cases of LP pemphigoid induced by anti-PD1 have been reported, with the first description appearing in 2016 [6,7]. Among LP cases, 14 patients had a classic form (Cutaneous LP: 7 cases; cutaneo-mucosal LP: 7 cases), seven patients had bullous LP, four patients had hypertrophic LP mimicking early invasive squamous cell carcinomas, one patient had LP pilaris, and one patient had erosive LP [6-12]. The patient with LP pilaris also had lesions of classic cutaneous LP [13]. Delay of onset from the beginning of treatment ranged from two weeks to 18 months [11,12]. A delay of seven months was observed in our patient. This latency period is of particular interest as cutaneous toxicities can present even after withdrawal of ICIs [3]. In the majority of the reported cases, as in our patients, lesions were clinically and histologically indistinguishable from classic LP. However, a consistent chronology, an infiltrate rich in eosinophils and an eruptive and rapidly diffused character may be indicators of an immuno-mediated LP.

The majority of patients were treated with either oral or topical corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine was prescribed, in association with oral prednisone and topical steroids, in one of the patients presenting with a hypertrophic LP, with a complete resolution [14]. In the patient with LP pilaris, anti-inflammatory dose of doxycycline initially slowed the progression. However, control of infammation has been obtained only with systemic steroids and hydroxychloroquine, with a remaining scarring alopecia [13]. Withdrawal of anti-PD-1 treatment was considered in seven patients. Pembrolizumab was temporarly suspended in two patients [15,16]. Cases of LP associated with anti-PD1 are summarized in Table A.

In conclusion, immunotherapy is increasingly becoming the standard treatment for many malignancies. ICIs are actually reshaping the prognosis of many cancers. These new treatments are bringing new hope to patients, but also a whole new spectrum of toxicities for clinicians to manage. Immune-induced LP represents one of the most frequent dirAEs. Several variants have been reported in the literature such as hypertrophic LP, bullous LP, and LP pilaris. However, immune-related classic cutaneous LP is the most frequently described. Treatment is based on topical steroids. Systemic steroids are often proposed in severe reactions. Withdrawal of ICIs may be indicated in refractory cases, in the framework of a multidisciplinary consultation meeting.

Table A: Reported cases of LP associated with anti-PD1

| Age (Years) | Sexe | History of LP before ICIs | Variant of LP | Treatment | Primary disease | Delay from start of treatment to onset of symptoms | Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wakade et al., 2016 [17] | 71 | Female | Unspecified | Bullous LP | Pembrolizumab | non-small-cell lung cancer | 1 month | Topical steroids Acitretin 0.2 mg/kg/d |

| 49 | Female | Unspecified | Bullous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 3 weeks | Withdrawal of ICIs Bolus IV methylprednisone followed by systemic steroids Acitretin 0.2 mg/kg/d | |

| 86 | Male | Unspecified | Bullous LP | Pembrolizumab | non-small-cell lung cancer | 15 weeks | Topical steroids ICIs discontinued (Stable malignancy/Respiratory failure) | |

| Komori et al., 2016 [18] | 67 | Female | Unspecified | Classic cutaneous LP | Nivolumab + Radiotherapy | Breast cancer with hepatic metastasis | Unspecified | Withdrawal of nivolumab Topical steroids |

| Hofmann et al., 2016 [16] | 87 | Male | Unspecified | Classic mucosal LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 48 weeks | Topical steroids Systemic steroids ICIs temporarily suspended |

| 69 | Male | Unspecified | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Pembrolizumab> | Metastatic melanoma | 49 weeks | Topical steroid Systemic steroids Withdrawal of ICIs | |

| 79 | Male | Unspecified | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 49 weeks | Withdrawal of ICIs Topical steroids Systemic steroids | |

| 65 | Female | Unspecified | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 43 weeks | Topical steroids Topical pimecrolimus Mouthwash steroids | |

| 74 | Male | Unspecified | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 49 weeks | Topical steroids Mouthwash steroids | |

| 46 | Male | Unspecified | Classic cutaneous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 24 weeks | Topical steroid Levocetirizine 5 mg/d | |

| 80 | Male | Unspecified | Classic cutaneous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 21 weeks | Topical steroids Levocetirizine 5 mg/d | |

| Komori et al., 2017 [19] | 67 | Female | Unspecified | Erosive LP | Nivolumab + Radiotherapy | Breast cancer with hepatic and lymph node metastasis | 5 months | Topical steroids Systemic steroids |

| Massey et al., 2017 [20] | 70 | Female | Unspecified | Hypertrophic LP | Pembrolizumab | Squamous-cell lung cancer | 3 months | Topical steroids |

| Zhao et al., 2018 [15] | 67 | Man | No | Bullous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 12 months | Topical steroids Systemic steroids ICIs temporarily suspended |

| Biolo et al., 2018 [21] | 77 | Man | Unspecified | Linear bullous LP | Nivolumab | Metastatic renal carcinoma | 8 months | Topical steroids Systemic steroids |

| Maarouf et al., 2018 [22] | 51 | Man | Yes | Hypertrophic LP | Nivolumab | Non-small-cell lung cancer, stage IV | 2 weeks | Topical steroids |

| Fontecilla et al., 2018 [23] | 79 | Man | Yes | Hypertrophic LP | Pembrolizumab | Non-small-cell lung cancer, stage IV | 6 weeks | Systemic steroids |

| Denny et al., 2018 [24] | 46 | Man | No | Classic cutaneous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 6 months | Topical steroids Systemic steroids |

| Coscarat et al., 2020 [13] | 78 | Female | No | Hypertrophic LP | Pembrolizumab | lung adenocarcinoma | 6 months | Topical steroids Systemic steroids Hydroxychloroquine |

| Economopoulou et al., 2020 [9] | 66 | Male | Yes | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Nivolumab | metastatic oral cavity cancer | 8 months | Topical steroids |

| De Lorenzi et al., 2020 [8] | 68 | Male | No | Bullous LP | Nivolumab | Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma | 3 months | Systemic steroids Withdrawal of ICIs |

| Yilmaz et al., 2020 [10] | 27 | Female | No | Classic cutaneous LP | Nivolumab | Metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma | 5 months | Topical steroids |

| Ferguson et al., 2020 [11] | 73 | Female | Unspecified | Classic cutaneo-mucosal LP | Nivolumab | Metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma | 18 months | Topical steroids Betamethasone mouthwashes Systemic steroids Withdrawal of ICIs |

| Uthayakumar et al., 2021 [14] | 62 | Female | Unspecified | LP pilaris + Classic cutaneous LP | Pembrolizumab | Metastatic melanoma | 9 months | Topical steroids Topical tacrolimus Doxycycline 100 mg: Initially slowed the progression Hydroxychloroquine Systemic steroids |

| Hanamie et al., 2022 [12] | 74 | Female | Unspecified | Classic cutaneous LP | Nivolumab | Non small cell lung cancer | 6 weeks | Topical steroids |

| 81 | Male | Unspecified | Bullous LP | Pembrolizumab | Non small cell lung cancer | 6 months | Topical steroids Oral antihistamine | |

| Our case | 60 | Male | No | Classic cutaneous LP | Pembrolizumab | Pulmonary giant cell carcinoma | 7 months | Topical steroids Withdrawal of ICIs |

Acknowledgments: Dorsaf Elinkichari is the guarantor of the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. Juliet Tantot contributed to acquisition of data, and interpretation of information. Stéphane Dalle revised data critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Informed consent: The patient has given informed consent to the publication of his case details.

Funding: None

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest to disclose

References

- Martins F, Sykiotis GP, Maillard M, Fraga M, Ribi C, et al. (2019) New therapeutic perspectives to manage refractory immune checkpoint-related toxicities. Lancet Oncol. 20(1): e54‑64. [PubMed.]

- Boussiotis VA. (2016) Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N Engl J Med. 375(18): 1767‑1778. [PubMed.]

- Apalla Z, Nikolaou V, Fattore D, Fabbrocini G, Freites-Martinez A, et al. (2022) European recommendations for management of immune checkpoint inhibitors-derived dermatologic adverse events. The EADV task force « Dermatology for cancer patients » position statement. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 36(3): 332‑350. [PubMed.]

- Weston G, Payette M. (2015) Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 1(3): 140‑149. [Ref.]

- Le TK, Kaul S, Cappelli LC, Naidoo J, Semenov YR, et al. (2022) Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: incidence and types of reactive dermatoses. J Dermatol Treat. 33(3): 1691‑1695. [PubMed.]

- Schaberg KB, Novoa RA, Wakelee HA, Kim J, Cheung C, et al. (2016) Immunohistochemical analysis of lichenoid reactions in patients treated with anti-PD-L1 and anti-PD-1 therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 43(4): 339‑346. [Ref.]

- Madan V, Marchitto MC, Sunshine JC. (2023) Pembrolizumab-Induced Lichen Planus Pemphigoides in a Patient with Metastatic Adrenocortical Cancer: A Case Report and Literature Review. Dermatopathology. 10(3): 244‑258. [PubMed.]

- de Lorenzi C, André R, Vuilleumier A, Kaya G, Abosaleh M. (2020) Bullous lichen planus and anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy: Case report and literature review. Ann Dermatol Vénéréologie. 147(3): 221‑227. [PubMed.]

- Kennedy S, Hall PM, Seymour AE, Hague WM. (1994) Transient diabetes insipidus and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 101: 387-391. [PubMed.]

- Jard S. (1983) Vasopressin: mechanisms of receptor activation. Prog Brain Res. 60: 383-394. [PubMed.]

- Hughes JM, Barron WM, Vance ML. (1989) Recurrent diabetes insipidus associated with pregnancy: pathophysiology and therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 73: 462-464. [PubMed.]

- Hamai Y, Fujii T, Nishina H, Kozuma S, Yoshikawa H, et al. (1997) Differential clinical courses of pregnancies complicated by diabetes insipidus which does, or does not, pre-date the pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 12: 1816-1818. [PubMed.]

- Gordge MP, Williams DJ, Huggett NJ, Payne NN, Neild GH. (1995) Loss of biological activity of arginine vasopressin during its degradation by vasopressinase from pregnancy serum. Clin Endocrinol. (Oxf). 42: 51-58. [PubMed.]

- Benchetrit S, Korzets Z. (2007) Transient diabetes insipidus of pregnancy and its relationship to preeclamptic toxemia. Isr Med Assoc J. 9: 823-824. [PubMed.]

- Iwasaki Y, Oiso Y, Kondo K, et al. (1991) Aggravation of subclinical diabetes insipidus during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 324: 522-526. [PubMed.]

- Ray JG. (1998) DDAVP use during pregnancy: an analysis of its safety for mother and child. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 53: 450-455. [PubMed.]

- Aleksandrov N, Audibert F, Bedard MJ, Mahone M, Goffinet F, et al. (2010) Gestational diabetes insipidus: a review of an underdiagnosed condition. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 32: 225-231. [PubMed.]

- Kalelioglu I, Kubat Uzum A, Yildirim A, Ozkan T, Gungor F, et al. (2007) Transient gestational diabetes insipidus diagnosed in successive pregnancies: review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and management of delivery. Pituitary. 10: 87-93. [PubMed.]

- Brewster UC, Hayslett JP. (2005) Diabetes insipidus in the third trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 105: 1173-1176. [PubMed.]

- Sherer DM, Cutler J, Santoso P, Angus S, Abulafia O. (2003) Severe hypernatremia after cesarean delivery secondary to transient diabetes insipidus of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 102: 1166-1168. [PubMed.]